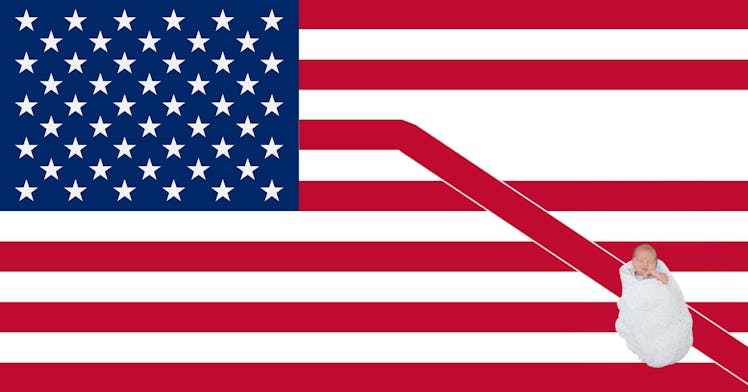

The Covid-19 Baby Boom Is a Lie.

Covid-19 is actually accelerating a decade-long decline in the American birth rate. And this will have long lasting effects on our country as we know it.

In the early days of the pandemic, jokes about a coronavirus baby boom abounded — surely all this enforced at-home togetherness would mean a jump in the birth rate and big bouncing new cohort of “quaranteens” around 2034, right? But a recent report from the Brookings Institute paints a very different picture: Covid-19 is actually accelerating a decade-long decline in the American birth rate. And this will have long lasting effects on our country as we know it.

Intense, transient events like blackouts and passing hurricanes can, anecdotally at least, result in a mini baby boom nine months later. But the uncertainty that pervades every aspect of life during an epidemic or a financial crisis almost invariably leads to a decline in fertility as families reassess their plans for the future.

In trying to gauge what the double blow of pandemic anxiety and economic hardship will mean for the birth rate, Brookings economists Melissa Kearney and Philip Levin analyzed data from two historic cataclysms: the Spanish Flu of 1918, which claimed some 675,000 American lives, and the Great Recession of 2007–2009. During the Spanish Flu, birth rates dropped dramatically whenever mortality spiked, almost perfectly mirroring each other. In the Great Recession, fertility was so highly correlated with unemployment that for every one percent rise in unemployment, they found a 1.4 percent drop in the birth rate. For us, in 2021, all those calculations add up to 300,000 to 500,000 fewer births. That’s on top of the steady decline we’ve seen since the Great Recession, with 400,000 to 500,000 fewer births annually.

Last year, with nearly half of all counties reporting more deaths than births, the United States hit its lowest growth in a century. Historically, population growth in the U.S. has been nourished and protected by a healthy influx of immigrants, who have settled and started families here. But immigration too has been at historic lows since the change in administration. (A recent Census report games out three different immigration scenarios — at zero immigration, American population growth sputters to a halt by 2035 and starts falling into decline.)

So what does it mean for the economy when there’s a dramatic drop in the birth rate?

“There’s a ripple impact,” says Kenneth M. Johnson, professor of sociology and senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire. Maternity wards are less busy, and in some cases have closed. And all the industries that cater to young children, from the makers of baby food and diapers to toy stores are affected. “There are fewer kindergarteners each year than there would’ve been, and that will ripple its way up eventually into colleges and universities, and ultimately into the labor force,” Johnson adds. And of course, when larger, older cohorts retire, the burden of supporting them will fall on an ever-smaller population of young working people.

If the pandemic stretches on and the economic situation worsens, those ripples will travel further and have more enduring effects on where we live, whether or not we have kids, and if we do, how we raise them.

“If after all these years of a lowered birth rate, the U.S. goes into a steeper fertility decline, now you’re talking about fewer babies for 15 years, maybe,” says Johnson. “You’re almost talking about a generation that will be smaller. That will have a ripple effect all the way up through the economy as it occurs. And it means that family formation is probably going to be slowed, and that couples will not marry as early or as much.”

The U.S. has never experienced anything like this. The closest thing to a change in family size of this magnitude, says Johnson, would’ve been the baby boom. When baby boomers came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s, they delayed having children, and “partially as a result, more women went to college and had more opportunities in the labor force,” he says. “That was a pretty substantial structural change in the United States.”

In the great pandemic, however, with families locked down together, those opportunity costs are affecting men as well. In the short term, families have reshaped themselves, as men and women both struggle to balance homeschooling children with working full-time. “Couples or partners are going to have to address these changing dynamics, not only in childbearing but in childrearing too,” says Johnson.

Birth and death rates aren’t the only forces shaping our population and family life. “We’ve already seen that immigration has been dramatically slowed,” says Johnson. “I mean, if you can’t even cross the Canadian-American border, imagine what it’s going to be like for anybody else trying to come to the United States. But what will it mean for migration within the United States?”

Before the coronavirus, states like Massachusetts and New York were losing population to states like North Carolina and Nevada. “So now here comes the great pandemic,” says Johnson, “what’s it going to do to migration patterns? Are people going to be more likely to stay in place? That has significant implications for different parts of the country in different parts of the economy.”

Some of those shifts are already happening, though only time will tell if they become permanent. A survey published this week by the Pew Research Foundation found that 22 percent of American adults had moved or knew of someone who had moved in response to the pandemic: That’s millions of Americans relocating because of the Covid-19 outbreak — college students returning home from closed campuses, elderly parents moving closer to (or in with) their adult children and grandchildren, and families leaving areas they deem less safe or can no longer afford after losing their income.

In the face of epidemiological and economic uncertainty, there’s a strong drive to hunker down in safety, to wait and see. But even for parents who have alternatives open to them, there are massively complicated trade-offs.

“The core cities may feel more stable,” notes Johnson, “they’ve got the big hospitals and access to more resources. On the other hand, if you’re worried about your children — where are they going to play, and what kind of space are you going to be in — that can make the suburbs and, in some cases, smaller places a little further out more attractive.”

“It’s going to be a very dynamic time with a lot of different things in motion,” says Johnson. “I’m sorry that so many demographic phenomena give us a chance to see change under such difficult circumstances, but these are the times when society is changing.”

This article was originally published on