The One Thing All Angry Men Have In Common

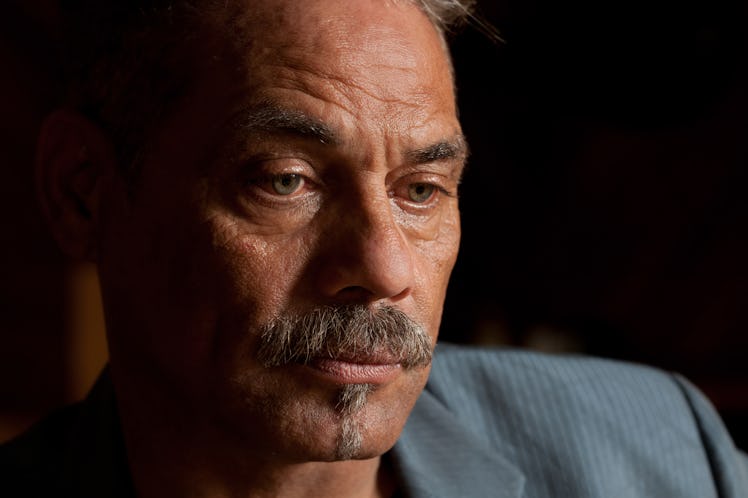

An anger management expert peels back the layers of anger in men to find a source — and a salve.

When Dr. Thomas J. Harbin published his seminal work Beyond Anger: A Guide for Men in 2000, it was a simpler time. Sort of. Anger, especially among men, was a widespread problem, but it was hardly so communicable as it is today. Now, anger travels like a virus, transmitted from the individual to the masses with the tap of a touchscreen. As he writes in the prologue to a new edition of Beyond Anger, the social media age has proven “perversely liberating” for angry men.

“They don’t have to deal with the consequences of angry diatribes and don’t have to fear retribution,” he writes. “They can say whatever they want to whoever they want and get away with it. They can rant and rave, call people names, make false statements about people, start or contribute to rumors, and sometimes ruin lives — and forget all about it when they walk away from the screen.” This behavior, he concludes, is nothing short of cowardly.

A clinical psychiatrist practicing in North Carolina, Dr. Harbin spent decades working with angry men and their families, teaching them to come to terms with and control their anger. In that time, he’s come to a robust, nuanced understanding of anger, where it comes from, how it works, and how people can deal with it. We spoke to Dr. Harbin about what he’s learned, why anger is so present today, and what men can do to manage theirs.

For readers who might be unfamiliar with your work, could you briefly outline a working definition of male anger and how you think about it?

I think that male anger is probably like everybody’s anger, only that men tend to express it differently than women. Men tend to be more physically aggressive than women, men tend to be more verbally aggressive than women. But I think in general, anger is anger.

And how did you come to specialize in anger?

The first aspect of it was trying to deal with my own anger as a young man. So I started putting some of my thoughts down on paper. I’m a clinical psychologist, so in dealing with some of my angry male patients, I wanted to have something that they could read. There weren’t any books out there at the time that I really thought fit the bill, so I started writing a few chapters here and there and then decided to expand it to a book.

How have cultural understandings of or approaches to anger changed throughout history?

I think that public recognition of some of the behaviors that we used to accept is no longer there. While we are a long way from dealing with a lot of the anger-related problems in men, there’s at least, now, a recognition that physical aggression is usually not acceptable, that yelling and screaming at family or co-workers or other people is not acceptable. So I think the acceptability of a lot of traditional angry male behavior is starting to erode.

A lot of angry men have a core sense of inferiority. They feel like they don’t measure up.

Other than your own work on the matter, do you have any sense of what the drivers are of those norms changing?

The last couple of generations of men — well, the two generations after the World War II generation, so baby boomers and then the generation after that, have really been caught. In former times, the definition of a man was you went to work every day, you worked with your muscles, you brought home a paycheck, and that was about it. And now women can do most of the work that men can do. The definition of what it is to be a man now is in flux, and I think that’s unsettling to a lot of men now. We don’t really have a hard and fast rules for what it means to be a man and a successful man. I think that causes a lot of dissatisfaction that gets expressed as anger.

A lot of angry men have what I call a core sense of inferiority. They feel like they don’t measure up. And then there is an idea that a Dr. [Michael] Kimmel has put out there in some of his book which he calls “aggrieved entitlement.” And that is a lot of men, especially white men, feel like other people are getting stuff that I’m entitled to and I’m not getting it. So I think it’s a complex that has changed over the last 20 or 30 years.

Can you talk about that core sense of inferiority and what its root are?

Well, physical abuse. That teaches a boy that he is not a person, that he is an object, that whoever is abusing him can do whatever he wants with him — especially hitting on the head, that’s a humiliating thing that leads to feelings of inferiority. I think, again, the confusion as to what it means to be a man these days contributes to that. We’ve had some significant financial down turns in the last 20 years — the dot com bubble in 2001, the big recession in 2008. I think all of those challenged a lot of men’s self-confidence and caused them, a lot of times, to have to reexamine their identities as men.

A lot of people value belligerence in and of its own self. Belligerence is now a virtue.

How have your own views about anger and attitudes toward treating and addressing anger changed over the years, as you’ve practiced?

I am concerned. I think over the last 10 or 15 years or so a lot of aspects of our culture have gotten increasingly aggressive. There is an acceptance of humiliating trash talk in sport, many of our political bodies sit and scream at each other instead of getting anything positive accomplished, I think a lot of people value belligerence in and of its own self, so that belligerence is now a virtue. I think there’s a lot of disturbing trends in our culture in the last 20 years.

Angry young men are in the news a lot these days, between men’s rights activists, the Proud Boys, so much of the alt right. And that seems to intersect so much with social media and the ways we live online. I’m curious what you make of that, or what you’ve learned about that in dealing with your patients?

I think the echo chamber has done a lot to exacerbate and perpetuate male anger. Guys can go online and find thousands of other guys that are just as angry as they are and they bounce it back and forth, getting angrier. I think that there has been a great reduction in civility and reasonableness over the last couple of generations, and I think that you’d be wrong to blame social media for that entirely but I certainly think that social media contributes to it. It used to be that if you wanted to get a bunch of people together to complain about something, you had to make some sort of telephone or mail contact, you had to arrange a place to be. And now people can just go ahead with a few clicks and they’re connected to thousands of people that are just as angry as they are.

I’m fascinated by these connections between anger on a small scale and on a macro scale. Are there any commonalities, do you think, between how a society can remedy anger and how individuals deal with it in their own lives and families and relationships?

I think that society sets the parameters. So parents, teachers, coaches, other authorities set the bar for what is acceptable and what isn’t. So that’s sort of society’s contribution. And then the individual has to find ways to live within those rules or suffer the consequences. And I think a lot of the social parameters are in flux right now. I just think back to when I played high school sports — if I had done some of the things that are accepted now, I would have been sitting on the bench. Coaches would not put up with it.

Anger is not bad, anger is not good, it just is.

What tips or recommendations would you give to a parent worried that their child might have anger issues?

I think that there needs to be consistent discipline. By that I don’t mean punishment, I mean that there — I think of my brother as being almost the perfect father, in terms of training his kids. He would say this is what I expect out of you, this is what will happen if you do what I expect, this is what will happen if you don’t do what I expect and then follow through with it. And he rarely had to raise his voice, because his daughters knew that if they did X or Y, then it would happen.

So I think consistent discipline is a good way to raise kids that are not angry. I think that by and large when parents hit their kids, they’re teaching them that that’s the way to solve problems. So I think a de-emphasis on physical punishment, and I think kids just need to know what the rules are and what will happen if they don’t follow the rules.

And suppose you’re talking to a father whose is worried that they themselves might get angry with their kids, who feel the anger bubbling. What do you say them to deal with that?

The first thing I would say is that anger is not bad. Anger is not bad, anger is not good, it just is. And it is for its own reasons. What we worry about, or at least what I worry about with my patients is: What does it take to get you angry, how angry do you get when you get angry, what do you do when you get angry? Those are the things that I like to focus on. But if a parent — let’s say a father — feels as if he is going to get out of control with his kids, the first thing he’s got to do is walk away until he cools off. Later on, maybe he can learn more sophisticated ways of dealing with his anger, but the first step is to get out of that situation so you don’t do anything that you’ll regret later on.

This article was originally published on