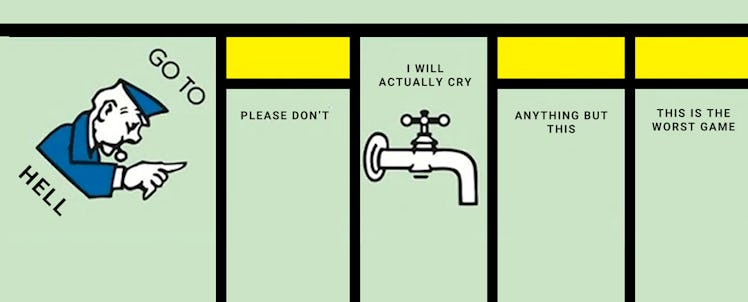

Monopoly Is the Worst. Why Do We All Still Play It?

The board game, which is celebrating its 85th anniversary this year, still sits atop the family board game pyramid. Why won't the madness end?

The first and only time I played Monopoly with my wife, the game ended with a board-flip. About an hour into the game, I landed on Marvin Gardens, a property that would’ve finally given her a belated monopoly. I was unwilling to consider any of her offers for the $24 rental and was content bleeding her dry with my glittering hotel on Park Place. She stood up, screamed profanity, and flipped the board over, sending plastic houses and paper money flying.

The twist comes after the rising action. My wife is a calm, patient person. She works with little kids all day. She rarely yells or picks a fight. Few things ruffle her. That Monopoly falls into that category speaks more to the game’s astonishing ability to sow seeds of discord than to her temperament. After all, she’s not alone in having lost it over the yellow properties. Every family has their own Monopoly story that is spoken in hushed tones. These stories all follow the same arc: We decided to play Monopoly, we started to regret it, we didn’t speak again until grandpa’s funeral. In 2011, a grandmother in the U.K stabbed her boyfriend for cheating during a game. I got off easy.

Monopoly, which is celebrating its 85th anniversary this year, has, thanks to a particular combination of nostalgia, laziness, and market power, enjoyed a place atop the family board game pyramid for decades. It’s still seen as the family game night game. But why? Why does Monopoly, which has an average (and generous) Board Game Geek rating of 4.4/10, persist? Why does everyone think they need to play this horrible game?

When will the madness end?

Monopoly is, at face value, clever. The game pieces are fun and nostalgic. (The thimble rocks). The community chest cards are whimsical (Bank Error in my favor? Hell yeah, I’ll accept $200!). But Monopoly is not a game of skill; from a mathematical perspective, no amount of skill can make up for bad rolls. It’s billed as a trading game, but trades are almost never a good idea; properties vary too highly in value and money is all but worthless over the long term. If one player scores some choice properties early, the rest of the game is just the other players bleeding cash — a frustrating and purposeless waste of time. Sure, Free Parking could change fortunes, but rarely over the long term. Mostly it serves to make losing an even longer and more grueling process.

Called The Landlord’s Game, the earliest form of Monopoly debuted in 1904 as a piece of anti-capitalist agit prop authored by Elizabeth Magie, a strident anti-monopolist. The game was designed to teach players about how rent screws over working people. It featured deeds and properties and the borrowing of money. There were railroads and a “Go to Jail” sign. It had a repeating, non-linear board. It also had two sets of well thought out rules: an anti-monopolist set and a monopolist set.

In a sense, Magie was seeking to illustrate the way that free markets reward advantage over capital over labor. That the game’s anniversary lines up with Bernie Sanders’s big run at the White House feels in some way fitting. His campaign shares an ethos with the original project — but definitely not with the current iteration.

Slowly, the game became popular, first with economists and students, and then with small communities who got wind of the game and customized it with properties plucked from their own neighborhoods. The story is more complicated than this but at some point an Atlantic City version of the game made its way to a man named Charles Darrow, who saw a business opportunity and brought it to Parker Brothers. Magie made $500 off her creation and zero royalties. Darrow made millions and, in some ways, Magie’s point.

The catch was and remains that Monopoly isn’t supposed to be fun. It was — and still is — intended to emphasize how random luck can make one person succeed over everyone else. Players who get ahead in the beginning only get further and further away as the game goes on. This has nothing to do with cleverness and everything to do with capital. Money accumulates. So, too, do frustrations.

Regardless, Monopoly remains an unavoidable part of the family game landscape. Year in and year out, it’s one of Hasbro’s biggest profit-makers. There are somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 versions, leveraging intellectual properties that range from The Simpsons and Game of Thrones to Stranger Things and Betty Boop. Included in that mix are editions branded after cities, sports teams, and abstract concepts.

The iterating doesn’t end. Each new year comes with its own new editions primed to capitalize on cultural moments or obsessions. In 2019, for instance, Monopoly released a digital voice-banking edition that doesn’t use cash, a House Divided edition where players buy states instead of property, and a Miss Monopoly edition in which female players make more money than men (they, for instance, receive $240 for passing GO) and players invest not in property but in inventions made by women. In 2020, there will be a belated Friends edition and a wildly garish limited-edition 500-sets-only version from Swarovski that features a tempered glass board, gold and silver foil printing, and more than 2,000 crystals. (I saw it at Toy Fair. It’s as absurd as it sounds.)

Just to reiterate, this is a game that not only isn’t fun, but was expressly designed not to be. It’s success and proliferation is perhaps the best example of capital winning over labor (represented, in this case, by better games like Settlers of Catan)

The fact of the matter is, there has never been a wider array of interesting, worthwhile board games to play. Let me name five: Settlers of Catan, Ticket to Ride, 7 Wonders, Pandemic, and Istanbul) These games that require luck, sure, but also skill and strategy. To play Monopoly is to lose — hours, friends, any sense of purpose — while reckoning with the very issues that have been tearing this country apart for over 100 years. So, to commemorate the 85th anniversary of our most ubiquitous board game, let me suggest an alternative: Don’t.