David Giffels Built Coffins With His Father. Then His Father Died.

"The last gift that my dad gave me was to show how important it is not to waste time, and to use your time for the things that you're aware that you should be doing, but sometimes don't."

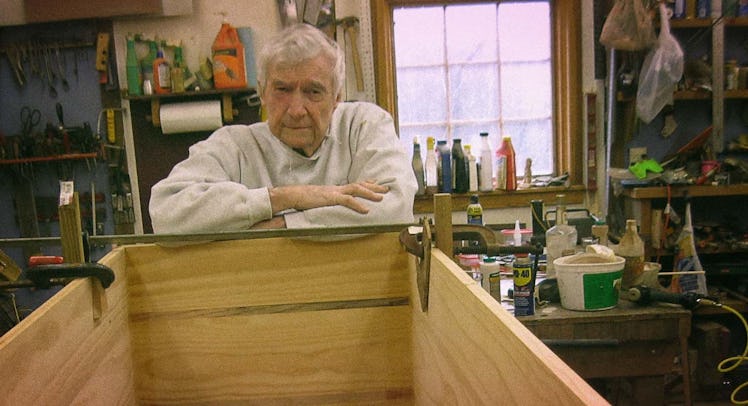

David Giffels keeps busy. Over the last decade, he’s authored a handful of memoirs, refurbished a condemned house he bought with his wife in Akron, Ohio, teaches in two prestigious creative writing programs, and recovered from his previous gig writing for MTV’s Beavis and Butthead. Also, he made a coffin for himself and for his father, a fraught experience he says taught him a lot about both mortality and family.

Furnishing Eternity: A Father, A Son, A Coffin and A Measure of Life is an affecting and morbid look at family relationships and how men spend their time. It covers the four years David and his father, who was well into his eighties, spent constructing and sanding and shiny their coffins. It also dwells on the death of David’s mother and his best friend. Death interrupted life and vice versa.

When I emailed David about an interview, he informed me politely that he’d have to delay our call because, just three days after the release of his book, his father had passed away. “I’m not uncomfortable talking about his death,” David wrote. “It’s a way to celebrate him.”

Ultimately, we didn’t talk about his father’s death — not exactly. We spoke about what he left behind and what he made.

What about the process of woodworking and building things fostered a bond between you and your father?

My dad was the traditional, not-real touchy-feely kind of dad. He was warm and loving, but he wasn’t one to hand out fatherly wisdom. I have countless memories from my childhood of sitting in his workshop while he was tinkering. He was an engineer — a classic Midwestern tinkerer.

My wife and I bought a nearly-condemned old house. He and I shared that experience of saving that house and rebuilding it. Our bond grew as I got older.

Why a coffin? Why not a table?

He and I have built a lot of things over a lifetime together. That’s always been the biggest part of the bond between us. The coffin thing stemmed from a longstanding quasi-argument between me and my wife. She’s half-Sicilian and a traditional Catholic. She comes from this very formal, traditional, impression of what a funeral should be. I’m also Catholic, but I think the whole funeral home thing is overdone and unnecessary. I joked that I didn’t want to be buried in a casket at all, that I just wanted to be buried in a cardboard box. She doubled down, saying, ‘You have to be buried in a formal, expensive casket because that’s how it’s done.’ That led to the idea that my dad and I, for much cheaper than commercial price, could build a coffin that would serve everybody’s needs.

How long did it take you to build the coffin?

It took about four years, but that’s because we spent as much time not working on it as working on it. I was writing about it and it became this thing that was supposed to be a meditation on mortality and life, but mortality actually got in the way.

After we started working on the coffin, my mom died unexpectedly and my best friend died a year later. Much of the book is about what it means to lose people and to grieve. My father lost his wife, but also took a really unusual command of his life. He was in his eighties and he didn’t say this overtly, but it was very clear that he was going to make the most of whatever years he had left. He was going on trips and accepting invitations. He was really busy living and I was trying to drag him back into this workshop to make a coffin. But I got busy too. Just the ebb and flow of life was dominating more than the ebb and flow of the construction project.

Where did he go when he was making the most of those years?

He served in the Army Corps of Engineers in Germany. He went back for the first time in 50 years to see the army base. He also visited a convent in Troyes, France. He had been helping raise money for the restoration of this cathedral that these nuns were involved with. He had never met them. He loved going to high school and college basketball and football games, especially with my two brothers, who are more into sports than I am.

Still, you stuck to it and ultimately finished not just one coffin, but two.

After we finished making my coffin, my dad turned to me and said, ‘Well, David, we made all the mistakes on this, so now I’m gonna build my own the right way.’ He started it right around this time last year. He was done by the end of spring.

Were the two caskets constructed very differently?

Mine is more formal. It’s a rectangular box-shape. It’s built with pine and oak. It has elaborate detailing in some of the moldings and so forth. That was all thanks to my dad. I was more of the apprentice on this job.

My father’s coffin is built from the cheapest pine he could get in the traditional coffin shape — the Barnabas Collins Coffin — with the angled sides. It’s very simple and it’s very elegant in a rustic way. I like it much better than my casket.

My father couldn’t put a straight rail down the side of his coffin for the handles because of the angle so he went on eBay and found a used set of a casket handles. I was like, ‘Dad, what do they mean, ‘Used?’ He was like, ‘Apparently, they exhumed a casket.’ He bought them for 15 dollars. That’s a very midwestern thing, too. To scavenge things and, to not waste anything, and to have enough sense of humor to use somebody’s else’s casket handles.

It seems like your dad had a really terrific sense of humor.

It’s funny. The book starts with me thinking of him as the oldest person I know. It ends with me thinking of him as the most alive person I know. I was writing this book as an obvious attempt to try to approach the theme of mortality, and then of course, mortality came in and blindsided me.

The last gift that my dad gave me was to show how important it is not to waste time, and to use your time for the things that you’re aware that you should be doing, but sometimes we don’t. We get mired down by a lot of things that aren’t the right things. He just really seemed to have this sort of enlightenment about what the right things are and to not turn down any chance to engage with those things.

Woodworking aside, what did you learn from your father as the two of you built coffins or, prior to that, when you renovated a house together?

My father left work for me so that I could do it under his watchful eye without him actively playing the teacher. He was really good at guiding but not taking things over. He wasn’t going to say, “Son, I’m going to give you a lesson now.” He wasn’t that kind of dad.

If there was one memory that could be emblematic of your father, what would it be?

Every two years, we took a big family vacation together on an island on Lake Michigan. We rented a house there together. This house was full of family and everybody’s kind of cutting loose. This house had a big, exposed ceiling with a heavy rough-hewn beam that ran across the open second story level. There was an open railing that went around the second floor. Everyone’s like, “Nobody is allowed to climb over that railing and walk across that beam.” My 80-something-year-old dad walks across this beam like a tightrope, acting like he’s going to fall.

Near the end, when he knew he was going to be dying, he said, ‘Dying doesn’t make me sad. The only thing that makes me sad is that it will make other people sad.’ That was his way of saying that anything that life had offered, he had grasped and had done.

This article was originally published on