Maternal Gatekeeping and the Totally Accidental Rise of Overbearing Mothers

Andrea micromanages her husband. Was that always her plan? No. Does she want to? No. It's just something that happens.

Andrea had a full-time job, so her partner, Robert, stayed home with their young son. Each day, before the other two woke up, she went around the house preparing herself for her day and them for theirs. She filled sippy cups with milk; she prepped her son’s food; she chose specific toys for playtime and puts them in specific locations to be found. When she was satisfied, she would wake Robert to let him know that his shift has begun then head off to work. She would call during the day ensure that all was going according to plan. Her plan.

Andrea and Robert were — and are — real people, though those aren’t their names. They were anonymized as participants in a 2012 study conducted by Orlee Hauser, a sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. The point of that research? Documenting the phenomenon of “Maternal Gatekeeping,” the tendency of some mothers to insist on mediating fathers’ access to children. Though the term makes it sound like a way to understand the ways in which women keep men at a remove, it’s bigger than that, encompassing the idea of control and encouragement.

Andrea’s was most extreme case of maternal gatekeeping among the 40 couples Hauser interviewed. She micromanaged the details of her son’s days with Robert from afar. Was it always supposed to end up that way? Likely not. These dynamics tend to arise organically over time despite being bad for all those involved — think of Andrea’s stress and Robert’s powerlessness. Specifically, these dynamics tend to arise in heterosexual, white, middle-class households where both parents contribute financially. This is not to say that other sorts of families can’t engender this power structure, just that the focus of study has been on caucasian middle-earners, who may, for cultural or social reasons, be more likely to fall into specific patterns.

“The woman ends up doing more work, the child doesn’t get access to both parents, and the father gets ripped off of forming those special bonds that come with all of that dirty diaper stuff,” said Hauser.

The concept of maternal gatekeeping has been floating around social science literature since the 1980s, and was popularized by a 1999 study by Sarah Allen and Alan Hawkins of Brigham Young University. The literature on gatekeeping suggests that moms have some influence on fathers’ levels of involvement with kids, but this is just one of many, many factors. The Allen and Hawkins study found that 21 percent of moms in their sample of 622 were gatekeeping to an extent that limited dad’s involvement with the kids. But of course it’s a continuum. Mildly negative gatekeeping behaviors manifest occasionally in most co-parenting situations, and extreme, toxic situations are the exception.

This would all be a lot easier to understand if mothers’ commitments to traditional gender roles were predictive of the extent of their gatekeeping behaviors, but that’s not really the case. A 2015 study by Sarah Schoppe-Sullivan and others found that gatekeepers are not primarily driven by a belief that women should manage childcare, but rather by perfectionism when it comes to parenting.

“It’s this deadly combination where the mother has really, really high standards,” Schoppe-Sullivan, a professor of human sciences at Ohio State University told Fatherly. “She thinks she’s a really good parent, but she’s maybe not so sure about the dad. And the dad’s not so sure about himself.”

This means that gatekeeping is a product of both the way mom thinks and the way dad thinks. Mom believes there’s a right way and a wrong way to parent, and that her way is the right way. When dad does things his way, mom responds with attempts to control him or just do it all herself. Dad feels maybe a little miffed, but also perhaps a little relieved of all that responsibility (or deeply suspicious of his own competence). He may feel that ultimately mom knows best, or that he has little power to negotiate the situation. For whatever reason, he largely acquiesces and the patterns of behavior reinforce themselves.

This is not just about a relationship between a man and a woman and their kids. Gatekeeping is informed by a culture that still judges women harshly on their ability to be perfect caretakers, while judging fathers more so on their ability to make a living to provide for their family. It can feel easier to slip into the roles society makes for us, particularly in those terrifying first years as a parent.

But gatekeeping is worth fighting against. A growing body of evidence suggests that kids do better in just about every aspect of life when they have committed, involved fathers. Much of this research on the “Father Effect” shows that any loving second parent helps. There’s also some evidence that fathers may be able to offer kids special benefits, for example through exposure to rough-and-tumble play, which is more likely to come from dad than from mom.

Gatekeeping behaviors are learned, not innate. Both men and women are capable of gatekeeping, and if there’s a genetic component, it would at best incline certain people to it, not cause it.

“I’m not going to say that there couldn’t be some hardwired parts that would maybe predispose mothers in particular, say, in the first months of parenthood, to feel maybe especially protective of their infants,” Schoppe-Sullivan says. “But do I think the actual gatekeeping behavior is hardwired? No. And the way that men and women are socialized in societies like ours, I would give that, ultimately, greater weight.”

Ongoing research around the world may help tease apart the cultural impact on gatekeeping. Liat Kulik, a professor of social work at Bar-Ilan University has studied the phenomenon as it exists in Israel. She said in an email to Fatherly that, although comparative research has not been conducted, in her view gatekeeping manifests in Israel in similar ways as in other modern societies. She pointed out that, for maternal gatekeeping to be a meaningful concept, it must exist in a society where fathers seek influence in the parenting and domestic spheres.

There’s hope for men who want to be more involved with their kids but feel shut out. Moms who gatekeep often don’t know they’re doing it, and often wish they had more help with the kids. Although they gain some things by gatekeeping — such as power, control, a sense that they are a supermom who can do it all — they seem to lose more. The research shows that gatekeepers do more work, have higher levels of depression and anxiety, and have poorer romantic relationships than those that collaborate with their partner.

“Sometimes fathers think that just because a mother is gatekeeping means that she wants to be,” says Daniel Puhlman, a professor of family science at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Puhlman recently authored an article establishing an empirical scale to measure gatekeeping behavior. In his previous job as a clinical family therapist, he learned of gatekeeping and its consequences to families and relationships first hand.

If he could get the dad to buy into the process of therapy and speak up about his wishes and concerns, the mom would typically listen, and respond “Moms would change; they would evolve,” says Puhlman. “I think it credits them with the desire to have that happen.”

Simply identifying the problem can go a long way, and talking about can go a lot farther. In cases where that doesn’t work, family therapy is an option.

In all of Hauser’s interviews on the topic of maternal gatekeeping, she never heard from a father who actively resisted it. One mom, however, did. “One day she realized, ‘Boy there’s so much pressure on me to do all of these things, and it would be so much easier if I just let it go, and let him be a dad. I trust this guy; I married this guy for a reason, and, at the end of the day, he really can do it just as well as I can, and who cares if the kid’s wearing red socks instead of yellow socks? Why don’t you just get over it?’ And she did.”

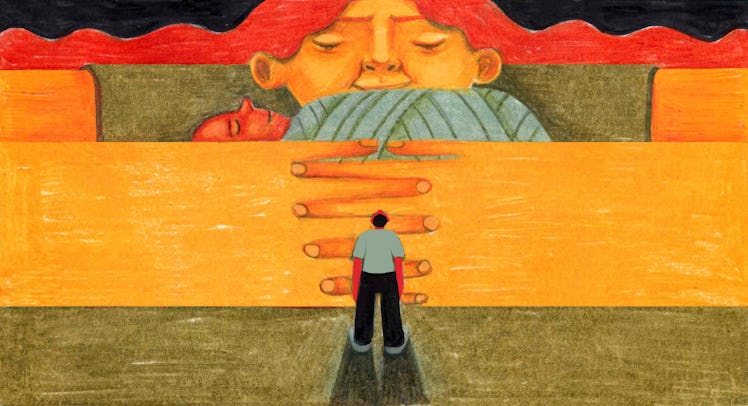

Illustrated by Hannah Perry for Fatherly.

This article was originally published on