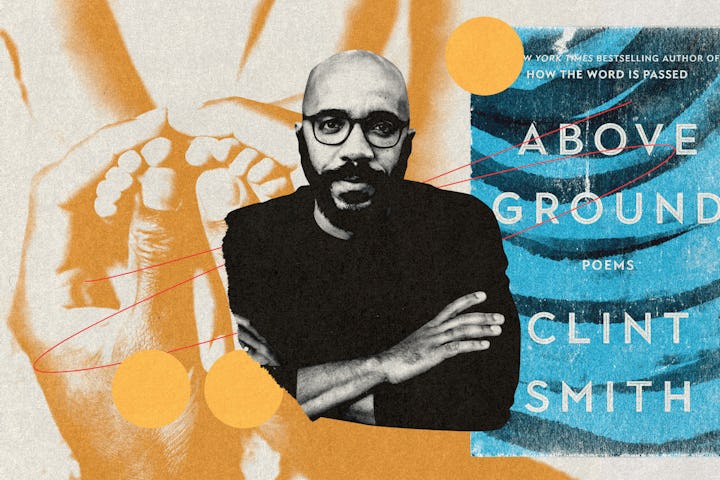

Clint Smith On Fatherhood, Fate, And The Fine Art Of Silliness

The acclaimed writer discusses his new poetry collection, the joys and challenges of parenting, and jotting down ideas during episodes of Peppa Pig.

For years, doctors told author and poet Clint Smith and his wife, Ariel, that their chances of getting pregnant were miniscule. So when, about seven years ago, they found out that Ariel was in fact pregnant, Smith began to process the experience in the medium he felt most comfortable with — poetry.

The medical condition that made it difficult for Smith and his wife to conceive also made her pregnancy tenuous. “When we did conceive, it felt like this sort of miracle had happened. But miscarriages happen to people all the time,” recalls Smith. “I think the sense of fragility and uncertainty stemming from a fear of not being able to conceive was then sort of just transmitted into the fear of being able to carry to term.”

Poetry continued to ground Smith through that first pregnancy, as he entered fatherhood, and even as a dad to two children who are now 4 and 6. While not his first dialect, poetry is an expression that Smith is undoubtedly fluent in. His collection Counting Descent won the 2017 Literary Award for Best Poetry Book from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association and was named a finalist for an NAACP Image Award.

In 2017, most of Smith’s public facing work shifted to a more narrative and journalistic style when he started writing for The Atlantic and working on his critically acclaimed book How The World Is Passed. But at his core he was still a poet, and it was through poetry that he would continue to explore fatherhood and the world in which he was raising his children.

A selection of those poems Clint wrote over the past six years have been assembled in his new book, Above Ground. It's a collection that is as sprawling and diverse in subject matter as life itself. The book contains an ode to the electric baby swing, another to baby hiccups and yet even another to baby smiles. It also examines the horrors of drone strikes and Willie Francis, the first known person to survive an execution by electric chair.

“Broadly speaking, this collection is trying to explore the simultaneity of the human experience,” says Smith. “How do we hold joy and wonder alongside fear and despair and shame? And what is it like to sit — to put those two things alongside one another because they exist alongside one another in our real lives?”

The end result is a poetry collection that runs the gamut of emotions, sometimes with no buffer between conflicting feelings. Fatherly spoke to Smith about the power of poetry, the joys and challenges of parenting, and how he manages to create while remaining an emotionally present parent.

In a couple of your poems you mention the precarious nature of your wife's pregnancies. Did doubt and fear persist throughout both of them?

Yeah. Part of the fear was animated by the fact that becoming pregnant felt so uncertain in the first place. We were told that we had less than a one-percent chance of getting pregnant. So even the possibility of having children when we began to consider it seriously was so fragile, so precarious, and so unlikely in many ways.

I don't know that there was a moment where we felt out of the woods until each of the kids were born. She was in so much discomfort and so much pain and because you never knew when things were gonna happen. The entire process was shaped by fate, by a sort of ongoing sense of peril.

It was all made more difficult by the fact that at the beginning, the doctors didn't believe what she was saying about the symptoms. They thought it was psychosomatic and obviously that's representative of something much larger for Black women across this country. They experience it all the time, which has been documented in studies that have come out recently.

How do we hold joy and wonder alongside fear and despair and shame?

When you started writing the poems that now make up Above Ground, did you intend to collect and publish them at some point?

No. I didn't begin thinking about this as a book. I think I began writing these poems when my wife got pregnant as a means of examining and reflecting on the experience. Each poem kind of serves as a time capsule of where I was at different points in time and where my children are at any given point in time.

In the same way we might with a photograph or with a video on your phone, it's a way for me to hold on to a moment that might otherwise be fleeting. And to also excavate that moment and explore it with a certain level of intentionality and specificity.

What effect did writing these poems have on you?

It ultimately makes me more present. It makes me more fully appreciate these moments. Time can go by so quickly. I can't even believe my oldest is almost 6 you know? Whenever I watch him sort of tumble into kindergarten with his oversized backpack — seeing all these fifth graders running around this little kid — I realize he was just a baby and now he's in kindergarten and then he’ll be one of those fifth-graders in no time.

You know that cliché that the days are long, but the years are fast? Some things are cliché for a reason, just because they're true. And I absolutely feel that with my kids.

Has your creative process evolved since you became a dad?

I was disabused of the idea very quickly that I would have these sort of long luxurious times to write where I could sit with my herbal tea next to the window and let the sun hit me while I have some smooth jazz playing in the background. I recognize that my creative process has to be a proactive practice. And so I write wherever I can, whenever I can.

I write in the DMV when I'm waiting for a new license. I write in the pickup line waiting to pick my kid up from aftercare. I’ll write during episodes of Peppa Pig or when I'm waiting at the barber shop.

You know that cliché that the days are long, but the years are fast? Some things are cliché for a reason, just because they're true. And I absolutely feel that with my kids.

How long did it take you to come to terms with the necessary reality for a new creative process?

I had a conversation with a mentor years ago. She has two kids and she told me to let go of this idea that I’d have these long periods of time to write. If you got 10 minutes, 15 minutes, if you can only write a paragraph or you can only write a few lines, take advantage of that time. And let go of the idea that writing has to sort of strike you. No, you have to strike the writing.

So it didn’t take long. It felt intuitive for me because I was an athlete and a soccer player growing up and so I was used to the idea that you show up and practice even on the days you don't want to. Then on game day, that is the manifestation of the work that you've been putting in during practice.

Writing is the same way. I've written quadruple the number of poems that are in the book, but I had to write those poems to get to the poems that I felt good about publishing. That doesn't mean they were a waste of time. It just means it was part of the process of getting to what I wanted to put out in the world.

How do you envision sharing the published poems with your kids?

I read many of the poems to my kids and they're interested in them to varying degrees. It depends on what's happening or if there's an episode of Peppa Pig on that they want to watch or a soccer game they want to play. But I'll be interested in the ways that these poems exist for them in the future — what it's like for them to have this sort of poetic archive of this time in their life, through my eyes, and what it will mean for them to see themselves in the way that I saw them. I hope it's special. I hope it's meaningful.

What about the more intense poems? Because they do span a wide range of content and emotions and some might be too heavy for kids to understand.

We try to have conversations with our kids about the realities of the world. The realities of our history. The realities of the history of their own lineage as Black children. So we talk about inequality. We talk about racism, we talk about sexism, we talk about all of these different topics, but obviously we do it in a way that's developmentally appropriate.

We do it in a way that's not going to traumatize them, that's not going to leave them scarred, but we do try to open up the space for them to understand and examine the parts of the world that are worth celebrating and the parts of the world that are in need of work, and to make clear to them that both of those realities are part of our part of our world that we should understand alongside one another.

I write in the DMV when I'm waiting for a new license. I write in the pickup line waiting to pick my kid up from aftercare. I’ll write during episodes of Peppa Pig.

One of the sweetest images in Above Ground is of you reading Dr. Seuss to your kids while they're in the womb. And that might come as a surprise for people who might expect that an accomplished poet is going to read Shakespeare sonnets to his kids. What is it about Dr. Seuss that brings joy and still stands up over time?

I mean, it's just silly. And it leans into the silly. I want my kids' lives to be animated by silliness and fun and levity. I want them to be kids and to make up words, to laugh when they hear “Yertle the Turtle” or “Circus McGurkus.”

I think the silliness of Dr. Seuss is reflective. It allows you to be reminded that this hard and exhausting, life should also be fun sometimes. It shows you the parts of yourself that you are proud of and parts of you that you're not so proud of.

But also, having little kids is just fun. They’re funny little humans who think that the world is a fun and silly place. When you read books by Dr. Seuss, oftentimes, it gives you the chance to revel in that alongside them.

This article was originally published on