Parents Never Really Know Their Teenagers

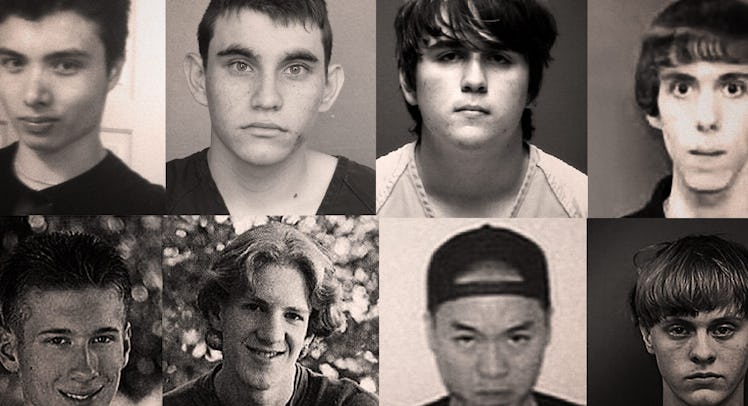

The Texas school shooting leaves parents of the shooter shocked, making it clear that we may not truly know our teenagers or what they’re capable of.

The parents of the Sante Fe High School shooter released a statement after the massacre expressing shock and saying that their son’s decision to murder his classmates with his father’s guns was “incompatible with the boy we love.” There is no reason to question this or the idea that the people closest to Dimitrios Pagourtzis, the people responsible for his guidance and care, were blindsided by his anger, cruelty, and world-consuming selfishness. Focusing on that fact is not simply a means of further shaming two gutted parents, but a violent way to illustrate a point: Our adolescent children are often unknowable and hoping for the best won’t get it done.

Adolescence is a time when kids have to learn how to become fully themselves. To do this, they often compartmentalize the part of their lives where they are experimenting with the dangerous acts of adulthood. They show parents what they want to show parents, and behind that skrim, they strike out into the turmoil on their own. And, yes, they are changed by their exposure to love, sex, violence, and other peoples’ kids. They transform in unpredictable and unidentifiable ways.

For the most part, adolescents lack the coping mechanisms to gracefully handle the rejection, conflict, and peer pressure they inevitably encounter. This leads to shame and silence. Parents may be there to help, but that doesn’t mean that help will be solicited. It’s naive to think otherwise. After all, teenagers are becoming autonomous people. It’s a critical developmental moment. Though they are responsible for their behavior, they are not responsible for this unfortunate circumstance or for the difficulties and pressures that come with high school.

So what is a parent to do if their kid isn’t letting them in? Do they shrug away the frustration? Do they just give them space and hope for the best? Or do they push and pry and risk further isolating their kid? Really, the only good answer appears a clear-eyed watchfulness, one unencumbered by the bias we naturally develop for our children. Because when they reach their teens, they are less ours and more their own.

“But not my child,” some will say. “I’ve raised my child right.” And it’s true, you may have done everything right. You may have had family dinners since your kid was in preschool. You might have had regular family meetings and open dialogue or strict discipline to fill their little heads with the proper values. But without an unwavering watchfulness in a kid’s teen years, those parenting tactics only serve to sharpen the dismayed statements after a tragedy: “We are as shocked as anyone else.”

If we’re honest with ourselves as parents, and we look at our own childhoods, the reality of what our children hide becomes visible. Luckily, the vast majority of us got through our teen years sporting the standard scars of adolescence: our first heartbreak, our first confrontation with drugs or alcohol, our first sexual experience or our first feelings of otherness. But how many of those scars were our parents privy to? Often, they are revealed decades after the fact, much to our mother’s and father’s chagrin.

For an unlucky few parents, the locked away lives of their children are revealed violently, in a hail of gunfire, or quietly when those lives are lost to suicide or drug overdose. If you’re a parent and the idea of your child harboring murderous thoughts scares the shit out you, good. You should probably have a talk with your kid. Maybe check in and see how things are going. Will they pour their guts out to you and ask that you take them to therapy? Probably not. But it will show them that you are ready and willing to talk.

At the very least, parents hearing the news from the shooting in Texas should take another look at the children they think they know. With so much of our teenage children’s lives occurring beyond our reach, it’s our duty to second guess ourselves. We should not make assumptions. Sometimes suspicion is a sign of love.