The Cursed History of Jell-O and the Family Behind the Gelatin

As a new family history of the jigglin' gelatin explores, there's a lot more to Jell-O than meets the mold.

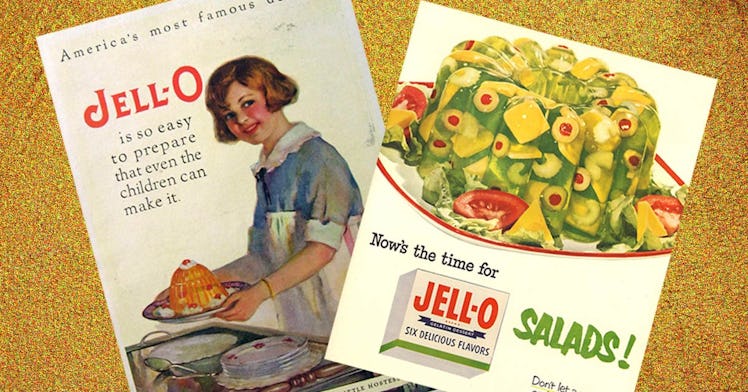

Jell-O, the glistening, jiggling gelatin is a classic dessert, one that, since its inception, has been a mainstay on the tables and in the pantries of typical American families. There were the Jell-O molds, the Jell-O jigglers, the sugar-free Jell-O cups, the savory Jell-O salads and tiered gelatin centerpieces popularized in the mid-century that were mixed with mayonnaise or encased cuts of meat. It has been a side on kid’s menus, a lunch companion, and an allowed indulgence for women who diet. Its ascension and shift was throttled by second-wave feminism. Throughout its life, Jell-O brought a lot of families joy.

But for the family behind the brand, it brought something else. In her new book, Jell-O Girls, Allie Rowbottom, whose great-great-great-uncle purchased Jell-O in 1899 from its down-on-his-luck creator for $450, charts the rise and fall of the beloved food with that of her family. She writes of the “Jell-O Curse”, which derived from the fact that so many of the men in her family met untimely ends due to struggles with alcohol or suicide, but really applies to the curse of expectations laid down upon the women of the family — and many other women — from Jell-O’s marketing. and which caused her to understand the history of Jell-O and what it meant for the women. The result is a compelling look at family, feminism, and a company all Americans know well but don’t know well enough. We spoke to Rowbottom about Jell-O’s humble beginnings and many different permutations, the Jello “curse,” and how Jell-O is a much larger emblem.

Where did Jell-O’s history begin in the United States?

The guy who came up with the recipe really got a raw deal. He was struggling. He was trying to make ends meet as a patent medicine maker, and he just couldn’t leverage Jell-O. He sold it for $450 to my great-great-great uncle Orator Francis Woodward in 1899, which is like $4,000 in today’s terms. It turned out, 25 years later, when the Woodwards did sell Jell-O, it was for 67 million dollars. It was one of the most profitable business deals in American history. For a man to invent that product — he didn’t even see any of that money.

There’s something so interesting in the way that Jell-O’s place on the American table has shifted over time. It almost mirrors, to me, a sense of an American identity.

Jell-O is nothing if not a versatile product. Not to be cliché, but it’s molded itself to every cultural moment. It only struggled when second-wave feminism really gained foothold. Women started leaving their husbands. That was a real turning point for Jell-O, marketing and identity-wise.

Prior to that, it was an efficient, cheap stretcher. Gelatin was a product that was the purview of the extremely wealthy because it took so long to make. So Jell-O was a convenient, cheap, scientific wonder in an era where people were really drawn to convenient, scientific food. The natural world was being eschewed in favor of science-based products, of processed foods. Before the war ended, during rationing, you could hide unsightly leftovers in a Jell-O mold. In the ’50s, the era of abundance, there was still a push to encapsulate food and make everything clean, neat, and tidy, as to disguise ingredients that were nutritious. Hence vegetables being hidden in Jell-O and slathered in mayonnaise.

Your story deals with the so-called “Jell-O curse,” which your mom heard about as a child. It pertains to the fact that so many of the men in your family died early deaths. Do you believe in the curse?

The curse was always metaphoric to me. Do I think it was literally true? No. But I do think that my family thought that they were particularly afflicted by misfortune. My mom, hearing about the curse as a child, looked at her surroundings and said, ‘Well, that makes sense to me.’ She watched people in her family suffer and die early deaths. Trying to square the suffering she saw amongst the women in her immediate circle, I think, was something that stayed with her for a really long time. It wasn’t until she was an adult that she started to identify the curse on her own terms. The curse was not specific to her family. It was an affliction that influenced and oppressed all women.

Your mother was having revelations about feminism while Jell-O, the reason for her wealth, was being packaged and sold to the American family — particularly housewives.

Yes. Until the late ’90s, there were really no men featured in Jell-O advertising as anything but consumers of Jell-O. If they were on the ad, they were being served to. Women were the ones who prepared it. They used Jell-O as a tool by which to manipulate men or service their children. They also potentially diminished themselves by using Jell-O as a diet, too. Jell-O served as a particular emblem of American cultural values. That emblem was that women were of service, and that was our primary role.

I’ve read a more than a few ‘70s era cookbooks, and read one that said that any good wife has a Jell-O mold in her first home with her husband.

Oh yeah. It was overt.

Well, Jell-O — and the old school mold — haven’t disappeared. They’re still alive and well.

It’s an art form. A friend of mine from the Midwest is really adept at making elaborate molds. It is so challenging. People do crazy stuff with Jell-O. I didn’t appreciate that fully until I tried to make one of them myself and like, failed, miserably. It was hard work.

Jell-O is such a nostalgia item. You see all those internet lists — all those ’50s recipes. We have some sort of strange schadenfreude looking back at what people ate at certain times in history. Jell-O is unbelievable in some ways, but also kind of fascinating and grotesque and titillating at the same time. People were putting tuna in lime Jell-O and calling it a day.

When did Jell-O stop becoming this adult dinner food and start becoming a food for kids?

Jell-O struggled to market itself to women in the ’70s, right when women started leaving their husbands. Honestly, that struggle took place over a long period of time. But when they brought in Bill Cosby, I think, in the mid-’80s, it was to orchestrate this shift from Jell-O as a dessert or a salad ingredient to Jell-O as a snack.

So feminism won the Jell-O war?

Women were in the workplace. They weren’t staying at home making Jell-O molds. It was marketed as a snack for children. Executives wanted to convince moms that this is a thing that they could make, keep it in the fridge, and throw it in a Ziploc bag. But today, the actual moneymaker in Jell-O is in sugar-free pre-made puddings and sugar-free pre-made Jell-O cups. Those are really popular with Weight Watchers people because it’s like a zero-point food. You can eat it with abandon. It’s an “allowed indulgence.”

How do you actually “feel” about Jell-O?

You know, I feel neutral towards it, really. I have Jell-O money in my bank account. I am not “anti-Jell-O.” I don’t think it’s the best thing in the world either. But my main area of interest is Jell-O as the larger emblem, which is obviously what I try to unpack as I was doing this book, probably to excess.

I think my mom sort of felt that way towards it as well, towards the end of her life. Earlier in her relationship to Jell-O, she found it gross. But towards the end, she was eating a lot of Jell-O, because she was sick and that’s what you eat when you’re sick. She accepted it. I didn’t grow up in Leroy, New York like she did. It’s a town that’s tied to it because of Jell-O’s history and legacy. It always felt distant to me. To her, it was so much more pressing. And so much more of a presence.

This article was originally published on