What Does it Mean to Be a Millennial Parent?

A look at what defines the latest generation of parents.

In 2016, 80 percent of kids were born to millennial parents, and with 71 million millennials, that is, well, a lot of children. But what does it mean to be a millennial parent? It’s clearly not just one thing: 71 million Americans are hard to boil down into terms like tiger parent or a permissive parent, and it certainly wouldn’t begin to describe the diversity of experience millennial parents have. But they do have one thing in common: millennials were shaped by certain economic conditions, cultural events, and by the styles of their own parents — which they decide to take or leave with them as they become new parents themselves.

According to the National Retail Federation, millennials are parents to half of today’s children. In 2016 alone, four out of five babies were born to millennial parents. To the extent that many dozens of millions of people have a defining, uniting sense of what it means to be a parent today is, of course, flimsy — but there are legitimate similarities worth exploring.

“Teachers kept coming to me and saying, ‘These parents are different.’ If you’ve been in education or any field long enough, you’ll always hear that — but I started to realize this wasn’t an ordinary generational divide,” says Jim Pedersen, an editor for 25 years and the author of The Rise of the Millennial Parents: Parenting Yesterday and Today. “These parents were actually different.” What did Pedersen see? A lot of parents who were fastidiously obsessed with their own kids’ success and willing to clear any and all hurdles for them.

Millennials, despite their breadth of experience and diversity, have plenty in common, and most of it has to do with their financial status and the sense that it is precarious. The oldest millennials had fledgling careers when the stock and housing market crashed in 2008; most graduated right into the madness of a contracted economy. As a result, millennials are the first generation in American history who are expected to have less wealth than their parents; the average millennial has about $36,000 in personal debt, excluding home mortgages. They also have fewer pathways to traditional wealth gains than their parents, with skyrocketing housing prices — the average cost of a home being about $30,000 more than it was in 1980. The average American can’t afford a home in 70 percent of the country.

Indeed, the financial situation of millennials is precarious, and made all the more precarious as public investment in goods like great public schools, good libraries, and welfare benefits shrink and parents feel left to fend for themselves. Millennial parents are also crushed by prohibitive costs of early childhood education: in many states across the country, having just one kid in full-time day care can cost as much as tuition at a four-year public college.

This economic reality has implications that go far beyond becoming penny pinchers. A Pew Research Center study found that a majority of millennial parents say that, compared to 60 percent of Gen X and just over half of Boomer parents, they are too overprotective. They are also far more likely to say that they give too much praise than earlier generations of parents with some 40 percent admitting they compliment their kids too much. Meanwhile, other generations say they are too quick to criticize. Most millennial parents — 62 percent with infants or preschool aged kids — say it’s difficult to find affordable and high quality child care. That makes sense; a Young Invincibles Report found that 18 percent of the costs of raising kids today are taken up by childcare and education; in 1960 it was just two percent of the total cost of raising kids.

So what about the typical accusation that says millennial parents are far too intensive and steer their children’s lives for them? This is, to a certain extent, quite true. Millennial parents spend close to an hour more taking care of their kids in 2012 than they did in 1965; today, moms spend 15 hours a week parenting their kids while all earners except for the extremely wealthy earn significantly less — the top 20 percent of earners saw incomes increase nearly 100 percent between 1976 an 2014 and middle class workers have only seen their incomes grow 40 percent over the same 40 years. The middle class, it must be said, is not alright. So parents turn to time intensive, overbearing parenting in hopes that it will secure their child’s future.

The aforementioned Pew study found that 61 percent of millennial parents say there’s no such thing as being “too involved” in their kids’ education. Jim Pedersen has seen this play out first hand. As a principal, he used to require parental permission for kids to withdraw from classes, and recounts the story he calls the “a-ha” moment for his book.

“One parent came in, and said what I was doing was a disservice to her son. She went off and said ‘And you wouldn’t take me out of my honor’s french and now you’re doing it to him.’” Pedersen told the parent that he wasn’t her principal, and she said, “Yeah, but you were just like him.” These types of moments — parents working through their own unresolved issues of their own childhood, the things that make them angry or hindered their success through the proxy of their children — was something he began to see a lot working in the school system. “It comes from a place of love. But sometimes it has damaging results.”

Millennial parents are, broadly speaking, relatively confident in their ability to parent, with over half of millennial moms saying they are doing a good job at parenting. Millennial parents are also way more likely to talk with their kids about money — almost half of millennial parents in a 2018 study by Capital Group said they’d start talking about saving money with their kids before they turned age 12. Money seems to shape a lot of their worldview, as moms who are millennials have kids later and later — likely due to the fact that most people can’t afford to co-parent on one income, and the majority of young parents today are dual income couples. The average millennial today makes $2,000 real dollars less than what they would have made in 1980, when their parents were parenting them.

Jim Pedersen describes the millennial parents psyche as similar to that of an informed consumer. “That is just how millennial parents are,” says. “They aren’t afraid to ask for certain accommodations for their children. It’s almost demanded. They’re more aware of policies and procedures than some staff and faculty in schools. They make noise.”

This is both good and bad. Parents should and can be advocates for their children in the classroom and in life, especially if they feel those institutions are not protecting their kids. As parents turn to more time intensive parenting and feel social supports erode, they have no choice but to be that person in their kids corner, because it feels like no one else is. But this intensive parenting can lead to a dangerous mix of overspending and overbearing.

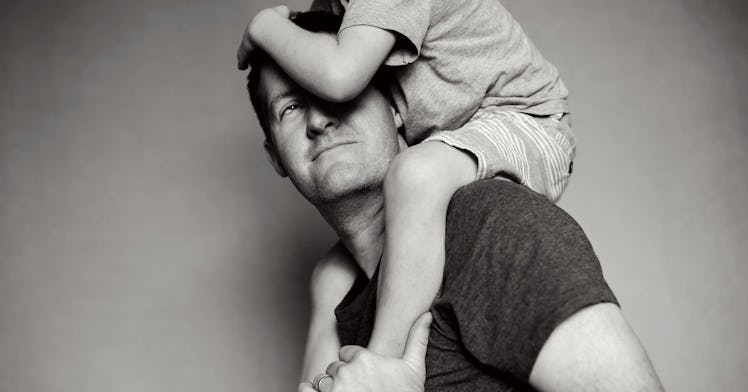

It really isn’t all bad news, however. Millennial dads are more involved with their children’s upbringing than any other generation of men before them. Millennial moms are way more likely to breastfeed than previous generations. Millennial parents have kids later in life than previous generations — the majority of millennials who are parents are in their 30’s and most don’t have their first child until 26. One quarter of women don’t have their first kid until they are 35. Research suggests that kids of older parents have higher IQs and a longer lifespan; older parents are more established in their careers and are, generally, financially better off.

But in terms of shared values — in what it means to be a good parent or to raise a good, healthy kid — millennials’ experience and opinions are too diverse to quantify. What does it mean to be a millennial parent? You might be a disciplinarian. You might enjoy free-range parenting. You might be the sports dad. But you are most likely over-scheduled, overwhelmed, part of a dual income family who struggles with debt, mortgage payments, and prohibitive child care costs. It means parents who want to prepare their kid for an uncertain financial future at any cost, who want to put them in extracurriculars, who want to put them on a track towards success. It sometimes means parents who are overbearing or who work to clear any and every obstacle. But hasn’t that been the tale of time? Millennial parents, like any other generation before them, just want the best for their kids.