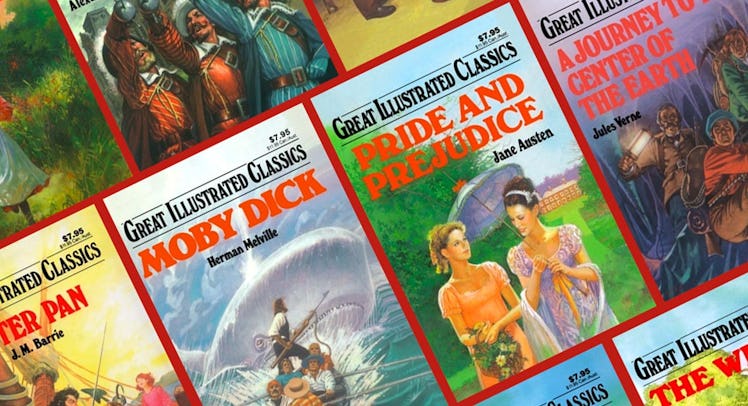

Are Great Illustrated Classics Great For Kids?

'The Time Machine' isn't very faithful, but the slimmed-down 'Moby Dick' might be useful.

There’s a bizarre song in Shirley Bogart’s Great Illustrated Classics version of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine that, somehow, is sung by a character who is supposed to be mute. Despite the fact that her version it is billed as an adaptation, Bogart made up the song out of whole cloth. It’s sung by Weena, a character who is pretty much silent in Wells’s book but speaks and sings throughout Bogart’s adaptation. And Wells came to Bogart in a vision and told her to add a creepy song to his most famous work, she’s engaging in an egregious act of artistic vandalism. Thankfully, most of the 65 other titles in the Great Illustrated Classics series don’t contain such dramatic alterations. Instead, they simplify the language and illustrate the action in order to make classic works easier for young readers to understand.

This brings us to a question that parents need answering: Even if they are relatively faithful to the originals, are these simplified, illustrated versions of classic works actually good for young readers?

There are two main schools of thought. Yes, because, as the publisher says, the books “encourage skill development in boys and girls at various reading levels.” In other words, they are tools for building literacy even if they don’t qualify as literature. The other viewpoint sees them as hollow simulacra of the original works that do a disservice to their young readers by removing what makes the classics classic in the first place. (This is likely the view of the enterprising prankster who listed “I. Dummitdown” as a co-author on many of the books in the series on Amazon.)

To understand the debate it’s worth examining a more typical Great Illustrated Classics treatment, Moby Dick, also adapted by Bogart. At the beginning of Melville’s novel, Ishmael is experiencing “a damp, drizzly November in my soul” and it seems as though he is “bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet.” He’s really bummed.

Melville’s language has a rhythm, commas, and semicolons both separating and connecting vivid descriptions. Reading it you don’t just know what’s happening in Ishmael’s heart, you feel it.

The parallel phrase from the Great Illustrated Classics edition is “whenever life got me down.” The writing is far less emotive, but for young readers, it is much easier to understand. Is this a good thing or is the loss of Melville’s language not worth it?

Both arguments have merit. The determining factor seems to be how much guidance young readers receive when they are introduced to the series.

Literacy expert Dr. Timothy Shanahan, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, thinks that books like those in the Great Illustrated Classics series do have the potential to be useful tools.

“I think it is great that kids get exposed to classical literature, even if it is not as fully realized as a more traditional version,” Shanahan said. “We want kids to know myths and how stories are told. There are particular tales and characters that we want them to know.”

Like the TV series Wishbone, the Great Illustrated Classics series introduces kids to stories they should know to be culturally competent. Kids who read Great Illustrated Classics will know which ghosts visit Ebenezer Scrooge, see where Phileas Fogg travels, and understand the humiliation of a hungry Oliver Twist. One important caveat: the series skews heavily towards Western, white, male authors.

The illustrations help too. A 2016 study from Hamline University found that language learners performed better on both short- and long-term memory-based assessments when they read a graphic novel version of a story as opposed to a text-only version. Another study by a Japanese researcher showed that reading a graphic version of a story leads to better understanding of a text-only version read afterwards.

Then there’s the fact that most kids can’t read the full version of these texts anyways according to Lexile scoring, which Shanahan calls a “well-validated scheme for placing texts on a continuum of difficulty.”

The unabridged version of Ivanhoe has a Lexile score of 1410L; the Great Illustrated Classics version has a Lexile score of 990L. For context, the company behind Lexile recommends sixth graders read books between 690L and 1160L. So, the average sixth grader would likely find the unabridged version too difficult to get through and the Great Illustrated Classics edition well within their abilities.

However, reading an easier retelling of a complex text doesn’t allow the reader to do the difficult but rewarding work of comprehension.

“The presentation form is less like the materials one reads in college or the workplace,” Shanahan said, “so the reading practice wouldn’t be as beneficial as reading a more traditional version.”

In another study cited by Shanahan, high school students who read the graphic versions of a work finished in less than half the time. That is simply a lot less time spent practicing reading, which isn’t great.

So what is a literary-minded parent to do? An outright ban on Great Illustrated Classics seems misguided. If your kid is an avid reader, chances are you won’t be able to keep them from picking one up, and they are useful for building knowledge of important works of culture. Your job as a parent is to make sure your kids know that longer, more rewarding versions of those stories exist and that they are worth experience even if your kid has already read the Great Illustrated Classic edition.

“It is wise to make sure the kids know there are more elaborated versions that they might want to read someday,” said Shanahan. “Not a bad idea to plant those seeds.”

This article was originally published on