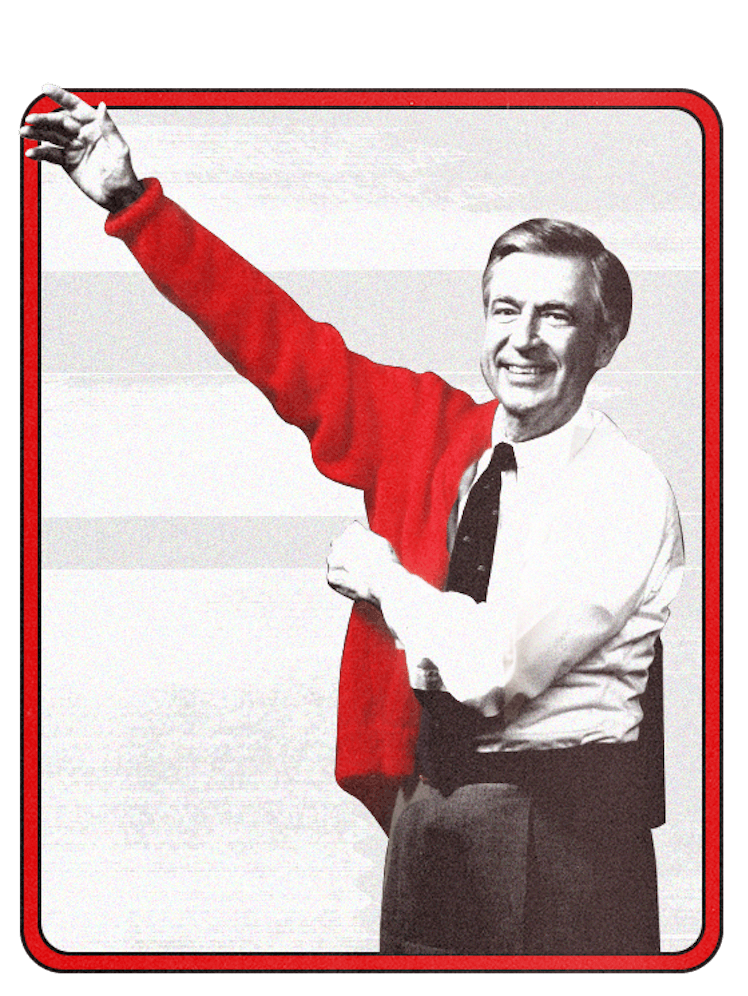

Why Fred Rogers Matters Now More Than Ever

Rogers has become the poster boy for goodness, but his greatness lay in the way he forced us to deeply consider ourselves and our feelings.

Fred Rogers’ relevance was born of his irrelevance. Nothing Fred Rogers ever did or said captured the zeitgeist or hijacked the national conversation. Rogers’ relationship with attention, which he borrowed and returned, was different than other performers and pundits. This is not to say that Fred Rogers was humble or retiring. He was an ordained Presbyterian minister who used television to construct a massive pulpit, but he didn’t want to hoard or hold children’s focus. He wanted to hold it up and show it to them one gleaming facet at a time. He wanted them — us, now that we’re grown — to see its value.

It’s cheap to say that the value of attention is at an all-time low. What’s closer to the truth is that our attention has never been more profoundly misvalued. The algorithmic FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) corrals eyeballs for profit and partisans stir sentiment for power, but neither the Silicon Valley timesucks or the demi-demagogues operate with the understanding that our attention is worth more to us than it is worth to them.

Fred Rogers understood this and it’s why he made a simple, hokey, and at times boring children’s show. Make no mistake, there was nothing unintentional about Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. The joke was not on Fred Rogers. The joke was on us. And it wasn’t ultimately a joke. It was a kindness. Mister Rogers, our pal with the crooked front tooth and the sloping shoulders, worked hard to be compelling enough that we would listen, but not so compelling we wouldn’t be able to hear ourselves. He did not game us, smash into the next episode, try to get us a click deeper (ask whether this browser tab was built for you), or optimize for entertainment value. The experience of watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was, at times, very similar to the experience of sitting alone in the room. That was the experience we needed.

Here are the questions that Fred Rogers asked children: What is your name? How are you today? What do you do with the mad that you feel? How many times have you noticed that it’s the little quiet moments in the midst of life that seem to give the rest extra-special meaning?

These are not scalable questions. There is no hockey stick growth to these kinds of insights. There is no enterprise value in the answers, which are worthless to everyone except us and those that love us just the way we are, including Fred Rogers.

We are special because we are alone and unknowable except to ourselves.

But we should be suspicious of the half-life of Fred Rogers — that documentary, the upcoming Tom Hanks, even Fatherly’s own Finding Fred podcast — posit him as a unifying figure because that’s how mass marketing works. Perhaps we did share the experience of watching Mister Rogers talk to fish, play with puppets, and chat with children on the streets of Pittsburgh, but TV is ultimately atomizing. Mostly, we watched alone. Rogers knew this. He was always suspicious of his medium. He stretched its limits (I love to play with blocks, don’t you?), but resigned himself to his box. His show — the one he produced, curated, and perfected in the box — is therefore trustworthy in a way that our memories of him are not. Tom Hanks might do a good Mister Rogers, but it’s a bit in service of mass appeal and mass consumption. Fred Rogers was uninterested in that kind of spectacle, however sentimental. He was reliably more interested in individuals — and celebrating them — than in groups.

Why? Because coming to grips with one’s self is the core experience of childhood. Because our answers to Mister Rogers’ questions are different. In Freddish, Rogers’ language of care, “special” is not a prescription for pampering but an inarguable truth. We are special precisely because we are different. We are special because we are alone and unknowable except to ourselves. You’re special to me, he would sing. You are the only one like you. If you can quiet yourself enough to really hear that line, it’s alienating. Also empowering. Also true.

That said, though we are all one-offs, we share many things — principally weaknesses. If the last decade has taught us anything it is that those weaknesses render us collectively hackable. We can be riven and overridden by targeted ideas and targeted advertising. We can be convinced to andchill instead of visiting our friends (inside the Land of Make-Believe or not). We can be undone by our equations. Our attention can be taken from us.

When we think of Fred Rogers, we’re reminded us that it can also be taken back. With force if necessary. With kindness if practicable. But totally and absolutely until we’re just sitting by ourselves again, thinking about our feelings and marveling at our own dimensions.

I can change all my names

And find a place to hide.I can do almost anything, butI’m still myself inside.