Gifted And Talented Students: Map Shows Bizarre State-To-State Distribution

Interestingly, there doesn’t appear to be any correlation between family structure and the number of gifted students in any given state. Ditto when it comes to education spending.

Some children are simply gifted. There is, perhaps, no rhyme or reason. There doesn’t appear to be any correlation between family structure and the number of gifted students in any given state. Ditto when it comes to education spending. Nearly 1 in 6 students in Maryland are formally recognized as gifted and talented—but the state ranks just about 25th in the nation when it comes to the percentage of children raised by both biological parents, and school spending per state GDP.

The upshot? Solid family structure and money—the two factors that influence almost every aspect of child development—do not seem to impact the number of gifted children in a state. So what does?

Roughly 3.2 million children are currently enrolled in gifted and talented programs in U.S. public schools. Still, the question of what exactly constitutes “gifted” lacks a clear answer. Federal law acknowledges that children with unique gifts may need unique attention, but stops short of providing guidelines for identifying such children. That’s usually handled at the local level, and processes vary widely from state to state. The National Association for Gifted Children considers a child gifted when, “compared to others his or her age or grade, a child has an advanced capacity to learn and apply what is learned in one or more subject areas, or in the performing or fine arts.” Still, that leaves plenty of wiggle room.

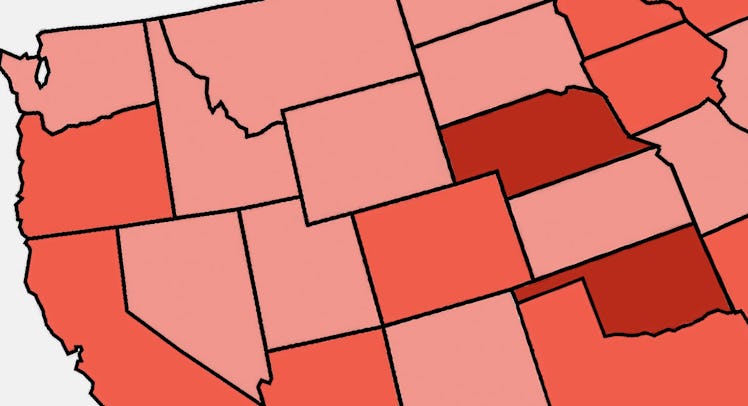

Subjectivity means that collecting data on “gifted” students is a daunting prospect. To figure out the percentage of gifted children in each state, we deferred to the National Center for Education Statistics. Maryland, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Indiana, South Carolina, Nebraska, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia all seem to believe that 10 percent of their students are “gifted.” Do these states have more children with an advanced capacity to learn? Nope. All this means is that these states have been most proactive about enrolling children in programs.

Now, two major factors that tend to influence student performance is education spending and family structure. Kids who are raised by married, biological parents tend to do better in school, and districts that spend the big bucks on education tend to see their efforts bear fruit. But when we ran figures from the Institute for Family Studies against the gifted data, we found no more gifted children in states that reported more married, biological parents raising those children. And when we ran data on the percent of a state’s GDP earmarked for education, we were similarly stumped.

As far as we can tell, these two variables do not impact enrollment in gifted and talented programs.

Confusing? Perhaps, but heartening as well. Our analysis drives home the point that gifted children come from all sorts of families, of all shapes and sizes, and that programs to help these children achieve their full potential need not cost state and local governments significant amounts of money.

“Gifted education services does not need to break the bank,” according to The National Association for Gifted Children. “Beginning a program requires little more than an acknowledgement by district and community personnel that gifted students need something different, a commitment to provide appropriate curriculum and instruction, and teacher training in identification and gifted education.”

This article was originally published on