Is ‘Joker’ a Good Movie? Yes, But in a Cringe-y Way.

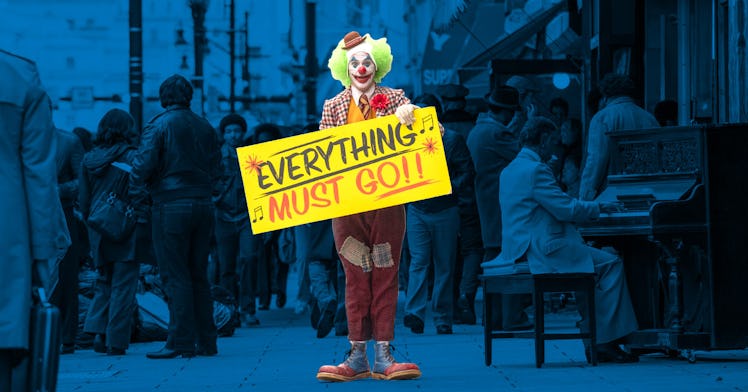

Joaquin Phoenix delivers big time in the Todd Philips auteur-turn that no one really needed.

Joker is a cinematic troll job, albeit a masterfully sculpted one. Though more complex than the straight-to-4Chan reputation that has already preceded the film, Joker is a remarkable piece of movie-making mostly in the sense that Todd Philips and Executive Producer Bradley Cooper got it made. What was the elevator pitch? It’s Inside Llewellyn Davis, but this time he kills the cat and beats Dylan with a guitar? The film is a joyless all-you-can-eat buffet of mustard greens that will take coitus off the table half an hour into date night.

Does Joaquin Phoenix deserve an Oscar? Let’s get it out of the way and acknowledge that he does. But let’s also agree to give it to him at a private ceremony. We can’t encourage this kind of thing.

Phoenix’s performance, all chitinous lurches and fencing responses, is tour-de-force Sam-Waterston-screaming-Hamlet-in-Central Park stuff that does the impossible by making Jared Leto’s turn in the faceprint look worse in retrospect. But what is excellence in service of a bad idea? Remember when Herschel Walker, the best running back on the planet, played for the New Jersey Generals of the USFL? You don’t see those jerseys much anymore. Phoenix’s heel turn — consisting largely of heal turns — will be similarly lost in the archives. Maybe they’ll make a 30 for 30 about it. Maybe they should.

The question becomes whether the movie is worth the performance. Yes, but not definitively.

On a scene-by-scene basis, Joker delivers in the extreme. At one point, Arthur Fleck, our clown has a nom-de-paix in this one, covered in blood and spots-be-damned, politely thanks the one character in the film who has been kind to him, a man suddenly extremely conscious of his carotid artery. It’s the sweetest moment of the film and almost physically jarring because this sudden sentimentality makes matters worse. Arthur Fleck is not — let’s borrow a term here — “werewolfing.” He’s human and monstrous all at once. Joaquin Phoenix can multitask, to put it extremely mildly.

Warner Bros

The core issue is that the film is animated by a hypothesis it eventually proves to be wrong, namely that the Joker can carry a movie and, more critically, that he should. Much will be made of the morality of depicting a lonely white man becoming a shooter then glorifying that pilgrim’s progress. (Philips doesn’t make it look glorious, but on a big enough screen, everything is romantic. Right?) The film is decidedly not an incel call to arms but can be willfully misread as such and is verite enough that Gotham winds up in the same reality as Aurora. So the Twitter vitriol shouldn’t be dismissed. But, offline the issue from a viewer’s standpoint is incoherence. Joker is a logical movie about illogic and there’s something fundamentally disturbing about that.

What made Heath Ledger, who gets the homage he deserves here, so singularly terrifying in this role was his refusal to disclose motivation. In contrast, Joker reads like a list of motives. It feels more like a gritty reboot of Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day than the Batman franchise. Provide chaotic evil with a character arc and a sympathetic backstory is like hitting a magnet with a hammer. The Joker remains scary, sure, but he loses his sticky quality.

Unlike love, suffering is not inherently interesting.

The problem here isn’t so much that this movie glorifies a bad guy or justifies his actions, but that it’s structured around the idea that long-suffering Arthur Fleck must have something to say. “The problem with being mentally ill is that everyone expects you to act like you’re not,” he scribbles in his journal in an early scene. That expectation seems to be shared by the filmmakers, who want him to stand for something or, as it happens, nothing. “I don’t believe in anything,” says Joker. But that’s disingenuous. He believes in the primacy of his own experience and significance of his own humiliation. It’s not so much that he wants to watch the world burn. He wants an apology. He’s just willing to settle the flames. It’s all a bit small.

Not that he doesn’t deserve an apology. The movie opens with him getting assaulted by two gangs, one poor and one rich. In both instances, he’s done nothing to antagonize his attackers but exist. That existence is treated as an affront. Violence ensues. But here’s the thing: It’s not as random and “crazy” as Arthur Fleck might like to believe. There is something viscerally provocative about the character. His presence is an affront, a reminder to everyone who sees him that, in a fractured, unempathetic society, utter dissolution is just a bit of bad luck away. We punch what scares us.

To be fair to Philips and Silver, who co-wrote this as penance for 2009’s X-Men Origins: Wolverine, they seem to be in the know. The filmmakers wink at the weaknesses, in their own story, but don’t dwell. They are too busy doing filmmaking. The movie is, as has been observed elsewhere, a fairly straightforward bit of Scorcese-humping. That’s not a bad thing in and of itself, but Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy were contiguous with the world into which they were projected. Joker isn’t. Populism, in this film, is a product of inequality. Plutocrats sneer at the ill-informed rather than spoonfeeding them their own regurgitated resentments. The titular mass shooter demands a stronger social safety net.

The film takes place in 1981 (witness the Zorro: The Gay Blade movie marquee) and is populated by characters obsessed with city government precisely because Philips and Silver intend to straight-arm political reality. Again, this is fine so long as there’s no expectation of profundity. The movie looks like a thinker and feels like a thinker, but doesn’t hold up particularly in the face of thought.

Still, Joaquin.

The thrill of Joker is the thrill of watching someone be really good at their job. It’s no secret that Joaquin is a stellar actor and he already delivered a more muted version of this performance in You Were Never Really Here, but he really lets this thing rip. His ribcage (this is not a metaphor) should get second billing. His shoulder blades should get a producer credit. His slightly too small lateral incisor steals a scene.

Phoenix’s work here is so prodigious that it will drive interest in Joker — as well it should — and imbue the film with real significance — as well it shouldn’t. Because, ultimately, this is just another comic book movie for adults. It is masterfully crafted, sure, but it’s still a pinch-pot ashtray. You wouldn’t want to eat out of it.

This should go without saying, but don’t take kids to this movie. If you have teenagers, don’t take them either. Their extremely online friend will do it for you.

Joker is expected to be released in theaters on Friday, October 4, 2019.