35 Years Ago, This Dark Gen-X Classic Helped Bring Anime To America

Do your kids love anime? Do you love anime? Thank Akira.

Three decades ago, children could not watch anime shows on TV as easily as today, and there were few adults checking them out either. If you grew up in the ’70s, you could turn your dial after school and watch shows like Star Blazers, or Battle of the Planets, but these were for young kids, with brightly colored superheroes or smiling giant robots winning the day. So, other than Astro Boy and Voltron, how did anime crack America in the late 1980s? The answer is somewhat surprising: A very dark, brooding cyberpunk movie helped kick off the anime boom in the U.S. The movie was Akira and was first released on July 16, 1988, in Japan, before making its way over to America.

The movie showed up when Generation X was beginning to make their voices heard, allowing for Akira to be the perfectly-timed and unusual companion for that movement, and the masterpiece is more than a little responsible for helping make anime mainstream for the cool kids.

Ground-breaking is not just the word to describe Akira. It’s also the way the movie opens. On July 16, 1988, this post-apocalyptic cyber-punk masterpiece premiered in Japanese theaters, and not long after, inside American VCRs. Few were ready for this shocking animated film starring teenage biker gangs, ageless kids with wild psychic powers, and nightmarish cyber-organic abominations. Then, when you mix in gorgeous animation with counter-culture, mind-altering pharmaceuticals, and a heaping dash of gore, Akira stunned audiences on arrival at breakneck speed.

Inspired by Blade Runner, Star Wars, and European comic artist Moebius, Akira began as a manga by Katsuhiro Otomo in 1982. Otomo’s love of American movies wasn’t limited to just dark sci-fi, as he was drawn to outsiders on the fringes of society, like in Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy. The unusual story paired with Otomo’s meticulous illustrations made the comic an instant success, and it wasn’t long before he was courted to turn the manga into a movie.

Confounded by the archetypes of his genre, Otomo sought to make Akira stand out against an oversaturated landscape by featuring disillusioned young adults looking for a purpose in a world that doesn’t make sense. Kaneda is like Marlon Brando from The Wild One, rebelling for the sake of being a rebel. Kei fights in the underground against a corrupt regime, alongside a people’s youth movement. Tetsuo leads an aimless life with no purpose, perpetually seeking his purpose through the film, only to realize he’s sabotaged himself from ever finding that.

Everything about the making of the movie Akira was unconventional, but the results speak volumes. Otomo insisted on total creative control, including storyboarding the entire film singlehandedly, a feat recently made available to the public. Doing this allowed him to edit the movie before it was animated, ensuring tight storytelling from a very early stage.

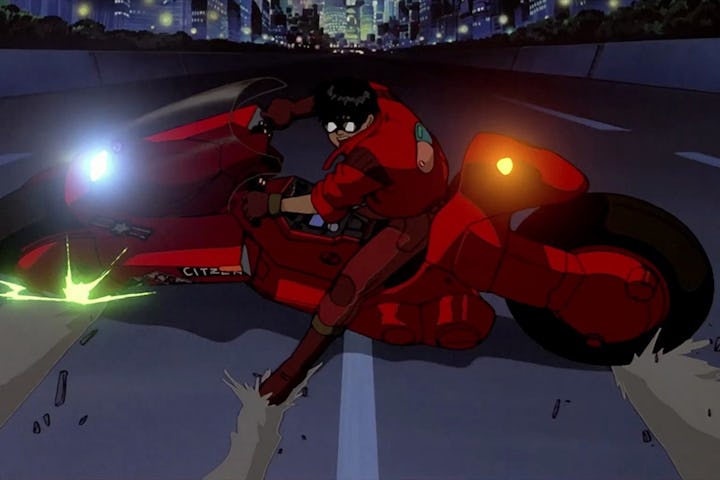

What everyone remembers first when you mention Akira is the motorcycle chase that starts the film. It sets the tone, with the lavish details of dystopic Neo-Tokyo, the unrest of its resident youth, and a society tearing itself apart. It’s also a showcase for state-of-the-art visuals, from the unnatural neon glow of the consumerist cityscape to the light trails beaming from the speeding bikes as the battle between Kaneda’s gang and the Clowns takes place. This appetizer is a taste of what’s to come and a pivotal reason behind Akira’s success and longevity.

What makes Akira so great to this day is that fluid animation, and even now, few modern anime rival the smooth flow of this beauty. This was thanks to Akira’s production budget, weighing in at an astronomical $10 million USD, an amount unheard of at the time. Over 160,000 hand-drawn animation cels constructed the two-hour runtime, double the average animated film. While still a developing art form, CGI was also utilized in a handful of scenes that wowed audiences when they first saw them.

The animators were given pre-recorded dialogue to work from, atypical of the usual workflow of the time. Akira’s team matched the actor’s lip sync but had the freedom to draw the characters as dynamically as they dreamed. Likewise, the voiceover actors weren’t tethered to pre-drawn work and could develop the characters for themselves. Every aspect of Akira was intended to be unique, cinematic, and disruptive to audiences’ expectations.

Akira’s entry into America couldn’t have come at a better time. Years before the anime was released, the manga reached US shores in 1988 thanks to Marvel Comics. That’s right, the folks behind Spider-Man and The X-Men were the first to put their support behind Akira. The movie had a brief run in US theaters in ’89, but its arrival on VHS was how it truly gained popularity. The first dub came to home video in 1991, and its reputation made it a hot item for tape traders. Back then, VHS was the only way to find adult-oriented anime, and Akira was the one everyone had to see.

Looking at the pop-culture timeline, Akira landed in the most opportune spot possible. This was the era of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight and other mature comics intended for comic readers who aged up, up, and away from spandex-clad superheroes. 1991 was also the same year Nirvana’s Nevermind hit, heralding the grunge era for mainstream music. It’s easy to imagine the soundtrack for Akira featuring some sickAlice in Chains or Pearl Jam tunes! (It doesn’t, but it makes sense, right?) The nihilistic story of Akira was a perfect fit for this period, blending sci-fi and genre-bending art against themes of alienation, social introspection, and the search for meaning while living in a world where everything feels futile.

The influence of Akira is limitless decades later, with The Matrix and Stranger Things taking pointers from the anime. Guillermo del Toro loves the film and has counted it as an inspiration for his work. South Park’s “Trapper Keeper” episode famously parodied the finale of the film and even Kanye West’s “Stronger” music video. Simpsons and comic book fans need to know about Bartkira, a prolific parody of the manga told through The Simpsons, starring Milhouse as Tetsuo.

Beyond parody, countless films, tv shows, and cartoons in both the US and Japan paid homage to Akira through “The Akira Slide.” That famous scene from the motorcycle chase where Kaneda skids to a halt on his futuristic motorcycle has been redone in places like Adventure Time, TMNT, Star Wars cartoons, Yugi-Oh, Steven Universe, and most recently in Jordan Peele’s Nope. Even Pokemon has done it!

Manga had been on the verge of breaking through to American audiences at the start of the 90s, upping the ante with mature themes, along with a shocking dose of nudity and super adult themes. Akira pushed it over the edge, paving the way for Ghost in The Shell and Neon Genesis Evangelion, among others. Its connection to the state of pop culture at the time it arrived in America is often overlooked, but it truly is the anime anthem of Generation X. The anime king of the forgotten VHS days, Akira left an impact 35 years ago that every great anime thereafter bows its head to. It’s obviously not one you’re gonna show to your young kids, but a lot of the anime they love was certainly helped along by this movie, and the generation who embraced it.

Akira is streaming on Hulu and Crunchyroll, or you can buy it on Blu-Ray or DVD from Amazon.

This article was originally published on