Paternity Leave Helps Children By Promoting Coparenting

Paternity leave is a good start to fatherhood, but well-designed parental leave underpins the sharing of care that boosts early childhood development.

C. Philip Hwang is a professor of Psychology at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. His research focuses on child development, fatherhood, and the linkages between gender, family, and work in post-industrialized societies. He currently oversees the Gothenburg Longitudinal Developmental Study (GoLD), a 30-year prospective longitudinal study of Swedish families.

- Nationalized paternity leave policies in Sweden and other Nordic countries help men to advocate for their own leave at work.

- Support for working dads also represents support for working moms, who they are also looking to retain and reward.

- Research indicates that coparenting is vital to development and that coparenting is a skill that takes time to master.

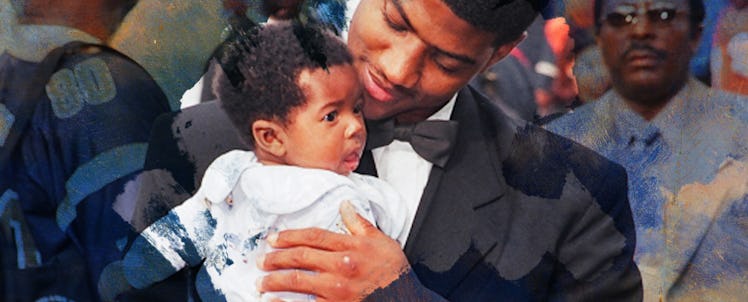

Children thrive when parents share their care. When dad is not only a source of parental love, but also a consistent presence, and a partner in the joint enterprise of parenthood, children benefit. But the participation of fathers in meaningful coparenting, arguably the most important role a paternal figure can take in terms of promoting early child development, is hardly a given. Men have not historically been encouraged to act as caregivers or to prioritize caregiving. This is why supports like paternity leave that facilitate fathers’ involvement and encourage him to become a competent and confident parent contribute so meaningfully to kids’ long-term wellbeing.

Unfortunately, American policy makers and human resource professionals have struggled to design leave arrangements that genuinely help fathers care for their children, particularly early on in those children’s lives. Schemes from around the world that were announced to great applause have often seen low uptake by fathers, who are — perhaps for cultural reasons and perhaps because they fear professional repercussions — often loath to take advantage of the offerings available to them.

The following originally appeared in a different format on the Child & Family Blog, transforming research on cognitive, social, and emotional development and family dynamics into policy and practice.

That said, pushes for paternity leave and gender equity in caregiving have not been uniformly unsuccessful. In Sweden and other Nordic countries, generous leave policies have met with success. These government policies address two powerful preconceptions about men, that they are indispensable as workers and entirely dispensable as caregivers.

The key to the Scandi success seems to be that benefits are dictated under national laws. That sends a loud signal. Once a set of behaviors becomes a legal expectation, it’s easier to justify on a personal level. It is also, and this is important to note, easier to rally behind in the workplace and at home. As the law created a space for men to be caregivers, men were more empowered to claim it as their own and women were more empowered to treat men as partners — with all the attendant expectations. Parental leave laws promote gender equity from two directions, positively incentivizing all parties.

Reserved time for fathers — “daddy months” as this has been dubbed — has much higher uptake. This “use it or lose it” parental leave, often staggered so it doesn’t coincide with mothers’ leave, empowers and almost forces to advocate for their own leave at work and at home and thereby challenges traditional attitudes in both locations. In Sweden, the introduction in 1995 of a “use-it-or-lose-it” daddy month led significantly more fathers to take parental leave. There was a further sharp increase in the number of days taken by fathers when a second “daddy month” was added in 2002. Now a third month has been added, and we are assessing the impact.

Other design features are also vital for successful uptake of parental leave by fathers — flexibility, large numbers of days available over a lengthy period, high levels of pay replacement and application to those working in the casual and self-employed labor markets.

Along with laws and social support, comes education. Employers in countries with codified protections and benefits for new parents are more educated on the business benefits that spring from supporting fathers. They understand that encouraging fathers to take leave will help long term with employee loyalty and retention. They also understand that support for working dads also represents support for working moms, who they are also looking to retain and reward.

Parental leave functions – for both men and women – by promoting continuous connection to both work and to children. It helps each parent to contribute to parental care and also access the earning and prestige that spring from participation in the labor market. However, the patchy success of parental leave legislation demonstrates that some key ingredients are required. A change in the law that simply allows fathers to take parental leave allocated on a family basis (so the mother effectively forfeits that time) works poorly and results in low paternal participation.

Private sector buy-in is critical, but it’s important to remember that the broadest social benefit of leave programs is the improved wellbeing of children. Fathers are, it’s worth stating clearly, important in early child development. Research does not suggest that fathers are intrinsically necessary for healthy child development and children can thrive without fathers or, for that matter, mothers. But research does indicate that coparenting is vital to development and that coparenting is a skill that takes time to master. By giving parents that time, employers and policymakers can provide clear developmental advantages for children and vital help to working caregivers.

This article was originally published on