Along the Mexican Border, American Kids Face Racism and Bullying

Children are smart. They're more aware than they used to be.

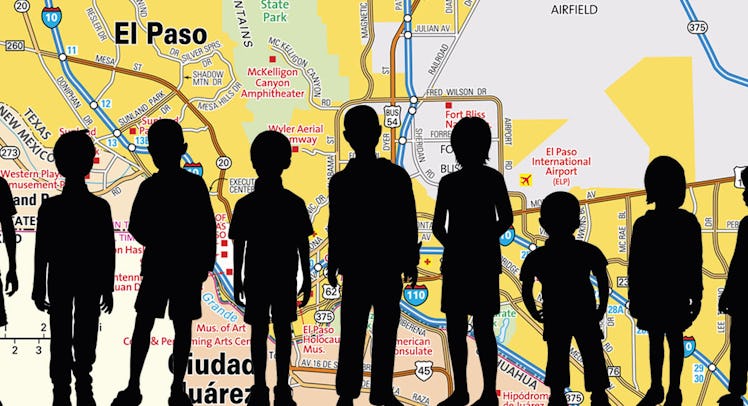

Viewed from above, El Paso is nearly indistinguishable from Juarez. In a way, they are twin cities and in a way they are one city with a bridge, a wall, and a number of Border Patrol agents standing in the center of town. Many Americans who settle in El Paso do so because they are of Mexican heritage — some82 percent of people in the city identify as Hispanic or Latino — and it feels like home. But that homey feeling is waning these days as stricter border control policies and new immigration laws breed suspicion and widen a political chasm. Even th kids can feel it.

Lili Resendiz, a substitute teacher, American citizen, and mother of two who was born in Mexico, knows this all too well. She’s watched children — her own son in particular — picked on for their roots. She’s watched anxiety grow in grade schools. She’s seen how parents coach their kids to withhold information. , loves living in the United States, she’s seen firsthand what a heightened anxiety over immigration. Here, Lilli talks about life in El Paso, and why it’s hard to be a parent.

Because we’re from Mexico, when we moved to El Paso we were able to have more from our country: the food, the language, people in common. I work in a school, and I speak English and Spanish, and at first I was like, “You know what? I haven’t even finished my certification, I’m not sure if they’re gonna accept me.” Especially because my first language is not English. But they said, “No, we need someone who speaks Spanish because 80 percent of the parents here speak Spanish.” I was like, “Really?” They said, “Yeah, we don’t care if you speak English, we need someone who speaks Spanish.”

I’m a substitute teacher. I work in the office. When the teachers don’t go to work, or they have meetings or training, they pull me out of the office and I will be in the classroom. I’ve been teaching kids from pre-k to 5th grade. We get extra support from the government because we have children with parents that don’t have income and resources. The school is actually in a very good area, very close to the golf club. You have houses that are worth a million dollars, so you have the kids with very high income parents, and you have children that live in an apartment or on military bases.

Where I work, at my school, there is something that we call ‘circle time’ in the morning. It’s when you sit down in the floor, you welcome the children, you ask them questions like, “What you are going to do this weekend?” “How’re you going to celebrate Mother’s Day?”, “What’re you going to do for summer?” It’s like that. Everyone knows and understands their culture. For example, the Mexican kids will say: “Oh yes, I am going to be this weekend with my Abuela and she’s going to cook me quesadillas,” and then the other kids would say, “My grandparents are not from Mexico, they don’t know how to cook, but we love Mexican food.” It’s like, children are very innocent, but they understand, and they will make comments about what’s happening on the border.

We cannot hide the situation anymore. You can tell which children are struggling with fear. Some of the parents will tell their kids, “you cannot say where you live. You cannot tell them that we live in Juarez.” They’re smart and they understand. I think that now children are being taught by the parents how to protect themselves, what to say, what not to say. Some of the parents live in Juarez, and they come every day and bring their kids, who are American citizens. But obviously you cannot tell if they live here or if they don’t, because the system doesn’t give us everything. As long as they bring the papers needed to enroll children, we don’t ask questions. That is all we need.

Still, some children say, “I live in Juarez.” You cannot deny them education. It’s complicated here in El Paso.

Children are smart — more aware than they used to be. We pulled my son out of private school is because he was in a classroom with just five or six American kids. One of the girls kept asking him — this was when President Trump was running in the election — when he was going to go back to Mexico. My kids don’t even have brown skin. They’re very white and they don’t speak Spanish. This white girl, she was pushing and pushing and pushing. She was asking my son over and over again: “When are you going to Mexico? Are you sad? Are you afraid?”

I don’t blame the child. She was 4-years-old. Her mom knew I was from Mexico, she was telling her daughter stuff. We moved our kids, because the principal didn’t want to have any scandal and said to just let it go. There were no consequences. Was it because I’m Hispanic? Was it because it’s a private school? It makes you wonder. And it’s really hard, you know, because it hurts and makes you feel that you don’t fit in the country. We love United States.

And there’s a point when you have to tell kids to stand up for themselves. You can walk away. Keep walking away, keep walking away. But, people are going to be pushing you and pushing you and they’re going to see you as different. Either you tell your kids: use your words and put that girl in the right place. Or you just keep your mouth shut and try to have better thoughts. It’s hard as a parent.

— As Told To Lizzy Francis