I Parented Like A Chinese Dad For A Week And My Kids Do Chores Now

An American dad in Ohio looks abroad for inspiration — and finds some insight.

In 2011, author, lawyer, and Chinese American Amy Chua hit the bestseller list with a manifesto for overbearing parents titled Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, in which she made the case for stringent, results-focused Chinese parenting. Chua walked right up to the line of calling American parents sentimental wimps (even putting a toe over it in some interviews) and a lot of people took it personally. Chua was pilloried with racist terms across the internet. But her book sold because the idea of “just do it better” resonated naturally on some level. Chua was telling parents to say a thing they’d kept bottled up. She was telling them not to be warm and fuzzy.

For me, this notion was antithetical to every instinct. In my house, we talk about feelings. But, starting a few weeks ago, I was rethinking my resistance. My oldest was struggling with disciplinary issues in first grade, and I felt like I was lacking the tools to come down hard. I decided to overcompensate. Chua would be my guide.

“Even when Western parents think they’re being strict, they usually don’t come close to being Chinese mothers,” she wrote. “For example, my Western friends who consider themselves strict make their children practice their instruments 30 minutes every day. An hour at most. For a Chinese mother, the first hour is the easy part. It’s hours two and three that get tough.”

Every parent is different no matter what culture they hail from, but research shows that Chinese parents often share traits uncommon in Western households. They also — and it’s important to note this — often share traits that were common in Western households a few decades ago. For instance, women are often expected to run the household while men work. This happens to be the arrangement in my house. But kids doing chores and suppressing their emotions are not part of the arrangement. I was, naturally, curious to see what would happen if I very suddenly changed that.

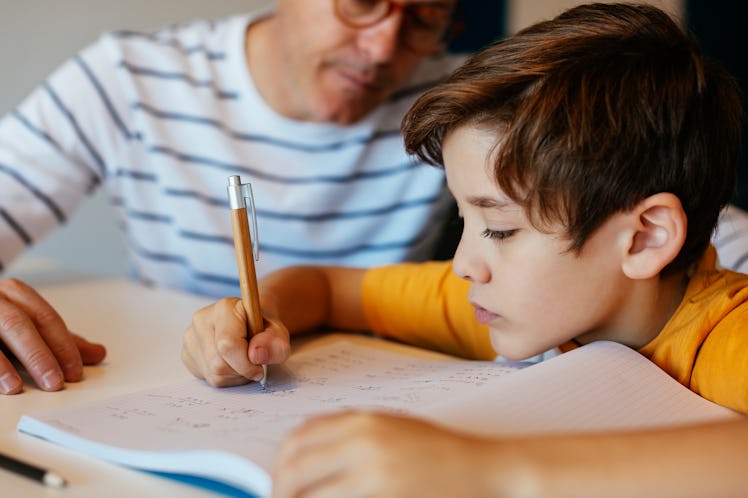

My son’s school had just sent home a newsletter explaining that it was time for end-of-the-year testing. First graders would be expected to count (and write) from 1 to 60 and would be expected to be able to spell a slate of vocabulary words. Considering our kid was already on his teacher’s bad side for rarely lifting his head off the desk, I decided this presented a perfect opportunity to instill a strong work ethic.

He was not pleased. But like good Chinese parents (or like two white people in Ohio pretending to be good Chinese parents), we tried not to think too much about how he felt on the matter. That led to some epic meltdowns on all sides. His whining and attempted diversions were deeply infuriating.

“Just write the numbers! You would have been done an hour ago if you would just concentrate!” we explained very loudly.

It was clear we were missing something, and a bit more research revealed the problem was a flaw in our messaging. We had to learn to emphasize practice more than anything else. So we encouraged him to practice, practice, practice, even pushing him to write to 100 rather than the expected 60. The counting and spelling was a nightly task, beyond his daily homework. It sucked for everyone.

Meanwhile, we were also tightening the screws on the high emotions that tend to run in the house. The new rule? Your apparent anger and sadness will not be tolerated. If you need something, you come to us calmly.

By Thursday, the kids were taking deep breaths before airing grievances. That was nice, but the number and spelling work continued to be a strain. It just took so much time. It also made parenting feel like real work. It ate into our personal time.

Those two things, parenting and personal, could no longer be conflated. My wife was ready to break.

Then we had a breakthrough. On Sunday, we split the family up into two teams for a deep house clean. We told our children that they had tasks and it was imperative they do them. Interestingly, the boys took to the chores easily. The little one vacuumed with a hand vac. The big one jumped into dusting with a deep pride and concentration.

“I want to start a cleaning service in the summer,” my 6-year-old said. I had a sense he could pull it off. In the end, there was less for my wife and me to do. I wouldn’t say we regained the hours sunk into numbers and vocabulary, but our time debt had been slightly reduced.

We saw that had this been our normal way of doing things, the boys would likely be so used to household duties it would be easy to acculturate them into academia. It would also be easier to keep the house clean. We decided this was very good for us and that it might be the new normal.

Still, we failed at some other tests. Research suggests that Chinese parents are stingy with affection, preferring to show love through acts of sacrifice. That’s beautiful in a stoic kind of way, but my wife and I are not stoic at all. We are completely incapable of holding back our vociferous adoration of our kids — even for the good of our kids. It could be easily argued that we’re selfish in that regard, and maybe that’s right. Either way, it’s not something that’s ever going to happen.

That’s why we went crazy with hugs and whooping when our kid came home with a practice test number sheet that was nearly perfect. We hugged him and praised him and smiled and gave high-fives. We were happy for him and about his new work habits, but we were also happy for ourselves. Our work had paid off. This felt good.

My son beamed while he pointed to his well-formed numbers, bringing my attention to the last few numbers where he’d counted to 500 by hundreds: 100, 200, 300, 400, 500.

“Look! I went all the way to ten thousand!” he exclaimed wrongly.

My wife looked at each other. We were happy, but also a bit sad. We had to correct him. The tiger parenting had been so effective that we couldn’t in good conscience stop. At the same time, it sucked a bit for us. It was, in short, time for a stoic act of sacrifice. So that’s the thing my wife and I are practicing now.

This article was originally published on