What It Was Like Having ‘Doonesbury’ Creator Garry Trudeau for a Father

“He was an affectionate man, an enthusiastic roughhouser, and capable of unabashed silliness. But inside the studio, he seemed to me perceptibly more solemn, more focused, more staid.”

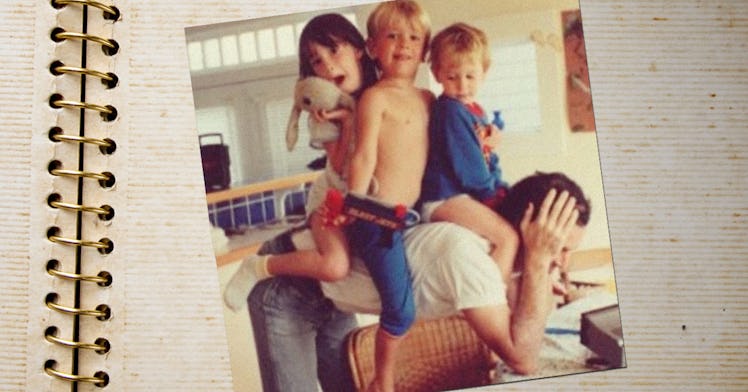

Garry Trudeau, born Garretson Beekman Trudeau in 1948, is the creator of the comic strip Doonesbury. He was born in New York City and raised in Saranac Lake, in upstate New York. Doonesbury grew out of a comic Trudeau created while attending Yale University, called Bull Tales. In 1975, he became the first cartoon strip artist to win a Pulitzer Prize for his work. Today Doonesbury continues to be one of the most popular comic strips in America. Trudeau has also written and produced films and television shows including Tanner ’88 and the political satire Alpha House. He married journalist Jane Pauley in 1980 and has three children: Ross, Thomas, and Rachel.

Next to the door of my father’s studio stood a lacquered mahogany grandfather clock that didn’t work. It faced down a hall that ran the length of our 10th-floor apartment in New York. If the studio door was closed, I would sometimes open the clock’s cabinet door and set its brass pendulum swinging, producing a resonant tick-tock that softened as gravity took its course.

“Tick-tock knock-knock.”

“Just a minute, Rossy.”

Dad only ever seemed to shut the studio door on Fridays. His slate of six dailies and one nine-panel Sunday strip were due to the inker by 6:00 p.m., and he rarely finished a minute before. And just as his professional anxiety reached its weekly zenith, we three children would burst back into the pre-war Central Park West co-op with typical weekend-anticipatory zeal. The few times my father could have been said to have snapped at me unfairly occurred at the threshold of his studio, in mid-afternoon on a Friday: deadline day (or, as my sister called it, “Daddy’s Mad Day”).

While it was by no means off-limits, the studio was a serious place, and held an appeal that, for most of my childhood, defied naming. For although it was a space for hard work and sustained concentration, it was at the same time filled to bursting with objects that looked for all the world like toys: Framed, full-color Little Nemo and Krazy Kat originals; a carved wooden Dan Quayle figurine that ejected an erect penis when you picked it up; a hand-carved didgeridoo; a life-size papier-mâché sculpture of Mike Doonesbury’s head and torso; USO press lanyards from Iraq and Kuwait; amorphous, gummy wads of gray eraser material that went white and shredded like dough when you stretched them out.

The studio had the power to subtly transform my father. He was an affectionate man, an enthusiastic roughhouser, and capable of unabashed silliness. But inside the studio, he seemed to me perceptibly more solemn, more focused, more staid. More like Grandpa.

Dr. Frank B. Trudeau was a Columbia-trained country physician, a committed outdoorsman, and a decorated veteran of a U.S. Navy sub-chaser. He was reserved, but not aloof. Patrician, but not domineering. Above all things he valued honesty, respect, and integrity. And like my father’s studio would years later, Grandpa’s study in the Saranac Lake house where he raised his family served as a neat metonymy for the man.

The walls displayed a prized brook trout caught in Quebec, barometers and thermometers that he consulted daily, a painting of an Adirondack mountainscape. There were built-in shelves filled with boxes of delicate trout flies, and twin unsecured gun closets with a dozen hunting rifles between them. (Grandpa taught my father to shoot, clean, and oil a .22 at age 8, but refused to ever buy him a BB gun on the grounds that his son might treat it like a toy.) There was a flip-top desk and a low wooden coffee table with a bowl filled with Olympic pins from his time as U.S. Olympic ski team doctor at the Lake Placid Games. And at the center of the room in front of the small fireplace was a green leather armchair, where every night Frank would dictate his medical notes into a Bell Dictaphone.

As a child, during family visits to Saranac, I steered well clear of Grandpa’s study. My siblings and I were frightened by the alien solemnity of that room where everything smelled of Royal Yacht pipe tobacco. But to get to the guest bedroom where our parents slept, I had to summon the courage to pass through Grandpa’s study, and hope he wasn’t reading in his green chair. Though Grandpa never had anything but a broad smile for his grandchildren, disturbing him in his home office still felt abstractly profane. Here was a man whom my father still sometimes referred to as “sir,” who was inevitably stopped for several embraces and handshakes when we went to Donnelly’s for ice cream or to the tackle store before a fishing trip.

Grandpa’s own grandfather, Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, had moved to the Adirondacks in 1873 to take the “rest cure” after contracting tuberculosis. When he recovered he remained in Saranac Lake, and in 1894 founded a TB sanatorium and the country’s first laboratory for the study of the disease. (One of his early patients was Robert Louis Stevenson, who after his recovery gifted E.L. Trudeau his collected works; the copy of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde bore the inscription, “With Trudeau these months at my side, I never caught a glimpse of Hyde.”) Both E.L. Trudeau’s son and grandson, Francis Sr. and Jr., would become doctors themselves. Francis Sr. eventually succeeded him as president of the sanatorium, and Frank Jr., my grandpa, stewarded it into its present-day incarnation as the Trudeau Institute, an independent immunology and infectious disease research center. While my father would himself become an active trustee of the Institute, he would be the first Trudeau man in five generations not to take a medical degree.

While my father’s studio shared little aesthetically with his father’s study, both rooms inspired in me a reverential awe. Whether looking up at grandpa’s medical volumes or at the Time covers above my father’s sofa, I was filled with a similar dull dread that I would never know enough to be a man.

If I ever made a serious mistake — lied, or failed to keep my word — I might hear my mother say, “Your father would like to see you in his studio.” Punishment for fighting with my little brother or kicking my twin sister could be meted out on the spot. But lessons of character were taught in the studio.

When I was 10, dad called me into his office after I had been caught in a lie about an antique teacup I had broken and then hidden. I sat in his artist’s chair, teary and chastened and swiveling, staring at the indentations in the carpet where the wheels usually came to rest under his drawing board. “Things can be replaced, Ross. Hey, look at me.” My father fixed me with the same eyes that I have and that his father had before him: downward sloping at the temples, slightly hooded, suggesting melancholy or weariness. “We can glue this cup back together. But your reputation is more fragile and harder to fix. You only get one reputation.”

When we had such serious studio talks, part of the enduring shame I felt at disappointing my father stemmed from the old-fashioned-sounding language he used. There amongst his Maoist propaganda pins, artifacts of the counter-culture, and a poster of semi-stoned Zonker Harris, he would talk to me about reputation, and honor, and “a man’s word.” I wouldn’t have been able to articulate it at the time, but I understood him to be using a language passed down to him from his father.

The first time I can ever remember seeing my father cry is when he eulogized my grandfather at St. John in the Wilderness at Lake Clear. It was 1995. Frank had died after a year long struggle with amyloidosis, though struggle isn’t perhaps the right word. In the year after his diagnosis, he was rarely in his study. Rather he took to the slow rivers of Montana to go fly-fishing and sailed the 20-foot boat he kept anchored off St. John’s in the U.S. Virgin Islands. My last glimpse of him was waving from the wharf off Cruz Bay.

At his funeral, Dad spoke about how Grandpa was immune to fashion, wearing the same clothes he had in college through his adult life. He remembered how his father had been touched by hours of spontaneous speeches of gratitude at a retirement dinner, but how his only regret was that the speeches had focused almost entirely on his contributions to the Institute, rather than his 40 years as a physician meeting the day-to-day health needs of his community of 7,000 in Saranac Lake. For decades, seven days a week with a break on Wednesday evenings, Frank was on call. Frank was there.

After Grandpa was interred in the family plot — next to generations of his forebearers going back to E.L. Trudeau — Dad brought just one token from Frank’s study with him: a desk name block from his days as an aide to a Navy Admiral.

While the simple wooden object never needed any explanation, it took years and years over the course of my childhood for the other eclectic artifacts in my father’s studio to slowly come into focus. Dad never volunteered much information about the tchotchkes that lined his studio. I was well into my 20s when, while looking up at a portrait of Hunter S. Thompson, it occurred to me to ask if Dad had ever met the man he’d lampooned for decades. Dad said that no, he hadn’t, but he’d once received a package from Thompson filled with used toiled paper. I stood blinking at him, mouth open. He smiled and shrugged. I was 30 when I first commented on a pair of silkscreened portraits of him from the ’70s — you can tell from his beard and the leather cap — saying how much I liked them and didn’t they look a lot like Warhols? Dad exhaled, tossing some junk mail in the wastebasket without turning around, and said that they were, in fact, original Warhols.

“No way. Stop it,” I said.

“Well,” Dad said, “he wasn’t such a big deal back in those days.”

My father says he has no interest in ever writing a memoir, claiming with apparent sincerity that he doesn’t think anyone would be interested in reading the stories behind the artifacts of his life. Are these things meaningful to him? Do they remind him, keep him company? Why do I, now a man myself, feel compelled to catalogue them on his behalf? It’s impossible not to wonder which of these objects might eventually end up on my desk or on the walls of my own home. Or perhaps I won’t bring an object with me at all, just the memory of the soft echo of a grandfather clock in the hall. Tick-tock. Knock-knock.

Ross Trudeau is a crossword puzzle creator whose work is frequently published in the New York Times.

This article was originally published on