The Family Separation Crisis Isn’t Over for Black Parents

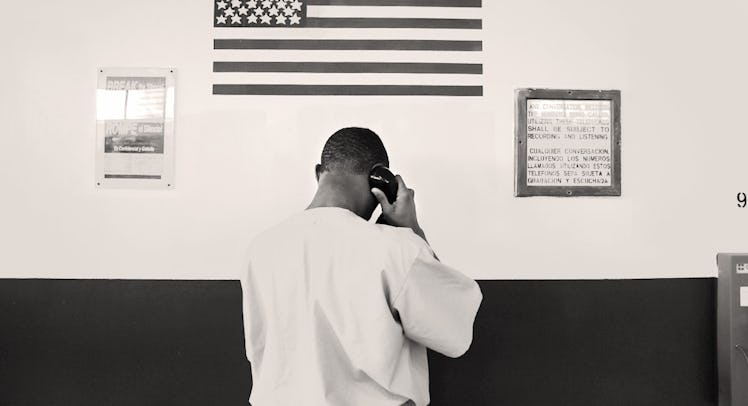

Media and politicians are focusing on immigrant kids separated from parents, but black kids have been facing a similar crisis for decades thanks to incarceration.

One in every nine black children in America has a parent in jail. It’s a shocking statistic that has become ever-more shocking as incarceration rates have climbed. Even as President Trump announced an end to his administration’s so-called “Zero Tolerance” immigration policy, which separated children from parents at the border and shocked much of the country, the number of black children separated from their fathers and mothers is on the rise. And, yes, policies pushed by Attorney General Jeff Sessions are likely to exacerbate the problem. Still, the public outcry remains muted.

Of the estimated 70 million children growing up in America right now, some 5 million have had a parent in prison. And these children are increasingly finding their way into the child welfare system. Between 2012 and 2016, the number of children removed from their homes in the wake of sexual abuse, physical abuse, abandonment, and caretaker death decrease. The number of children removed from their homes in the wake of a parent’s incarceration went up by 5.6 percent.

The suffering is heavily correlated with race. Six percent of white children have had a parent in prison compared to 11.5 percent of black children, meaning it’s about twice as likely for a black kid to have a parent behind bars. It’s no wonder: A full 40 percent of the prison population is black, despite representing only 13-percent of the population of the United States. Why are they there? One in five inmates were incarcerated due to a drug offense, most likely possession (there were six times more arrests for possession between 1980 and 2015 than there were for drug sales). Prison are disproportionately black because black people are disproportionately arrested for drug crimes and disproportionately jailed for them.

And it’s not as if black parents are more likely to be criminals than any other parent. Rather, the judicial system has been rigged against them. Consider the crack epidemic of the 1990s when mandatory sentencing guidelines for possession of crack cocaine were put in place. Sentencing guidelines required that a conviction of distributing 5-grams of crack carry a 5-year minimum federal prison sentence. Meanwhile, to receive the same sentence for the no-less dangerous powdered cocaine, a defendant would have to distribute 500 grams. Whites accounted for just 7 percent of defendants in crack cases, despite accounting for 66 percent of crack users at the time. Blacks, on the other hand, accounted for 80 percent of defendants in crack cocaine cases despite being far less likely to use crack cocaine. The black defendants were also likely to be non-violent, low-level offenders.

Since that time there have been some sentencing reforms, but judges still have the discretion to increase or reduce certain sentences. One recent study found that for the exact same crime, blacks are still likely to see a 19-percent longer sentence than whites. And that’s at the end of a long chain of unequal justice. Black neighborhoods are more likely to be policed than white neighborhoods. Blacks are more likely to be profiled and pulled over for minor traffic violations. They are also more likely to be held in jail prior to trial rather than being released. And it all means that there are more black children with a parent behind bars.

The number of black children separated from their non-violent parents has received some press attention — more than the normal minimum after the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement — but the country has not worked itself into a social media lather and Congress has done little. That’s true despite the fact that young children are disproportionately affected by this rolling crisis. Some 41-percent of all children in out-of-home care in the system are under the age of 5 — or the “tender care” years, as the government might say.

And it’s not as if family separations for reasons other than immigration are somehow less devastating to a child’s outcomes. Researchers define separation from a parent due to incarceration as an “adverse childhood experience” because of the stress and trauma it produces. Other ACEs include witnessing domestic violence, living with someone who is mentally ill or suicidal, parental divorce and living with someone that has a history of substance abuse. The stress and trauma of ACEs can have devastating consequences that include mental illness, addiction, criminal activity, behavioral problems in school, and poverty.

Parental incarceration often leads to a child experiencing more ACEs, creating a cumulative traumatic effect. So, where are the hue and cry? Why, outside of black-led protest groups and their allies, are there not calls for an immediate end to the crisis?

The most obvious reason as that there’s no simple solution. Because the separations at the border were a product of Trump policy rather than a law, it was relatively easy for the President to, having caved to public pressure, put an end to the program. But parents are incarcerated for a number of reasons — most entirely legal. They are caught up in a system rather than a program. Systems change incrementally — the criminal justice system doubly so. (It doesn’t help that for-profit prisons have a healthy lobbying presence in D.C.).

Millions have greeted the end of the family separation at the border as a necessary victory. What is clear, looking at the statistics, is that it’s just one victory and that, to ensure the wellbeing of children, more is needed. Unless change comes to the justice system, children will continue to be needlessly separated from their parents by the American government.

This article was originally published on