Beatrix Potter’s ‘Peter Rabbit’ Was Always a Cynical, Violent ‘Mad Max’ for Kids

You may remember this as a wholesome book. But you would be very wrong to remember it that way.

The new live-action Peter Rabbit movie, which hit American theaters last week, has received mixed reviews from both critics and the sorts of parents who take to Twitter as the credits roll. And, yes, the film may be a ham-fisted attempt to update a beloved classic, but anyone who claims the movie somehow sullies the saccharine purity of Beatrix Potter’s book clearly hasn’t read it. Like many classic kid’s books, Peter Rabbit is dark, cruel, and full of ominous portent. Beatrix Potter had a charming name and could do wonders with watercolors, but she didn’t exactly have a rosy worldview. Peter’s dad, it is clear on page one, has been eaten in a pie. And it only gets more Mad Max-ian from there. If Peter is the main character of the story, it would be fair to say that death, perpetually peaking out from behind thorny bushes, gets second billing.

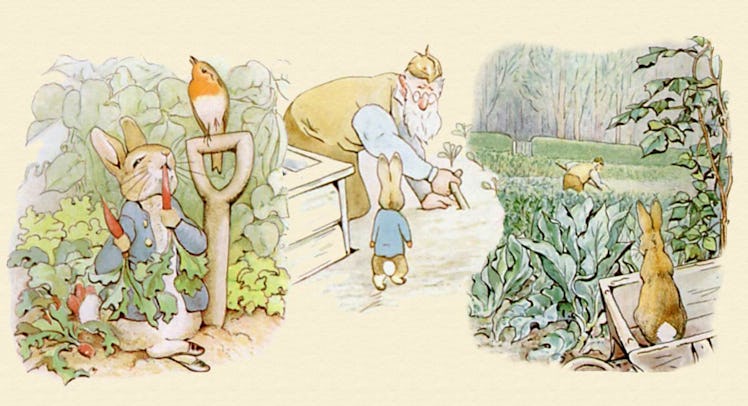

Peter Rabbit, the book, has a sort of zany nihilism that people seem to forget on account of the nice illustrations and the general cultural amnesia on plot points. The titular bunny doesn’t just have a fraught relationship with Mr. McGregor, the old cranky farmer. The antagonists are engaged in a battle of wits with life itself at stake. There’s a reason Peter’s mom warns him early on that he and his sisters better not steal food from McGregor’s garden. McGregor is a full-on sociopath who, in a Marxist reading, would be described as being engaged in the suppression of the disenfranchised. In a non-Marxist reading, he might best be described as a very bad dude.

The moral vectors of the story are interesting in that the Rabbit family does not ever really consider the problems with stealing. They take what they can and concern themselves only with mortal consequences. This is both understandable and important to keep in mind when considering Peter Rabbit as a character. Like Bugs Bunny, his charm is derivative of his ability to wriggle out of a bad situation not his intentions. He’s more Artful Dodger than he is Oliver, which means that he’s not a goody-two-shoes or a bore, but also that he’s not exactly admirable either.

He is, however, extremely determined.

Peter’s sisters wisely heed their mother’s advice and head off to safely pick blackberries elsewhere, but, like (or perhaps because of) his late father before him, Peter can’t resist trying to get some of the good eats growing in McGregor’s garden. At first, it seems like Peter might get away with it, but he’s gluttonous and winds up needing to find parsley to help cure his stomach ache. Predictably, he is spotted by McGregor. A furious chase quickly ensues.

Peter temporarily manages to escape being the main course of the McGregor’s dinner that evening but in his state of heightened desperation, he loses his clothing and ends up having no clue where the hell he is. Most would write that dangerously close-call off as a win and go home but not Peter. The arrogant rabbit makes the inarguably foolish decision to try and get his clothes back, perhaps hoping to save face and not admit to his mother that he blatantly defied her warning. Peter is, of course, easily spotted by McGregor and once again he is on the run.

It’s worth dwelling on the clothes thing for a second. McGregor is aware that rabbits wear clothes, which is a strong indication that we’re not in the Bambi-verse. The farmer is knowingly trying to kill intelligent animals with families. Again, this is more Hatfields versus McCoys than it is Sunday shooting. McGregor puts Peter’s lost clothes on his scarecrow as a statement and a warning sign. Peter goes home in the altogether and watches his more virtuous sisters eat a full meal.

What is the lesson here? Listen to your parents? Not really. The joy of the story is derived from Peter’s intransigent cockiness. Peter Rabbit is not about goodness. It’s about getting away with badness. Also, revenge. It is petty and cruel and extremely well written. It is not, however, sweet. The illustrations are. And you better believe that was intentional. Beatrix Potter is rightly credited with inventing character marketing and the Peter Rabbit empire is currently worth north of half a billion dollars — likely more post-movie.

Ascribing sweetness to unsweetened children’s books is nothing new. Remember Charlotte’s Web? Remember The Giving Tree? Peter Rabbit is a brutal book that has now been made into a less brutal movie. Whether or not the movie is itself an act of cynicism may be an open question, but the artifact is definitely more optimistic than Beatrix Potter’s book. Why? Well, there’s a clear answer there: Potter lived among rabbits and farmers and also in reality. She was telling a story about a real place, not about a nostalgic or warm feeling. The farm, to Potter, is not a metaphor. The rabbit, to Potter, is a rabbit. That’s what makes the book work and also, on some level, what must inevitably decouple it from a product of CGI.

Peter Rabbit has suffered the same fate as a lot of similar IP. It exists in actuality and in the popular imagination in totally different ways. Why did parents expect a tidier tale? Marketing, pure and simple — roughly a century of it. They got duped. It’s enough to make one sympathize, fleetingly, with the angry farmer.

This article was originally published on