What It Was Like to Be Raised by Evel Knievel

“My dad struggled with the idea of passing the baton to me. He saw me as one of the many competitors who were trying to out-jump him, but in reality I was his biggest fan.”

Evel Knievel, born Robert Craig Knievel, 1938 in Butte, Montana, was an American daredevil. Known for his iconic white leather jumpsuit, between 1965 and 1980, he attempted more than 75 ramp-to-ramp motorcycle jumps over ever more challenging obstacles. For decades he held world records for the most cars and buses ever jumped on a motorcycle. Many of his televised stunts were among the most-watched sporting events of all time, leading to international fame and a popular toy line. Holding the world record for the most bones broken in a lifetime (433), Knievel also became known for his spectacular crashes, including a failed jump of the Caesars Palace fountains in Las Vegas and an attempted jump of Snake River Canyon in Idaho in which his rocket-powered cycle malfunctioned, prematurely deploying his safety parachute. A father of four, Knievel died of pulmonary disease in Clearwater, Florida, in 2007.

The first memory I have of my father was from afar. I was very young and I remember sitting in the stands with my mother at Ascot Park, a speedway outside of Los Angeles, gazing at the blurs of motorcycles speeding past and asking, “Which one is Dad?” “He’s in last, in the black and yellow,” she said. I wanted to be closer, to get in on the action. That came soon enough. When my father would crash and hurt himself during a jump attempt, he’d call us kids into the ambulance with him. “Look at me,” he’d say to us. “Promise me you won’t do what I do.”

My father had the stern attitude of a drill sergeant. Of the four of us kids, he disciplined me the most, since I was the rebel. I was the one constantly challenging him and emulating him. My first bike was a Honda 50 mini bike. To teach me to ride, my father put me and my brother in a ditch with our bikes and tied a rope around us. If we got scared and accidentally twisted the throttle too far, he’d yank us off the bike before we got hurt. He made us always wear helmets and told us to never go riding alone.

But pretty soon I was putting up a sign on our gate reading “See Evel Knievel Junior jump for 25 cents.” Then I’d jump my mini bike over ten 10-speed bicycles. My dad would flip out when I’d get banged up riding in the mountains, tearing up my knees or breaking my arm. But since he realized I wasn’t going to stop, he decided to put me into his show, so he could watch over me. It was great. At age 8, I performed my first show with him at Madison Square Garden. Then I went on tour with him, doing wheelie shows before his big jumps, where I rode around on my back tire for the crowds. Soon I had my own action figure as part of the Evel Knievel toy line. We traveled all over the United States, as well as to Puerto Rico and Australia. When I was 14 or so, he’d let me drive his 62-foot “Big Red” flatbed trailer, with his name on the side and filled with his bikes and touring equipment. We’d rumble down the highway as truckers would call out over the CB radio, “There goes Evel!”

But the good times didn’t last. As a teenager, I argued a lot with my dad and got in some trouble, spending some time living away from home. At age 19, I moved out for good and embarked my solo career. My dad struggled with the idea of passing the baton to me. He saw me as one of the many competitors who were trying to out-jump him, but in reality I was his biggest fan. Still, even during our time apart, his lessons stayed with me. “Quit drinking” he’d tell me. “Don’t do as I do, do as I say.” And before one of my first big jumps, over 10 vans, I became so anxious that I developed a fever, but then I remembered what he always told me. “It’s normal for you to be nervous,” he’d say, adding, “The bigger the crowd, the better you’ll do.”

He’d hear from folks about how good I had become, but that never stopped him from worrying about me. When we’d talk on the phone, he’d ask me, “Are you using a safety deck?” and “Is your bike running right?” He’d seen other guys emulate him and end up paralyzed or killed, and I think he worried that if that ever happened to me, it would be on him.

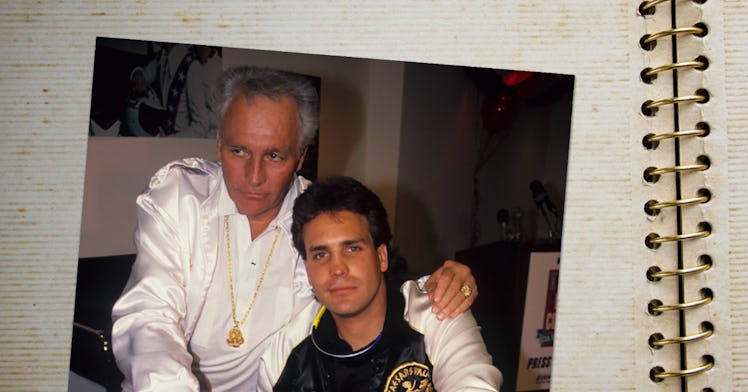

In 1989, when I jumped the Caesars Palace fountains that he’d failed to clear 22 years earlier, he was there with me. When I made the jump and said, “That was for you, Dad,” he ran up and hugged me with tears in his eyes. I had never seen him so emotional.

After that, he supported me throughout the rest of my career. Now he was the one who’d pump up the crowds with wheelie shows before my big stunts. I went on to jump between two 13-story buildings, over an oncoming locomotive, even over the Grand Canyon. In the end, I did many more jumps than my father ever did. As I always tell people, “I go twice as high, twice as far, but I hit the pavement twice as hard.” Like my father, I suffered numerous broken bones, many difficult surgeries, and several crushed vertebrae. I am lucky I am still able to walk.

During the last few years of my father’s life, we spent a lot of time together. We reminisced about the crazy lives we’d lived, and how lucky we’d been time and time again. I’d say to him, “I love you, Dad,” and he’d tell me, “I love you, too, Rob.”

Robert Edward Knievel III, a.k.a. Kaptain Robbie Knievel, is a celebrated stunt performer. During his 30-year career, he accomplished more than 350 jumps, set 20 world records, and is among the greatest daredevils that ever lived. He will soon be releasing his autobiography, Knievelution: Son of Evel, as well as starring in a feature film, Blood Red Snow.

This article was originally published on