What Baby Boomers’ Parents Did Wrong

One did not ask a widget whether it approved of the means of its production. Why would children have been different?

The following is an excerpted taken from A GENERATION OF SOCIOPATHS: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America by Bruce Gibney, published March 7, 2017, by Hachette Book Group.

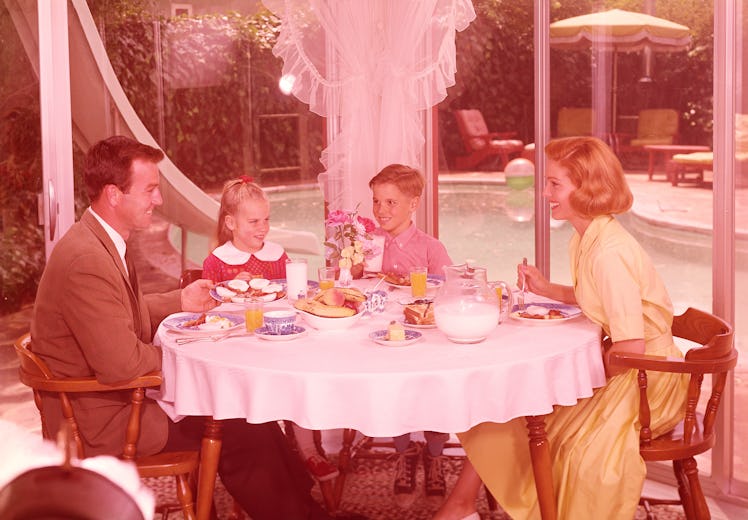

The popular television show Leave It To Beaver, which debuted in 1957, provides a fair portrait of Boomer childhood. The show’s utter lack of imagination was both its artistic vice and sociological virtue. Compared to today’s operatic contrivances and reality television, Beaver was pure anthropological rigor. The subjects of study, the Cleaver family, were studiously unremarkable: two parents (Ward and June), two kids (the Beav and Wally; presumably the statistically required fractional additional child would have been unsettling to display), plunked down in a suburban house enclosed, inevitably, by a white picket fence.

Ward was a World War II veteran who had attended a state college, presumably on the GI Bill, and worked at a trust company; June ran the house. The Cleaver children were both Boomers, notionally born in 1944 and 1950, and raised in ways that would have been instantly familiar to their peers on the other side of the set — and alien to their grandparents. For above all, Ward was a soft touch, a sharp contrast to his own father, an ancien régime monster of discipline and corporal punishment.

Childrearing: Dawn of Time–AD 1946

If the oldest Cleaver’s methods shock now, that was not the case for most of human history. Grandpa Cleaver’s methods were those by which children had long been raised. The old system was not without its grim logic. Because of high infant mortality – even in the 19th century, it was not uncommon for 20% of children to die before age 5 – parents saw no reason to invest substantial material or emotional resources until it was clear a child would live. Should a child survive, parents would set themselves not to the arrangement of playdates and other diversions, but to the production of a miniature grown-up, conformed to adult notions of virtue and industry, ready for near-immediate employment. Dialogue with children was unnecessary and motivation best supplied by the stick.

Even more enlightened approaches, which began appearing in the 17th century, were unforgiving. John Locke, famous now as the expositor of the social contract (something the Boomers would gleefully rip up), was more renowned in his time as a childcare expert. His Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), progressive though they were, inclined toward discipline (a word appearing an average of twice a page in my edition of Thoughts). Locke’s goal had been to produce “virtuous, useful, and able men” by the “easiest, shortest and likeliest means,” and that certainly did not entail pampering of the kind the Boomers received.iv

The behaviorists of late-19th century America, whose thinking dominated the rearing of the Greatest Generation, shared Locke’s goals. They had only to look at the country industrializing around them to know how Locke’s 17th-century process might be improved. Locke’s character-forming exercises, which depended on weird exercises involving leaky shoes and hard beds, were too haphazard for the modern world. Henceforth, good children would be manufactured by a rationalized process of positive and negative reinforcement, delivered immediately, and unburdened by Locke’s philosophical meanderings about human nature. In 1899, “less sentimentality and more spanking” was the order of the day, according to G. Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, psychologist, and childcare authority. If children didn’t like it, that was beside the point. One did not ask a widget whether it approved of the means of its production. Why should children be different?

Like Hall, Dr. Luther Emmett Holt of Columbia University favored the scientific rearing of children and his views enjoyed enormous influence. Holt’s The Care And Feeding of Children (1896) was a best-seller, eventually repackaged by the Government Printing Office and widely distributed as a sort of state-sanctioned guide for childcare. Like factory workers and farm animals, children were not to be indulged, they were to be managed. While the specifics of these behaviorist texts differed from prior practice, the central insights about child care remained the same until the 1940s: children were to be formed according to their parents’ wishes and society’s needs, with parenting a matter of coercing useful behaviors, instead of catering to childish whims. Given the bottomless thrift, industry, and manners of the Greatest Generation, perhaps these ideas weren’t meritless so much as victims of excessive zeal.

Dr. Spock and the Rise of Permissive Parenting

Rigor was therefore the dominant practice for American children until Benjamin Spock changed things in an instant. Spock was, like Locke, a trained physician, with a specialty in pediatrics. With the assistance of his wife, he produced The Commonsense Book of Baby and Child Care, first published in 1946, in time to guide Boomer upbringings. A best seller of tremendous proportions, it sold 500,000 copies in its first six months, and in the half century following its printing, was surpassed only by the Bible in sales (or so the story goes). A contemporary poll of American mothers showed that 64% had read Spock’s book and even those who didn’t own a copy couldn’t help but absorb its precepts; excerpts cropped up everywhere, with snippets even appearing on I Love Lucy and implicit in Beaver. The defining text of Boomer youth came from Dr. Spock, not Kerouac or Pirsig.

The Commonsense Book’s treated every imaginable topic, but its core injunctions were always the same: that parents rely on their own instincts and accommodate children’s needs wherever reasonable. In a radical departure, the Commonsense Book even strove to comprehend a child’s worldview from the perspective of the child himself, a task conservatives viewed with apprehension. In the preface, Spock stated that his “main purpose in writing [his] book was to help parents get along and understand what their children’s drives are.” Older traditions could not have cared less about “understanding” a child’s motivations.

Unlike his predecessors, Spock did have psychological training and he disdained the old fixation on discipline and distance, instead emphasizing loving care, physical affection, and a degree of deference to a child’s impulses. His attitude towards toilet training is instructive. Previously, experts advised a regimented approach, with children to be trained at three months (one wonders how) and evacuations taking place on a set schedule, Taylorism for tots. This, Spock believed, was an exercise both destined to fail and that risked the development of certain neurotic compunctions, like an anal-retentive personality overly fixated on tidiness and orderliness, though likely to be productive and deferential to authority (e.g., the Greatest Generation). Instead, Spock encouraged parents to let children set their own defecatory timetable, a system not without its own dangers. Freud had warned that indulgent toilet training could lead to an anal-expulsive personality, one that proceeded from literal to figurative incontinence, personalities of messiness, disorder, and rebelliousness (e.g., the Boomers).

Part of Spock’s relative leniency came from his radically optimistic views on human nature, his belief that children would grow up well so long as their parents provided a good example. Spock wrote that “discipline, good behavior and pleasant manner…You can’t drill these into a child from the outside in a hundred years. The desire to get along with other people happily and considerately develops within [the child] as part of the unfolding of his nature, provided he grows up with loving, self-respecting parents.” Two thousand years of parenting experts would have disagreed; parents most definitely could drill habits into a child, with the notion of relying on a child’s good nature to achieve the desired results being the very definition of insanity.

Cultural conservatives predicted that America would collapse in lockstep with discipline’s decline, and they were not entirely wrong. Norman Vincent Peale, a preacher famous for writing The Power of Positive Thinking, characterized Spock’s method of childrearing as “feed ‘em whatever they want, don’t let them cry, instant gratification of needs.” Peale blamed Spock for helping create the culture of permissiveness in the Sixties and he was not alone, though Peale and other critics failed to consider Spock’s text as a whole. The Commonsense Book did allow for spanking as a last resort – it just preferred to deploy gentler options first. Still, in missing these nuances, the conservatives might have proved their point. Spock’s book was not supposed to be read front-to-back like a novel, but topically, like a guidebook, consulted to resolve a particular problem on a particular day. To the extent this structure made it possible for parents to overlook a few admonitions about laxness, Peale was inadvertently correct.

Excerpted from the book A GENERATION OF SOCIOPATHS: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America by Bruce Gibney, published March 6, 2018 by Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2017 Bruce Gibney.