75 Years Ago, One Kids’ Book Pushed The Boundaries Of Children’s Literature

Picture books have never been the same since The Important Book. And that’s a good thing.

Nearly every parent is familiar with Goodnight Moon, the most iconic children’s bedtime story for over seven decades. Considered simply the best tale to read before sending your young ones to sleep, this classic overshadows the extensive catalog of wonderful kids’ books Margaret Wise Brown wrote during her prolific lifetime (and many published posthumously). One of those entries arrived 75 years ago when The Important Book was published in 1949. Never heard of it? Well, it’s a 24-page avant-garde picture book that critics continue to label as Brown’s best work. And with good reason.

While the series of poems can be read in a few minutes by the average adult, the deeper meaning is found in the spaces between them. This meditation on existence is a reminder that children’s storybooks are an art form unto themselves, while also being an open window into the mind of one of the most fascinating authors of her time who revolutionized what kids read. For a thin book of one dozen poems without rhyme to be presumptuously titled The Important Book requires serious fortitude, and diving into it today proves why this short evocative read is even more powerful now as an adult than it was as a child.

What’s The Important Book About?

The Important Book read aloud by “Story Time with Bizzy Book Club”

The Important Book is a series of short poems with seemingly no overt narrative or connection to each other beyond the staples binding the paper together. Every two-page spread explains matter-of-factly what a particular thing is, ranging from man-made objects to elements found in and of nature. Eleven passages constitute the entire affair, including a semi-hidden poem found on the opening page about crickets.

Brown declares in the simplest of ways what is important about glass, spoons, grass, snow, wind, shoes, and more with the authority of a child who knows more about the world than you. It professes intrinsic expertise over the subject matter, but not scientific so much as tactile and sentimental. For example: the lines that read: “The Important thing/About grass is that it is green.”

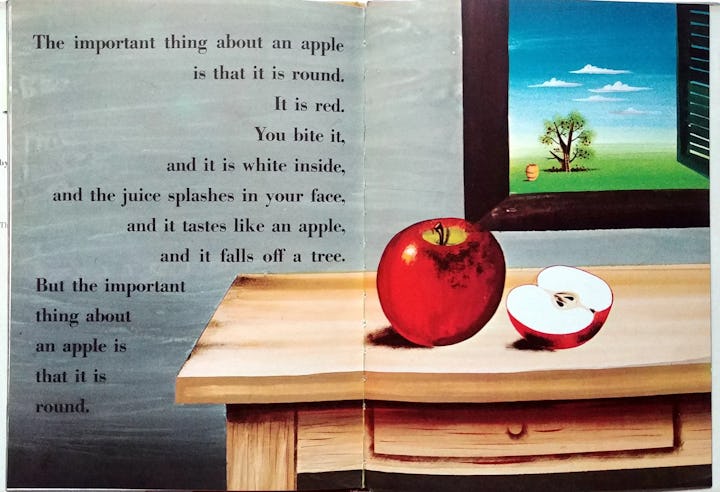

Rain “sounds like rain,” spoons are used to “spoon things up,” and apples taste like apples. It’s shocking to realize how descriptive these passages are, profound from the perspective of an adult, and innocently natural to the way a child interprets their surroundings. There’s a naivete to the language, yet these simple summaries create perfect visualizations of a personal experience rather than what the story dictates you should think about. Brown doesn’t clutter the reader with fancy wordplay, but wants them to open their minds to their own memories that each page brings them.

Any rhyming is unintentional, as Brown follows the beat of her own drum. There’s no discernible pattern to these makeshift monologues, although the writing has a dream-like lyrical quality to it that transforms it from a long sentence into something poetic.

Brown was a lover of modern art and employed illustrators with a contemporary aesthetic of bold colors and impactful design instead of the placid monochromatic drawings typically seen in storybooks from this period. Leonard Weisgard painted this book, their fourth of six partnerships together. Each image is vivid and bright, stark in their immediacy. My personal favorite is the page for snow, which features a wintry scene of children playing outside their homes in the distance, while a bird peeks toward the reader perched on the bare skeleton of a leafless tree in the foreground. The Caldecott award-winner shared Brown’s view on the “strawberries and cream” concepts prevalent in children’s books and joined her on several focus group sessions with her classes to test their work.

What Makes The Important Book So Special?

“The important thing about snow is that it is white.”

Brown described her work as “word patterns” or “interludes,” and that perfectly summarizes the feel of The Important Book.

Repetition is a major element in The Important Book, whether it be using the word being discussed as a descriptor, or repetition of repeating the opening line of each section at the end. This emphasizes “the important thing,” which is the most immediate aspect of these things, treating them more abstractly than just a thing. Brown expands upon it in each verse, but that initial reaction and discovery remain in focus. She puts words to intangible elements, things that are obvious yet unspoken.

Returning to Mitchell’s concept of “here and now,” The Important Book is unpretentious in its exploration of what children may experience on an everyday basis. It lacks contractions (one homage of several in this book to one of Brown’s favorite writers, Gertrude Stein), pacing itself comfortably with its gentle stream of consciousness. It’s not trying to teach a vocabulary word or anything substantially educative from a classroom, offering the audience an idea to take a moment outside of itself, calculated with zen-like precision of language. Even the typography plays alongside the illustration, making the text into an additional work of art with a dose of E.E. Cummings’ design.

The true message of this bestseller comes at the end, as the final poem tells the reader “the important thing about you.” The significance of this conclusion is a reminder of your personal growth, with the words taking note of your physical maturation from baby to child and eventual adulthood. Looking back on the way Brown transported the reader through these experiences, it suddenly becomes more personal, and each page suddenly has a deeper meaning, with your life experiences attached to every concept these poems touched on.

The Important Thing About You

In 1946, Life magazine wrote that people who didn’t understand the way Brown thought and spoke might liken her to “combine the best features of Dorothy Parker and Immanuel Kant,” intended as a mild insult but also an accurate observation. A forward-thinker who pushed the boundaries of the content inside picture books, too many people mistake Brown’s style as simple when nothing could be further from the truth.

Brown stripped away the unnecessary to write fiction that spoke the intimate language of her readers, and that’s why books like this remain so popular generations later. That radical approach allows space for the audience to nestle inside these books and make them a home of their own, inserting their core memories and experiences among Brown’s broad concepts.

A common high school or college graduation gift is Dr. Seuss’ Oh, the Places You’ll Go!, but The Important Book deserves a place among that memorable work, too. As an adult, The Important Book is not just a beautifully written and illustrated book, but it’s a way to remember milestones past as you realize all you’ve accomplished while growing up (no matter how old the reader may be). More importantly, it’s a reminder about finding the miraculous in the mundane. It’s more than taking these ordinary things for granted, but celebrating their unique functionality and role in the world, and an affirmation that You are You — and that’s the most important thing.