How a Decorated Marine Disciplines His Kids

Jason Schauble is a former Marine who fought in Fallujah. Now a father of four sons, he explains how he uses military techniques to help them grow into young men.

Jason Schauble is a former Marine who led troops in Iraq and fought in the Second Battle of Fallujah where he earned a Silver Star, a Bronze Star with combat distinguishing device, and a Purple Heart. After being wounded in battle, he helped stand up both the Foreign Military Training Unit and the Marine Special Operations Command. Today, he lives in Austin Texas with his wife and four young boys, aged 10, 8, 7, and 7. In his role as a father, Schauble’s utilized much of his significant training and experience to help his four sons grow into caring, self-disciplined young men who understand that they are part of a team. As one might expect from such a decorated hero, much of this includes never taking the easy way out.

The highly decorated veteran spoke to Fatherly about the lessons he passes down to his kids, the use of honesty in his parenting, and why planks are a better disciplinary tactic than time outs.

I find that one cause of a lot of problems between parents and children is either being told, “You’re not old enough for that,” or someone just outright lying to them, with few exceptions. So I try to be honest with my kids about everything, even when the topics are very difficult. When they asked me what happens after you die, I gave them a spectrum of outcomes. “Some people believe this, some people believe that, and when you’re old enough, you can figure it out for yourself what you think is the right answer.” That’s a lot harder of an answer to give than “You’re not old enough,” or some assured answer like, “Of course, everyone believes this,” when that’s not really true.

Read more of Fatherly’s stories on discipline, behavior, and parenting.

For example, one of my kids asked a girl at school about her private parts, because he didn’t understand there was a difference between the two of them. He’s in the second grade.So the school told me he had done something wrong. He didn’t do anything wrong, he’s just curious and no one’s ever told him. And that’s because our society believes that we can’t talk about this.

So I sat all my kids down, and was like, okay, I guess we’re doing this now. I got the coloring book of the body systems, the nervous system, the central system. I had two kids that were asking all sorts of questions and two kids who were absolutely mortified and blushing and wanted to get the hell out of there as fast as possible. I haven’t had a lot of questions since on that topic. But I was like, hey, this is an example of something where an easy way out is to say, “Go ask your mother,” or “We’ll talk to you about it when you’re 15.” But I’d rather they at least know some version of the truth that is fact-based than going to ask their friend, who is equally uninformed, and then walk around thinking something that is completely wrong for a long time.

We have to be very organized with four kids going to school. Every kid has a color. I have a kid who is green. I have a kid who is blue. I have a kid who is orange and a kid who is red. Their backpacks, their water bottles, their lunchboxes, everything that could be traced back to them has a color on it. That way I immediately know whose shoes were left out, whose water bottle was left out. Everything has a place and it goes back in that place.

Their rooms are all organized in the same way. A lot of this is military equivalent of Standard Operating Procedure. If they’re staying in another room, they know where all the stuff is kept.

I also teach them survival. I teach them about firearms because I think it’s important that they know over time. My kids all shoot bows. I’m in Texas — in some parts of the country, they’re like “Don’t ever let a kid touch a gun.” I’m on the other side of it. Teach a kid gun safety, teach them how guns work, don’t make guns a taboo thing, and your kid will respect it but it won’t be like, “Oh, this is the thing I’m not allowed to touch. I need to touch it.”

I teach them, “This is how a gas mask works. This is how a first aid kit works. Here’s how you put a pressure dressing on. Here’s how you take apart an AK-47.” We do those every weekend. I’d rather they be at least somewhat capable, that they have some idea of how to make a fire.

We do a lot of active time with them. We give them responsibilities and chores. We set up systems that make our lives more efficient, that they understand are repeatable. Those are all military style things that I borrow from my time in the Marine Corps and the Special Operations community.

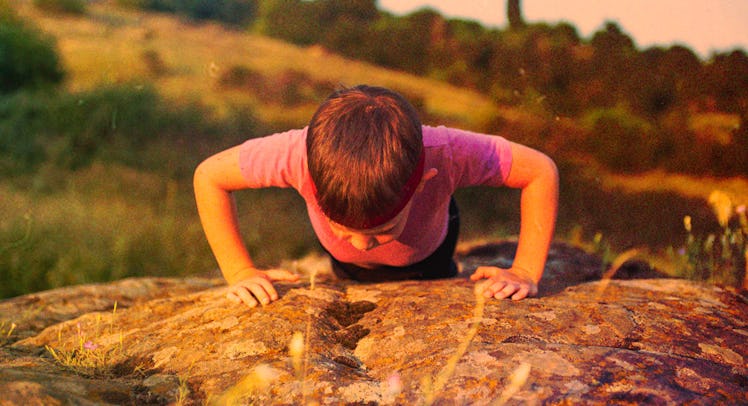

My kids do push-ups, planks, or wall-sits, all of which are lovely contests I learned in the Marine Corps for group punishment. Like when they all get in the car, and they leave the door open and the dog runs out around the neighborhood? I’ll have them plank until I go get the dog and bring him back. They know that’s a consequence.

As much as I would love to get to the bottom of every dispute, sometimes it’s best to say, “Everybody give me 10 push-ups,” and we can move on. And with little boys, that’s very effective. I’ll make them do it in a grocery store, at a restaurant, at a family gathering — it doesn’t matter. At least they know, “I do this, it’s over, I move on.” I don’t carry it with me, and they don’t carry it with them.

Every kid is different, but some people like to discipline by saying, “Go sit there and do nothing. Have a time out.” I’m not a big fan of that. Time is important. If you put a kid in his room, that’s not really a punishment. They’re like, “Great, I get to go build Legos or read a book.” Punishment, in my opinion, needs to be immediate and related to what happened, so they associate, “Hey, this is what I did wrong, I paid for it, and I’m moving on.” This is the price of being a part of a team.

My kids are sneaky. You can’t avoid that. You put systems in place and their immediate job is to try to work their way around those systems. I fundamentally believe that children are inherently selfish and it takes years and years of teaching them basic things like thankfulness and gratitude and to care about others. I try to inculcate that early and say, “Look. You’re a part of a team. What you do affects the team. If you’re late, if you’re slow, if you don’t pack your toothbrush and you have to use someone else’s on this trip, that sucks for that other person.” These are the reasons why we do the things we do. So when they make mistakes, we view those as teaching moments, but by no means do I run a household with an iron fist. I try to find the right balance between “Hey, there are rules,” and “These rules are here for a reason.”

Kids need to know you’re watching until self-discipline is established. Their mom and I are both very self-disciplined, driven people, who do our own thing and don’t require a lot of guidance. So it’s hard for us, because we’re like, “Why do you constantly need somebody on you to do this?” But you don’t start out that way. They’re going to make mistakes, I just tell them, don’t be the guy who is always that guy. Don’t make the same mistakes over and over.

— As Told To Lizzy Francis

This article was originally published on