The IQ Test For Kids That Never Caught On

An IQ test for babies might sound like an absurd gamble, but in 1986 Joseph Fagan III made a breakthrough that could "predict an infant's future intelligence." Luckily, it never caught on.

Measuring infant or baby IQ would appear to be, practically speaking, an impossible task. IQ tests reach their scores by requiring participants to show skill in math tests, memory tasks, vocabulary tests, and puzzles that quiz sensory perception. Considering babies are notoriously distractible and baby talk is a very limited form of communication, a standard modern test is essentially useless. That hasn’t stopped scientists attempting to design IQ tests for kids that will allow them to see into the future success of an infant’s mind. Perhaps the craziest thing about the weird world of infant IQ tests is just how close one scientist got to achieving a test for infants that could actually predict their future achievement.

In 1985 psychologist Dr. Joseph Fagan III appeared to find that infant intelligence was both knowable, measurable, and predictive of future intelligence. Up to this point, IQ tests for kids were for those who were five and older — the ones who could communicate well enough to offer answers to researchers. Psychologists such as David Wechsler used vocabulary testing, visual puzzles, math problems, and memory tests to provide an IQ score for elementary-age kids. In 1965, psychologist Nancy Bayley got closer, developing the Bayley Scales of Infant Development which was scored based on observation from test administrators. But the Bayley scales failed as an IQ test because the nonverbal motor behaviors observed in infants really have nothing to do with future cognitive abilities. A kid who grasps and manipulates objects early, for instance, does not necessarily turn into a smart adult.

Instead, Fagan found that a baby’s development of vision was a much better marker. In Fagan’s early research he discovered, through what he called novel paired-comparison tasks, that infants have the ability to recognize, retain and recall faces and visual information. The idea behind novel paired comparison is to present infants and babies with a series of image pairs, and then change one of the images in the pair. Researchers then measure how much time the baby spends looking at the new image compared to the image that they are familiar with. “Tests of visual novelty preference tell us that the infant has the ability to know the world,” Fagan wrote in a 1992 technical summary of his test. “If such processes of knowledge acquisition underlie performance on intelligence tests later in life, it is justifiable to assume that their exercise early in life represents intelligent activity on the part of the infant.”

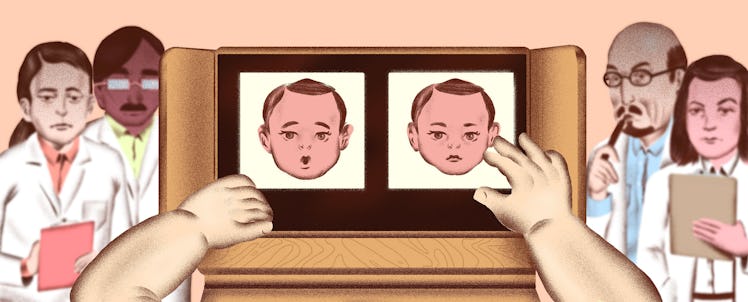

So Fagan got to testing infants. Parents held their babies in their lap while sitting in front of a small desktop stage into which a pair of images could be placed. The images used were pictures of men, women, and baby faces which infants are tuned to recognize. The babies were familiarized with image pairs before being exposed to a new pair featuring an image they had not seen before. Researchers, looking through a peephole, then measured how long the infant looks at the novel image. The infant went through four rounds of testing and is exposed to nearly 30 image pairs.

The Fagan test resulted in a “novelty score” comparing the amount of time an infant looks at the novel images to the time spent looking at the familiar images. More interest in novelty, he presumed, was associated with more intelligence and vice-versa.

Fagan’s claims that test results might predict future intelligence scores were met with skepticism. Fagan’s sample size was relatively small, there appeared to be an inconsistency between testing sites, and the predictability of the test couldn’t be known until far later, when the babies grew up. (Fagan himself conducted much of the follow-up on subjects, revisiting the babies when they were in high school to find that their scores on standard IQ tests correlated to their scores on the earlier infant intelligence test.)

But the biggest criticism came from the implications of the test. Many of Fagans contemporaries worried what labeling babies as intelligent or not intelligent could possibly mean for a kids’ future.

In a 1992 article published in the Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology titled The Fagan Test of Infant Intelligence: A Critical Review, lead authors worried the Fagan test might be used to recognize high-IQ babies for enrichment, which would “skim the cream and leave the rest behind.”

Fagan himself saw a greater social good, that it could be useful to recognize these children, particularly if they were from disadvantaged backgrounds. “’Why not test infants and find out which of them could take more in terms of stimulation?” Fagan told the New York Times in 1986. “It’s not going to hurt anybody, that’s for sure.”

Fast-forward a decade and the ironic prescience of this line starts to become apparent. Companies and authors skipped straight from the measurement of a baby’s IQ to ways for parents to increase said IQ. In 1996, the Baby Einstein videos came out, promising to boost a baby’s intelligence and give them a head start. Books like Raise a Smarter Child by Kindergarten and How to Multiply Your Baby’s Intelligence, followed suit, as did baby sign language, and baby music classes. All of these were marketed as boosting baby brain development.

In 2004, the toy company Fisher-Price more squarely aimed at the baby IQ test, commissioning one themselves from British psychologist Dr. Dorothy Einon. The test was essentially a 10-question quiz that asked parents to identify behaviors in their baby, like what they do in response to dropping a teddy bear or how many blocks they could stack. In an article in The Telegraph about the Fisher-Price test psychologists cast deep doubts, suggesting the quiz was unscientific and could unduly cause parents to stress out.

This point speaks most directly to the harm that these tests can do to parents. To give parents a pseudo-scientific measurement of their child’s IQ has little upside and a big gaping anxiety-inducing downside that calls parents to action — any action — that can help get their low IQ infant a boost, their medium-IQ baby a leg-up, or to help their supposedly high-IQ child to meet their potential.

“I’ve heard of elite preschools that use IQ type tests on babies during admissions,” says Dr. Celeste Kidd of UC Berkeley’s Kidd Lab. “When I hear about these places I never take the school seriously,” she says, because defining “intelligence” is an incredibly slippery task. “We don’t know enough about what intelligence is to be very worried about it. And that’s a good thing,” she says.

Despite the pile-on for the idea of boosting baby IQ, Fagan’s test — the original one in his studies — remained out of the public eye. Part of this was that he seems to have taken the criticism to heart. Fagan ultimately developed a computer program that could help researchers implement his test. The last edition of the manual was published in 2004 and Fagan had moved away from using the test to predict intelligence and instead insisted that it only be used as a diagnostic tool to recognize early signs of mental retardation.

“Recent advances in the study of higher cognitive functioning in the infant, via the observation of preferences for novelty, have led to the development of a valid test of early intelligence,” Fagan writes in the 2004 manual for his test. “It should be kept in mind that the Fagan test has been developed for the early detection of later mental retardation and should not be used for routine screening with normal populations.”

Kidd notes that diagnosing issues is a much more reasonable objective than predicting intelligence. That’s largely due to the fact that there is far too much that plays into our concept of intelligence — cultural cues, environmental issues, and even social factors could affect intelligence, not just genes.

Instead of looking for predictors of future intelligence through IQ tests for kids, Kidd suggests that parents instead focus on their child as an individual, with individual talents and challenges. While it’s important to keep an eye out for red flags that might indicate developmental issues, it’s better to judge your child against their own developmental path.

At the end of the day, intelligence and quality of life are very different things. IQ tests for kids could possibly measure intelligence, but more likely it measures a child’s cultural aptitude. Sure a baby that can recognize a novel face may be able to put a puzzle together faster at a 5-year-old, but that does little good if the child’s home is a miserable place to live filled with stressed-out parents.

More than intelligence, love, and trust are what seems to lead to the best outcomes for kids. Being stressed out about their intelligence, however, does not. “We have a lot of evidence that parental anxiety has known negative consequences on a child’s development and well being and ability to interact with the parents,” Kidd says. “Any product that could increase parental anxiety could have an unintended negative consequence of the welfare of a kid.” Which, no matter how intelligent your kid is, just doesn’t seem very smart.

This article was originally published on