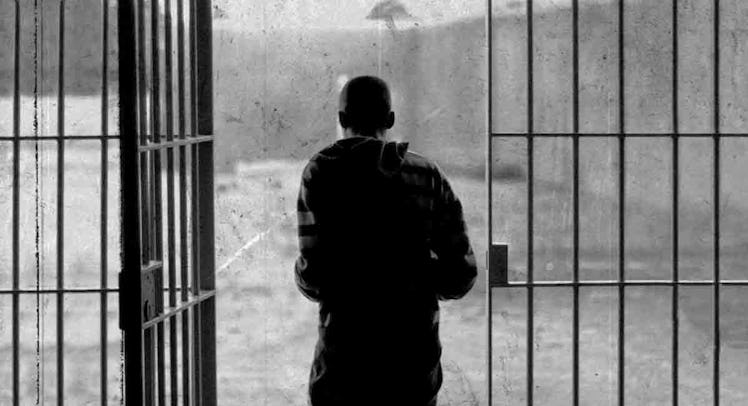

I Was In And Out of Prison For 27 Years. Now, I Help Incarcerated Dads Gain Their Footing

The first time I went to prison, I was 16 years old. Thirty years later, I'm a father of five and helping men who were just like me.

Rosalio Chavoya, a married father of five, is a Mentor Father at the Dependency Advocacy Center in San Jose, California. The DAC, a law-firm in which attorneys represent parents who are either incarcerated or rehabilitating to reunify with their children who have been put in the foster system, runs a sibling program, the Mentor Parent program. That program pairs their clients with counselors who can help them handle all of the hard work, classes, court dates, and parole meetings necessary to win reunification. Every single Mentor Parent has had their children removed from their home. Every single Mentor Parent has been through the reunification process and every single Mentor Parent was represented by an attorney at the firm. Rosalio Chavoya is no exception.

Rosalio was, in his own words, in and out of jail for the better part of nearly thirty years, starting at age 16, when he was tried and sentenced as an adult. His last stint in 2007 began a series of events he calls a “blessing, in hindsight.” His wife got caught by child services under the influence of drugs. His children were removed from his home. And for both of them, it was the catalyst that set them off to reunify with their kids for good. For Rosalio, it also turned into a career, one that he never would have imagined for himself.

Here, Chavoya tells his own story of incarceration, and what he loves about his work.

I had a history of being in and out of institutions. In 2007, I turned myself in for a two-year sentence. While I was in prison, my wife was with our kids. We had four children then. I found out, while I was incarcerated, that she was pregnant with our fifth. She was also still using.

Fortunately — well, depending on how you look at it, because I think it was a blessing in disguise in hindsight — there was a call to Social Services when I was incarcerated. They were doing a welfare check, where they check on you and your kids. They came and knocked on the door and nobody answered. My son peeked out the window, the property manager opened my door, and there was my wife, under the influence.

They ended up arresting her for being under the influence. Child social services decided to remove our children from the home. My father-in-law had an arrest from 30 years prior that he had to clear up before he was able to care for the children. So, my kids got split up between a satellite home and a shelter.

I had no idea that this was going on. About four days after it happened, I received a letter in the mail. That’s where they told me that my children had been taken from their mother. Being in prison, it’s not like you can go out and make a phone call. There was no way that I could even process this with anyone on the outside. I had my celly — my cellmate. He empathized with me, and we were able to talk it out. But it was just two weeks into my sentence. I felt powerless.

I got transferred to San Quentin. There, I was able to call my wife. She apologized. I stopped her midway and I said, “It’s not your fault. It’s my fault. I’m not out there. I’m locked up. I should have been there.” She promised me that she would do whatever she had to do to get the kids back.

ALSO: How John McDaniel Built a Family and Rebuilt Himself in Prison

At San Quentin, there was a pilot program that the warden started. About 200 service providers came into the institution. They led a class called “New Fathers.” I took the class. I was meditating, gardening. I was creating a peace of mind, and I was learning how to be a better person and father. It’s lucky that I was doing that, because when I went to court for the six-month review, I was able to say that this is what’s going on, and this is what I’m doing.

The very first time I went to court, coming from an incarcerated father, the very first time you go to court, your attorney interviews you, and the first question is: “Do you want a paternity test?” The questions keep coming: “Were you the only one that she was with? Were you at the child’s birth? Did you sign the birth certificate? Do you want the paternity test? Did you hold the child as your own? And bring the child in your home?” I understand that formality. But that’s the beginning of being doubted.

When I was doing all of the classes at San Quentin, my wife hit the books. She did what she had to do. And our kids got into her parent’s care. And I was doing everything I had to do while in custody. She reunified after 8 or 9 months. We already had section 8 housing, so we had housing established already. Then we hit the twelve month review. The timeline never stops when it comes to reunification.

MORE: Black Fathers Are Never Home And Other Lies Society Believes About Us

At the 12-month review, my wife was already done with all of her case management, her social worker was happy with her progress. They told her that they wanted to close the case, but she advocated for me, so I could regain custody. She had all my certificates that day with her and the judge was able to see it. She advocated to keep the case open for another six months. Otherwise, it would have been case closed, full legal custody rights to her. I wouldn’t have even had visitation. Because of that advocacy, they kept the case open. A month later, I was released. I still wasn’t able to see my family. I had to work on my own case.

I had to do a battery intervention course. I had to do a therapy without violence class. I had random drug testing. I was on parole. I had to do a family night, another parenting class. And I had to do all of those things while using the bus. A lot of formerly incarcerated people, that’s how we have to get around if we don’t have our license. Or anything like that. These classes, too, are in one city, and you live about two cities down, so you have to leave an hour or an hour and a half in advance if you’re on the bus. That is just what we have to deal with.

Today, I work as a mentor father for formerly incarcerated parents. Back then, there were no mentor fathers. I had a mentor mom, who was also the mentor for my wife. It was called the “Mentor Mom” program until they realized they needed to help fathers as well.

RELATED: America’s Incarcerated Parent Problem Is Now At ‘Sesame Street’

After eighteen months, our case was closed. That same day that they closed our case, I was approached by the Mentor Parent program to be in the position I’m in today – to help other fathers in this sort of situation, help them navigate their case plan and be there for peer support. When they asked me if I wanted the job, I looked at them cross-eyed: “I was incarcerated for all of these years. Have you seen my background?” But I went with the flow.

I now work with the Dependency Advocacy Center. They represent the parents who are fighting for custody. Within this attorney’s firm, there’s the Mentor Parent program to help communication between parents and attorneys. They hire people like us, with a little bit of experience.

There are currently eight mentor parents: three mentor fathers, and five mentor moms. We were all represented by these attorneys, and we’ve all participated in the mentor program and been through this process. If you have an attorney, it’s just not the same for them to tell people all that they need to do. It’s better to have us there, to give parents advice and navigation. To talk about what happened in our own experience. Everyone has their own story, but we know what they are going through, because we all went through it.

ALSO: When My Child, the Addict, Came Back to Me

It’s a traumatizing ordeal, you know? I got busted at 16 years old and was tried as an adult. I got out when I was 20. I have three different CDC-R (California Inmate Record Locator) Numbers. I’m 45 now. For 27 years, I was in and out of prisons, growing up in that kind of lifestyle. And today, to be able to trump that with helping others — I can’t believe it still.

I can’t believe that I’m able to help people out today, helping them sort through this chaos. Because that’s what I was used to for a long time. A lot of chaos, gangs, and drugs. For now, to be on the helping hand without having to go on any kind of special college, and things like that, solely on my life experience. We’re serving those people that I used to get high with. Those people that I used to go to school with. Even family members. For them to see me, someone that they used to get high with and do dirt with, helping them out — that’s one of those, if he can do it, I can do it.

People always tell me, “I can’t believe that’s what you’re doing.” And I can’t either! But here I am. It’s just one of those self-rewarding types of things. It keeps me going within myself, it allows me to feel good. People don’t understand that we change. We’re able to change. We can’t change history and what happened. But with the right resources, the right advocacy and mentorship, we can be guided in the right direction. We’re not always what you read on paper.

— As Told To Lizzy Francis