40 Years Ago, The Critics Hated Jim Henson’s Dark Crystal. They Were Wrong

Children's cinema has rarely been braver or more artful than The Dark Crystal.

Today, Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal is widely considered a masterpiece. It’s easily one of the best kids’ movies of all time, even if it scared the hell out of kids forty years ago. But, back on December 17, 1982, when Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal arrived in movie theaters throughout the United States, the critics were not happy. Like most groundbreaking creative projects, most of the critics didn’t quite get it. And the early reviews were truly savage.

Vincent Canby of the New York Times filed a negative review, declaring the film uninteresting and “without charm,” while Rex Reed of the New York Post not only took issue with the film’s price tag(“It seems almost obscene to spend $26 million on a movie for children”) but also its characters and tone (“the monsters and bizarre creatures…are so horrifying they just might give impressionable tots nightmares for days.”)

But perhaps the most sardonic — and telling — review came from Richard Corliss of Time. “No Kermit. No Bert and Ernie. Sam the Nixonian Eagle and Grover, with his perpetually pubescent voice, are elsewhere,” he wrote. “This movie is serious: Jim Henson’s foray into the art, dammit, of puppetry.”

Despite his dismissive tone, Corliss was right on several fronts. The Muppets, Henson’s felt and foam creations with lovably imperfect personalities—the ones that had recently taken over primetime television for five seasons and profitably adorned the silver screen in two feature films—were nowhere to be found in Thra, the spiritual world that houses Dark Crystal’s unearthly inhabitants like the humane Gelfling, the insidious and vicious Skeksis, and their counterparts, the wise and patient Mystics.

And yes, while The Dark Crystal was ostensibly made for children—although Henson and Brian Froud, the English artist who used his unique sensibility and creativity to cocreate and conceptualize Thra and its many inhabitants, would likely disagree with that supposition—it was a project that the entire creative team took very seriously.

And what a creative team it was! The film was only the second time Jim Henson sat in the director’s chair on a feature film (the first being The Great Muppet Caper, a film he agreed to do only if he could also secure financing for Crystal, his longstanding dream project). Frank Oz, his longtime collaborator, accepted his friend’s invitation to codirect. Puppet designer Wendy Midener met her future husband while working on the film—her last name was changed to Froud by 1980—and took a brief hiatus from working on Crystal’s Gelflings to lend her expertise to The Empire Strikes Back, fabricating a brand-new character for the Star Wars universe: Yoda.

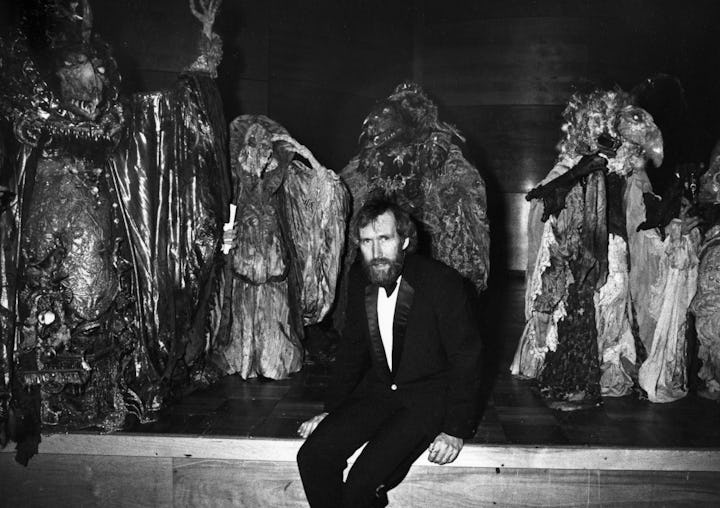

The Skeksis in The Dark Crystal.

While The Dark Crystal’s story is beautiful in its simplicity—a majestic tale of an adolescent on a quest to fulfill an ancient prophecy and restore balance to a broken world where evil has overcome good—what stands out as the film’s crowning achievement is, of course, the puppetry.

Forty years after the film first arrived in theaters—it briefly enjoyed a Fathom Events re-release this month for its Ruby Anniversary—the movie somehow seems even more groundbreaking and breathtaking than it did in the Eighties. In an industry where “one of a kind” is an overused and often hyperbolic honorific, The Dark Crystal is the rare gem that truly deserves the title. After four decades, it remains the only live-action film to not include a single human character or actor, as Jim Henson and his collaborators created an entire world populated with otherworldly creatures, realized on screen entirely with puppets.

To remix a phrase from Richard Corliss’s review in Time, puppetry is art, dammit. It’s impossible to overstate the importance and cultural impact of the Muppets, The Dark Crystal marks a crowning achievement not only in Jim Henson’s career but also his preferred medium. In many ways, although he had accomplished much over his thirty-six years in the entertainment industry before his death in 1990, The Dark Crystal is his masterpiece. Not only was the film deeply personal for him—its plot was inspired by new-age spiritual philosophies that interested Henson at the time—but it also pushed the bounds of physical performance and technology to create puppets unlike anything audiences had ever seen before.

As Kathryn Mullen, who puppeteered Kira in the film, observed when I spoke to her for my book, The Dark Crystal: The Ultimate Visual History, “Jim had a great respect for the art form of puppetry. Every artist wants to explore life’s mysteries. That’s what artists do, and puppets were Jim’s medium. Questions about whether The Dark Crystal was perfect or not miss the point. Artists don’t strive for perfection; they strive to reach the depth of human feeling and emotion. He had the opportunity to do that and he grabbed it, because, above all else, Jim Henson was an artist.”

However, despite Jim Henson’s artistry, in 1982, it seemed the critics were right. The film ultimately turned a small profit, but with its sizable budget, its $40.5 million box office return was considered a significant disappointment. Henson and Brian Froud joined forces again on 1986’s Labyrinth, another fantasy cut from the “Brothers Grimm meets J. R. R. Tolkien” mold—except this time with human characters, musical numbers, and more overt humor for good measure—yet that film failed to resonate with audiences too. Labyrinth only earned $12.7 million domestically in its initial theatrical run.

For Jim Henson, who wanted to avoid being stereotyped as “the Muppet guy” and had other stories inside of him that he wanted to share, the dual disappointments of The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth were hard pills to swallow.

“I remember later in his life, a while after Labyrinth was released, there was an encyclopedia of film directors that came out,” his daughter Cheryl Henson told me for The Ultimate Visual History. “We were thumbing through it, and there were hundreds and hundreds of film directors, but he was not listed. I know that sounds kind of petty, like, ‘why would he care? He was so famous with other things,’ but he wanted to be acknowledged. I can’t say he was completely over it. He had spent eight years of his life working as a film director, and was never really recognized within the industry as one.”

Ultimately, Jim Henson never directed another feature film again.

But just as things move slowly on Thra, it would take a while for things to happen when it came to The Dark Crystal. It took Jim Henson seven years to bring The Dark Crystal to the big screen—amazingly, the creature design and worldbuilding were underway long before there was a script—and several decades before the film would be widely appreciated for the spectacular it is. The ninety-three-minute film has grown into a bonafide franchise, with merchandise, a stellar novelization series by J.M. Lee, and an Emmy Award-winning (and frustratingly short-lived) series, The Dark Crystal: The Age of Resistance, on Netflix.

The Dark Crystal (1982).

The movie remains the ultimate testament to creativity and collaboration, and while Jim Henson didn’t live long enough to see popular opinion turn The Dark Crystal’s favor, he had the satisfaction of knowing that, dammit, he had made a feature film that was pretty significant.

“I like to think of Dark Crystal as…a work of art, but it’s not a personal work of art. It’s not just something I did,” Jim Henson said. “Frank and Brian, and [producer] Gary [Kurtz], and all the performers—hundreds of people—created this thing and, as a work, I think it’s something we’ll always be happy with. All in all, we spent over five years working on the film. It’s probably the hardest thing that I’ve ever worked on. It was the most work. It was the most difficult, but it was the most fun. It was the most rewarding and, of all the projects that I’ve ever worked on, it's the one that I’m most proud of.”

The Dark Crystal is currently streaming on Paramount+.

Get a signed copy of The Dark Crystal: The Ultimate Visual History right here.

This article was originally published on