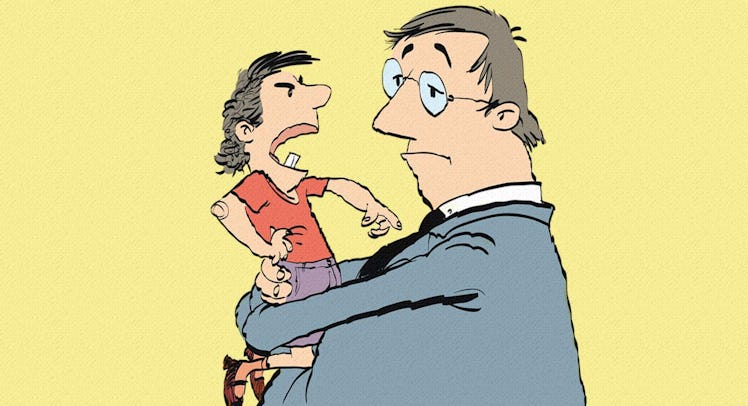

Zen and the Art of Not Reacting to Children’s Bad Behavior

Why keeping calm and not reacting may be the perfect antidote to bad toddler behavior.

My two-and-a-half-year-old has a new favorite pastime: He runs up to one of our many cats, frightens them with a blood-curdling shriek, and giggles when they run off.

“I scared the kitty,” he laughs.

“Be nice to the kitty,” I warn.

For the most part, this pastime is harmless. He doesn’t pull their tails or yank on their fur. Our cats are able to escape of their own accord. They only endure vexation.

Still, since this behavior started, I’ve noticed myself developing an equally worrisome habit: chastising my son before he does anything to the cats. A cat enters the room, my son’s gaze immediately turns toward his feline victim, a small smirk emerges, and, before he can spring; I bark.

“I know what you are thinking. Don’t do it.”

My wife has noticed this too. “You need to let him make the wrong choice sometimes,” she says. I know she’s right. Preemption isn’t really a good parenting technique. Children must learn that all of their actions carry certain consequences. Often times, the best response to my son’s objectionable behavior is no response. As a relatively new parent, I both know this to be true and struggle to apply that knowledge. I am learning the art of sitting on my hands.

Read more of Fatherly’s stories on discipline, behavior, and parenting.

Of course, there are situations that warrant a swift and immediate reaction. If my son is on the verge of causing significant harm to himself (“Sorry, bud — you don’t get to drink that entire bottle of mouthwash”) or others (“Please stop trying to shove your cousin into the fireplace”), intervention is justified. But these occasions are rare. Also, we don’t have a fireplace.

My son’s bad behavior is typically a cry for attention. For example, my son has another frustrating habit that involves a small plastic table set. This table set (complete with four chairs) serves multiple purposes: a table to snack off of, a desk to color on, a race track for his cars, etc. He views it as a tool for expressing his rage. When he feels like his planned itinerary has been interrupted the table falls victim to my son’s outrage. A low-level response usually entails knocking one or two of the chairs down. A high-level response involves a WWE-style chair or a forearm swipe that shoves all of the table’s contents onto the floor.

I see it coming.

“Don’t do it,” I sternly caution, as my son begins his pre-tantrum ritual by running toward his table set. “That table didn’t do anything to you.”

That, of course, doesn’t stop him, and I am left cleaning up the plastic carnage.

“What good did that do?” my wife comments, as the toddler runs away into another, crying the whole way. “You’re just giving him the attention he wants.”

Sigh. Again, she’s right. My son understands the power of the tantrum as an effective means of marketing. There is no such thing as bad publicity, right?

Lately, my reaction to the table fiasco has relied upon the principles of Stoicism. The ancient school of philosophy emphasizes the value of logic, serenity in the face of adversity, and avoiding the trappings of emotionalism. When my son dismantles his table set, I must accept what is happening and avoid an overly emotional response. I’ve noticed that remaining calm is a successful tactic for disarming the tantrum. If I am to expect my son to be resilient when facing hardships, then my only choice is to set the example.

Just now, I hear my son crying in the other room. His moans increase in volume as he runs towards me and my wife.

“I… hurt.” His blubbering speech pattern is spliced with exaggerated sobs between words. “Kitty… scratch… me.”

My wife reaches down and hugs him. “There, there,” my wife says. “That’s what happens when you mess with kitty. You probably deserved it.”

My child will likely fall on his face — literally and figuratively speaking. The lesson that I am learning as a parent is that I can’t stop him from falling. In the early years, my role is to help him back up and provide insight into why he fell. But, as he grows, this is a lesson that he increasingly will need to learn on his own. And the best thing that I can do is stay close for those moments when he asks for help.

This article was originally published on