My ‘No Homework in Grade School’ Policy Backfired Spectacularly

Homework for grade-schoolers often seems overwhelming and ridiculous but it also forces time to bond that might not otherwise be there.

My wife and I stared at our first-grader as he broke down into sloppy tears. We were, at least for a second, too stunned to recruit — too confused really. I’d just told him that I wasn’t going to make him do homework for a week. He was right on the edge of inconsolable. He was terrified.

“But my teacher will get mad at me!” he said through hiccupping sobs. “She will have to give me zeros!”

“Are you afraid of your teacher? Or are you afraid you’re not going to learn the stuff you need to?” I asked softly.

“Both!” he wailed.

READ MORE: The Fatherly Guide to Homework

My wife and I exchanged concerned glances. This is not at all the reaction we’d expected. This is not at all the reaction we had hoped for or anticipated.

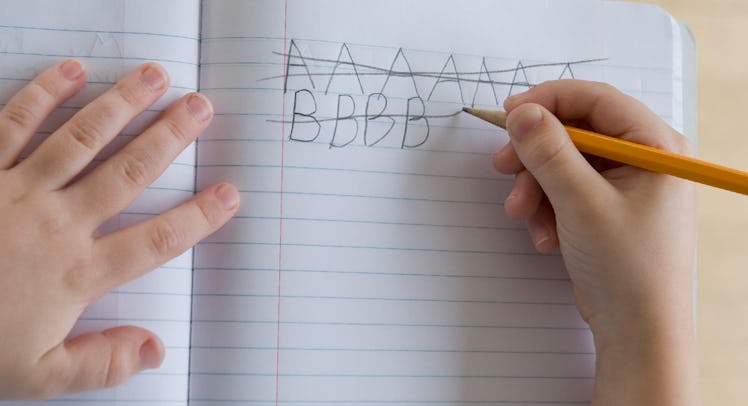

For the last two years, homework has been a struggle for my second grader. The daily worksheets he’s reluctantly pulled from his bag every afternoon since his first day of Kindergarten looks heavy in his hands. He hates homework. We hate making him do them. There’s a lot of recrimination involved, there has never seemed to be much learning.

My frustration with the homework situation intensified recently when I went on a search for proof that homework helps young learners. I found none. Instead, I found studies showing that it may erode interest in academics. Furthermore, I found a lot of researchers suggesting that spending time away from school playing outside or communing with family is far more beneficial for grade schoolers.

So, being a guy who cares about evidence and also a guy who doesn’t really want to make his kid do homework, I decided to see how a no homework policy would work out for my kid and for my family.

MORE: Why Schools Should Give Kids Homework From The Guy Who Wrote The Study On It

And that’s how I ended up trying to talk down a 7-year-old. I assured him that if I sent a note to his teacher, explaining what we were going to do, she would understand. He was skeptical but buoyed up by additional assurances that we’d be spending homework time either outside playing or just hanging out. I suggested we might even see if our playtime could incorporate his homework topic. Eventually, he started breathing regularly.

(Incidentally, I did send a note to his teacher explaining what was going on. She was happy to play along but asked that we sign his blank homework sheets to show that we’d seen them. I immediately forgot to sign them.)

That afternoon, instead of pulling our hair out over his homework, we sat at my computer and played a few rounds of Pokemon online. I made him read the digital cards and calculate hit points. I made him think up his strategy. I told myself this was educational. It was definitely fun.

But over the course of the next four days my intentions to spend my child’s homework time doing something vaguely educational and mostly fun wilted away. It’s not that I didn’t want to spend time with him. I totally did. The world conspired against us. One afternoon, I felt sick and lousy. I could barely rouse myself to dinner, much less play the measuring game I’d planned based on that week’s first grade math skill. The next day was swim class for him and his brother and by the time dinner was over, it was time for bed. The day after, it was snowing and too cold to play outside.

ALSO: 4 Homework Myths That Parents Should Consider

Being aware of our experiment, my son would plod up to my office every day after school and offer some fantastic idea, like painting or going for a walk. And every day I had to decline for some reason. Eventually, he’d go find his brother and paint or play.

And it’s not as if not doing homework changed his attitude about school in any significant way. He was still counting the days until Saturday. He was still dragging his feet to the end of the driveway to meet the bus.

I’d expected that without the pressure of homework a load would be taken off his shoulders. It was, in a way. But then that load was placed on mine. I’d told him and his teacher that I’d take the responsibility of providing some semblance of afternoon education and play. Aside from the Pokemon game, I pretty much failed.

And that’s when I began to wonder if homework wasn’t such a terrible idea after all. At least when homework was required my wife and I would be compelled to sit beside him, help him manage his emotions while learning, you know, something. Homework forced my hand. I didn’t think I needed that pressure. I didn’t think I needed to be pushed, but a week later, I was thinking that maybe I did.

RELATED: Why I Never Made My Kids Do Their Homework

When my son and I were left to our own devices, without the weight of educational bureaucracy on our backs, we allowed the world to pull us away from one another. Sure, we weren’t battling over writing simple sentences, but then again, we weren’t doing much of anything. I was too tired, busy or unmotivated to get creative and build some sort of wonderful educational moment.

That had been my dream, in a way. To show the public education system that between my smarts and my son’s natural curiosity, we could come up with something better. Instead, I inadvertently discovered why the public education system deems homework necessary — parents are tired and can’t be trusted.

Does that mean I regret letting my son spend afternoons playing with his younger brother? No. Do I think his education was harmed in any way by not doing homework? Probably not. But I do feel like, without homework, we lost facetime and interaction around his education that most likely provides important insight.

RELATED: Elementary School Homework Probably Isn’t Good for Kids

Spring break is coming. Luckily we’ll have a week to regroup. And when school starts up again, I’ll be at the table with him and his homework, a little less frustrated by the task knowing it’s bringing us together — that it’s for me as well. And maybe now that I’ve accepted it, he will as well. Maybe not.

This article was originally published on