25 Years Ago, The Original Alt-Rock Band Rebooted With A Forgotten, Misunderstood Album

Let’s get into the highs and lows of Up.

Twenty-five years ago, on October 26, 1998, R.E.M. released Up, their first record without founding member Bill Berry. He’s left the band after the curious one-two punch of suffering a brain aneurysm on tour and the band pulling an $80 million record deal, the biggest ever at that point. If Berry was part of R.E.M.’s secret sauce, it wasn’t really apparent until after he left. And, when you look back at 1998’s Up, it reveals a good deal about just how rocked Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Mike Mills were by Berry’s absence.

But, crucially, this album also demonstrates how they fully embraced trying to answer the question of who R.E.M. would be going forward. Whether you’ve forgotten about this record, or never even heard it, Up is a strange and oddly-affecting album well worth visiting with. Because R.E.M. was, in many ways one of the first true alternative rock bands, this moment of reinvention was a bigger deal than you might remember.

I came to R.E.M. late. In the summer of 1994, my parents rented a room to an apprentice carpenter from our church who traveled with a suitcase of dubbed tapes. His copies of Reckoning and Dead Letter Office with their collaged cassette J-sleeves (which I totally didn’t steal). But I caught the bug hard. Later, in 2000, I was making my college roommate’s detour from a spring break trip to West Palm Beach to visit Weaver D’s Delicious Fine Foods in Athen, GA because the hole-in-the-wall soul food restaurant had lent R.E.M. it’s slogan of Automatic for the People. (Dusk, the place was closing when we pulled up in my dad’s 1987 Suburban, but proprietor Weaver D took pity and cooked us a meal, though had us clean the collards.)

And so, understand, that in 1997, I was hit way harder than was reasonable when Berry announced his retirement: like, I was family-cat-dying level sad.

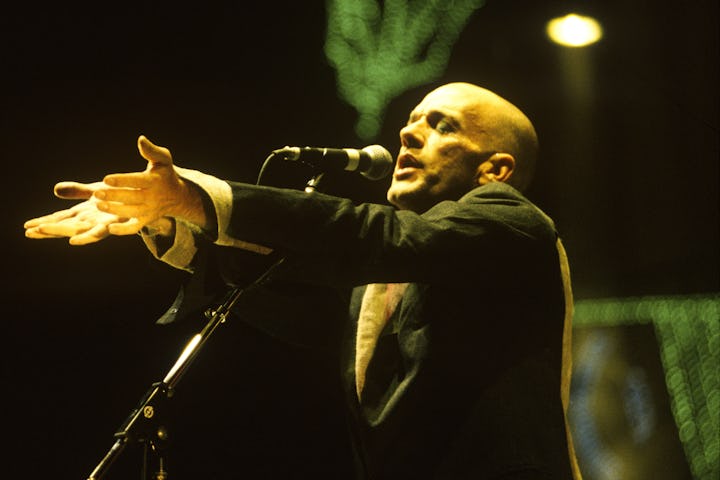

R.E.M. in 1995. From left to right: Bill Berry, Peter Buck, Michael Stipe and Mike Mills.

Up was the first record that I actively wanted to love. Even before buying the CD at In Your Ear, and pressing play, there were some serious stakes. I knew it was gonna be hard to keep loving this band. And let’s be honest: Up is a weird record. And it’s weird, unlike R.E.M.’s previous incarnations of weird. There’s barely a hint of the species of rock the band had conquered the “alternative” scene within the 90s: none mandolins, and none jangly Rickenbacker 360 arpeggios. Rather, the band seems to have stolen a bunch of someone else’s synthesizers and samplers and said “Okay, let’s start over.”

The album’s opening track, “Airportman,” baldly acknowledges something changed. A drum machine, which R.E.M. had rarely ever messed with, anchors this weird little synth-rich number with Peter Buck’s wailing ebow, Stipe’s near whisper, and Mill’s buried piano the only hints that this still might be, maybe, R.E.M. Embracing the drum machine is a very deliberate decision after losing their drummer and specifically stating they wouldn’t replace him. While their use of the instrument mixed at best (no one in the band reveals himself to be a closet beatmaker a la J Dilla or Timbaland), the edge of electronica marks these songs as new territory.

But R.E.M. knew they had a rep as stadium rockers–and were operating with very real pressures and expectations. Track 2 comes in hard with the obviously human drummer (journeyman Joey Waronker, thieved from Beck): “Lotus” is the closest thing to a recognizable “alternative rock” song that Up gets. While the song remains oddly catchy and singalong-able (“haven’t you noticed / I ate the lotus”) and features solidly Peter Buck guitar licks, it still feels the most try-hard of this new batch of songs (something I felt watching the band play the song on Late Night with Conan O’Brien in November 98 in my college common room). The song seems the clearest nod to the band’s awareness that Up was the first record they were making under their new $80 million Warner Brothers contract–then, the largest ever, deal, outpacing Metallica’s $60 million with Elektra and Janet Jackson’s $70 million with Virgin. With or without Berry, they couldn’t really make a “small” record.

The best songs on Up are probably those that thread that needle between Berry’s felt absence and the band’s embrace of a different kind of song. “At My Most Beautiful” (a Beach Boys-esque number), the midtempo ballad of “Sad Professor,” and the acoustic-driven single “Daysleeper,” are all really wonderful songs. My favorite album track is the weird electronics-heavy “Hope,” a song that seems to be about someone’s fear of undergoing experimental surgery. Singer and lyricist Michael Stipe realized he’s ripped off (kinda, sorta, maybe?) the melody from Leonard Cohen’s 1969 “Suzanne,” so the band credits Cohen as co-songwriter on this strange song that accumulates frenzied layers of synths and beats. The song still gives me chills for reasons I don’t quite understand. But I guess that’s the magic of R.E.M. right there.

R.E.M. in 1995.

Up’s low points (see what I did there?)—which are still perfectly listenable—are tracks that, I’m not sure how to say it, exist in a kind of netherworld between pop, rock, electronica, and something properly experimental. But “The Apologist” and “Falls to Climb” aren’t defining, blossoming in-betweenness, but feel more like a stuckness, a sort of holding pattern to see what might come next. Suggesting R.E.M. was thinking: we know we’re not what we were with Bill Berry, but we’re not really sure what the three of us are yet—we’re figuring it out, and we’re sharing this figuring with you. Which is cool.

Up is maybe best seen as an experience of the artistic process —and an honest and generous one. Twenty-five years on, Up is one of R.E.M.’s more forgotten records. It’s neither the college-radio punk-adjacency of their early stuff like Murmur (1982), nor the pop peaks they reached in their middle heyday of Out of Time’s unlikely mandolin-driven, #4 Billboard hit “Losing My Religion” or Automatic for the People’s “Everybody Hurts” and “Man on the Moon.” But it’s also not remembered, like 2004’s Around the Sun and 2008’s Accelerate, as mostly fizzle and disappointment–albums that feel (then and now) like unfortunate amalgams of tired creativity and the need to fulfill a record contract.

So track down Up on your favorite streamer, or grab yourself a pre-order copy of the re-mastered re-released vinyl (out in November). Lose yourself among “At My Most Beautiful” sleighbells, organs, and harmonies, or try to understand why you’re crying inside Hope’s lyrics: “And you want to go forever / And you want to cross your DNA / To cross your DNA with something reptile / And you're questioning the sciences / And questioning religion / You're looking like an idiot / And you no longer care.” Or fall in love again with “Why Not Smile,” even if you can’t figure out why they didn’t include the beautiful Oxford American version that could only be found for a long time on a CD that accompanied an obscure literary magazine. As a trio, R.E.M. had become a different beast: but Up shows that they could still work some magic between them.

This article was originally published on