What Makes Men Successful? Resiliency In Both Failure And Success

Money is good. Sex is good. Power is good. But nothing lasts without resilience.

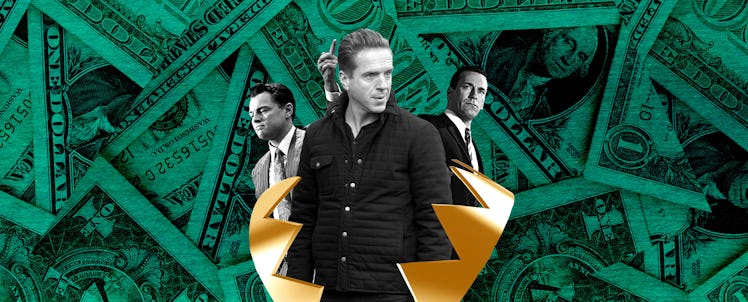

Thanks to the charismatic sociopathy of the fictionalized Jordan Belfort in the Wolf of Wall Street and his ward Bobby Axelrod on Billions, the high-performing asshole became the most popular figure in pop culture while also becoming, courtesy of disgusting performances by Matt Lauer, Harvey Weinstein, and Eric Greitens, the most reviled figure in public life. Celebrated on film and castigated on Twitter, immoral climbers inspire hero worship and hatred, while sharing a unique appeal. They put achievement first — above health, happiness, and social connection — and, in so doing, they exhibit a sort of unsustainable masculinity many men aspire to despite its extraordinary costs.

“Men are socialized to be achievement-oriented, and it’s well documented that rigidly internalizing that socialization can lead to men who have some pretty serious struggles with work and family balance,” explains psychologist Ryon McDermott who co-authored the recently published APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice for Boys and Men. McDermott notes that characters like Don Draper, Belfort, and President Trump, who has actively rewritten his own story, have more in common than their ruthless pursuit of achievement. “They are able to get money and success, but engage in some very risky behaviors and ultimately experience psychological distress and social isolation.”

And, yes, art imitates life. McDermott’s research has led him to believe that achievement-orientation can sometimes put men at extraordinary psychological risk. Chasing achievement, he says, is similar to being aggressive for some men: It is a traditionally masculine behavior that isolates and antagonizes when taken to an extreme.

This is particularly difficult to accept because achievement is not a bad thing. Specifically, it’s great for kids. Children who perform better in school, sports, and other extracurriculars are generally set up for healthy physical, psychological, and social development. The problem occurs when kids begin to equate achievement and self-worth — something particularly common in boys. At that point, both achievement and lack of achievement become destabilizing because success is implicitly understood to not be sustainable and failure is absolute. There is a reason that words like loser, deadbeat, and burnout are, gendered. In America, men have both more opportunities to succeed and the opportunity to fail in a way that permanently defines them.

“My hunch is that nine out of ten times when those terms are used it is aimed at men,” says Matt Englar-Carlson, co-director of the Center for Boys and Men at California State University and co-author of the APA guidelines.

Although masculinity is often misunderstood to be a constellation of manly traits, psychologists believe it is actually a sort of status that can be constantly earned, challenged, policed, and taken away. Because of this, masculinity is inherently precarious in a way femininity, which is more biologically and physically defined, is not. And achievement is one way boys internalize this early in their development. This can look a lot like male privilege. Parents are two and a half times more likely to ask Google if their son is gifted than if their daughter is and tend to invest more money in boys’ college educations as well. This teaches sons to value themselves — maybe a little too much — but it also drives home the idea that worth is tied up in accomplishment, which leads to disaster when accomplishments become scarce. Think of the high school quarterback and homecoming king who refuses to move on. More than one stereotype has emerged from truth.

“For some men — especially those who rigidly focus on achievement as their indicator of worth- what was once something positive in childhood can become a straightjacket as an adult,” Matt Englar-Carlson says.

It’s not just that achievement gives boys a place to fall from, but that other aspects of masculinity rob them of tools to get back up. Of course women fail and of course they are judged for it, and of course they tie achievement to self-esteem. The difference is girls learn from an early age how to express themselves and seek support. And their need for support — a universal human need — is not treated as a failure unto itself. Boys are taught that they’re even more inadequate after failing if they express shame or regret — unless it’s in the form of anger or aggression. Men bottle it up and suffer psychologically, which reinforces a negative feedback loop.

Psychologists at the APA are not the only ones who are concerned about men’s inability to fail gracefully. Psychotherapist Richard Loebl, who was not involved in the recent guidelines, sees this play out in his clinical practice regularly.

“Women know how to express their feelings and they feel revived by the nurturing they receive. When adult men are nurtured they often feel ashamed,” Loebl says.

Men are far more likely to internalize than process the emotions that follow failure, and the physical and mental health consequences of this are well-documented. Unemployment increases men’s risk for substance abuse, divorce, aggression, depression, and suicide. For some men, the loss of a job takes a bigger toll on mental and physical health than the death of a spouse. And the more men believe in traditional masculinity norms, the more likely to respond to romantic rejection with anger, aggression, and violence. Violence in societies with high unemployment is often horrific.

“Failure is about shame. We didn’t just get a B or C on the test. It’s much worse than an account that didn’t pan out. And rejection by a woman is nearly fatal to a man’s ego, which is all too fragile due to relentless and unreasonable performance demands,” Loebl adds. “Messages from our fathers and from society in general tell us that we must score points, make a lot of money, get the right girl, and win against the other guy.”

The most telling example might be this: Data shows that men who fail to get their partners pregnant are more prone to committing acts of domestic violence.

There have been some shifts in recent decades to how achievement is gendered, most have short-changed boys. Since the 1950’s, boys have been falling behind in school compared to girls. They currently account for a majority of D’s and F’s in most schools as well as the majority of disciplinary cases. They are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and other learning disabilities, more likely to be medicated, and represent 80 percent of high school dropouts. Many studies suggest that the reason boys are falling behind is not because boys are less intelligent or capable, but because the education system plays more to girls’ strengths biologically — namely their ability to sit still and concentrate — while providing antsy young men with too many opportunities to define themselves through failure. This has already begun to gender academic success, which no longer seems to constitute a masculine achievement. Perverse incentives proliferate.

“The social costs associated with engaging in academics, which has become coded as feminine, coupled with men’s socialization to not appear feminine is greater than the perceived short-term social benefits,” explains psychologist Christopher Liang, who also co-author the APA guidelines.

In other words, men’s willingness to be defined by achievement can turn genuine achievement into an identity crisis at speed.

It’s important to note that this does not mean parents should discourage boys from trying. Additional research from the APA identifies 11 potential domains of positive masculinity, including male self-reliance, the worker-provider tradition, and service. These are not just semantically different; they are substantively different than achievement orientation because they do not assume that one is playing a zero-sum game. Achievement is still possible within these parameters, but so is failure.

“It’s not a matter of whether achievement is good or bad for men, it’s more of a question of how men conform to norms of achievement,” McDermott says. “It’s great to be focused on achieving things in life, but if you do that to the exclusion of everything else that makes you happy, you might start to suffer psychological consequences.”

Many attentive parents have begun preparing girls for how they will be judged based on their appearance. Similarly, parents may need to have conversations with their sons about accepting failure, understanding that the messages sent by broader culture may be damaging. The question then becomes how to help boys develop their self-worth. That’s harder and more personal. That’s where the rubber hits the road. ,

But just because finding alternative ways for boys and men see themselves is hard, does not mean it’s not possible or not important. It’s critical for the wellbeing of everyone. Men who don’t know how to fail are dangerous not only to themselves but to others. The problem with Bobby Axelrod and Don Draper isn’t just that they are bad men; it’s that they are bad men working within a system the reinforces their badness.

“We can better prepare boys for failure by letting them know they have intrinsic value. They are good enough because of who they are,” Loebl says. “When we teach boys that their emotions — their feelings of anger, sadness, shame, and fear — are normal, valid, and worthy of love and support, it actually encourages them to keep trying.”

This article was originally published on