How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Our Messy Household

For a long time, my wife and I worked tirelessly to keep our house spotless. Then, we calmed down and realized the mess of a home is merely proof of life.

A few weeks after our first child was born, a nurse came over to the house. Newly terrified about our parental responsibility, my wife and I had finally decided to buy life insurance. The nurse was there to draw blood and make sure we didn’t have malaria or high cholesterol.

As she prepared her equipment, the nurse sneezed a few times and said, “I’m really allergic to dust.”

I looked into the face of the mother of my child and saw it cloud into the color of an approaching typhoon. She was sleep-deprived and recovering from a C-section, nursing a baby at all hours of the day and night. And now a stranger was insulting her housekeeping. I braced for the onslaught.

Then the nurse realized her mistake, apologized, and we all laughed it off.

Nah, I’m joking. They never found that bitch’s body.

In the years before children, my wife and I cleaned with enthusiasm. We Swiffered and vacuumed, we scrubbed and polished, we swept and mopped. The couch pillows were plumped, the bed was made and the clutter was boxed and labeled. We’d spend weekend hours moving through the house systematically, blasting tunes, putting things in order. We’d invite people over for dinner, and I’d pick crumbs up off the shining floor and load the dishwasher while our guests chatted uneasily, noticing the way their existence in my home made the place unclean.

In those early years, we weren’t keeping the house tidy so much as proving a point: We. Were. Not. Our. Parents.

Her mother and my father subscribe to a similar housekeeping philosophy. If one were to stitch their maxim onto a decorative needlepoint, it might say, “Retain your possessions forever and display them exorbitantly, no matter their trifling value.”

In those early years, we weren’t keeping the house tidy so much as proving a point: We. Were. Not. Our. Parents

When I was a teenager, I felt deep shame about my dad’s messy house. It wasn’t full of rotting trash — it was full of stuff. Car parts and broken furniture and old records and paperwork he’d brought from the office. Dirty dishes sat in the sink, “soaking” for weeks. I worked hard to keep my friends away, worried that I’d be judged a crazy person for living like that. I kept my room clean, and he’d talk about wanting to get things organized and squared away, about wanting to spruce the place up a bit, but it never happened. He hasn’t changed.

The last time we were at his house was more than two years ago. This is what I saw in his office: a metal shelf stuffed full of boxes and a red bucket, which contained a wooden ruler, a bottle of hand sanitizer, and a washed out, empty peanut butter jar. On top of everything, a folded up Virginia Tech blanket was stuffed into a transparent plastic bag. No one in my family has attended that university.

There was a bookcase containing titles like Sidetracked by Henning Mankel, The Complete Walker by Colin Fletcher, and Radical Integrity by Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Intermixed with the books were about two dozen AAA road maps and VHS copies of The Victor Borge Collection and Legends of American Comedy, highlighting the careers of Lucille Ball, George Burns, and Gracie Allen. There was an empty picture frame, several photo albums, and a fly swatter. In the closet, I found the dual cassette/CD player/turntable stereo I owned in high school. The speakers were missing.

As I stood in that room looking around, I didn’t feel shame. I felt dread. I’m going to be clearing all of this crap out of here someday, I thought to myself. When we returned home, I cleaned our house with ferocity and vengeance.

A few months ago, I walked down the street looking for my daughter. She’d been playing with some neighborhood kids and had disappeared into one of their houses. I walked up the front steps and through the open door, pissed off. I was ready to read her the riot act for wandering away without telling me where she was going. Then I took in my surroundings. The mess in this house was astounding. Shoes and toys and electronic devices and clothing and backpacks and kitchen utensils and all sorts of other random crap were strewn across the entire square footage of the first floor. I spent several moments staring at the scene. When I could speak, I called out for my daughter and we walked home. I didn’t read her the riot act. I was too shell-shocked.

For weeks afterward, I thought about that messy house, and what it meant to me, trying to figure out what it meant about the people who live in it. I wasn’t repulsed. I was fascinated. That family was living a freedom I’d been too timid to experience.

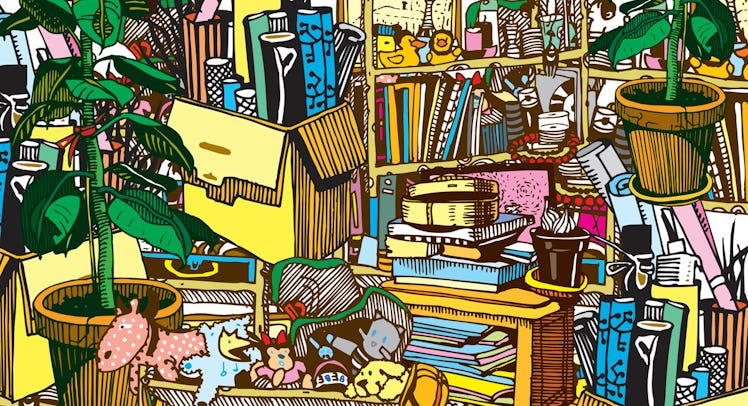

They didn’t see clutter and disorder and chaos, all begging to be straightened up and squared away. They saw proof of life. They were displaying evidence of imagination and play and nourishment. They weren’t living for their dinner guests, displaying a spotless showroom. They were living for themselves, for each other. The house wasn’t clean. But it was comfortable.

I thought about that messy house, trying to figure out what it meant about the people who live in it. I wasn’t repulsed. I was fascinated. That family was living a freedom I’d been too timid to experience.

All at once I remembered a friend of mine in college. He was an artist. His dorm room was always stuffed full of huge sheets of paper, bits of fabric, twists of metal, odd lengths of wood, charcoal pencils, and oil paints. You’d sit there, looking at the jumble of creation, and feel like you were sitting in a gallery, viewing the whole tableau and waiting for specific items to pop into your consciousness. His room was his mind, on display outside his skull. You could relax there, settle in, feel the weight of years of work nestle around you like a blanket. The bric-a-brac was alive somehow, holding history, animated by devotion.

That’s how I felt standing in my neighbor’s house.

All those years my wife and I were busy proving to ourselves that we weren’t as messy as our parents, we were not yet parents ourselves. All at once, I saw the mistake in our equation.

Now that I’m 10 years into parenthood, you’ll find a shelf in my basement that holds giant blue IKEA bags, indoor soccer shoes, two kites, and a bubble maker. In my office closet under the stairs, there are half a dozen external hard drives, a team of wobbly GI Joes and a file box of my dead mother’s medical records. Chess pieces mingle with matchbox cars and Legos in the playroom. Unused car seats are stacked in the corner of that room, next to a shabby armchair and the drying rack covered with last week’s laundry. It’s no better upstairs. Broken seashells adorn the mantle, the dining table centerpiece is a stack of our son’s paper-and-tape artwork, and the shelf by the door holds unopened bills, a single mitten, and the unused knitting supplies. All these objects have a right place, but they meander from their pens, out into the open, over and over again, until we relent and let them live where they lay. The clutter has nestled around us.

All those years my wife and I were busy proving to ourselves that we weren’t as messy as our parents, we were not yet parents ourselves. All at once, I saw the mistake in our equation.

I see that now, and I accept it. The trick is to find the balance between “carefree artist” (my college friend) and “Unabomber” (my dad), like a crusty plate balancing on the edge of a stack of Sunday newspapers.

My wife has come a long way since she murdered that nurse. We’ve got family coming to visit, and I’ve been stressing out about finding the time to clean the house. I also have to find time to drive the kids to practices and rehearsals, time to take the cat to the vet again, time to work. Even a few years ago, my wife would have gone all Tasmanian Devil with me, chucking the paper-and-tape artwork into the trash, boxing up half the toys, scrubbing the grout with a toothbrush, vacuuming the cats. Not anymore. “Who cares if the house is dirty?” she said to me last night. “It’s just my sister.”

The kids beat us. We lost. Turns out we are just like our parents. Hope you don’t mind the mess.