Dr. Seuss Lied. The Cat in the Hat is Not a Cat.

No one is saying that Dr. Seuss's opus isn't an excellent book. But there's a lie right there on the cover and it's time to call it out.

According to legend, Theodor Geisel, Dr. Seuss himself, created The Cat in the Hat in response to boring grade-school books like Dick and Jane. Reaching for a list of easy-to-learn words, Geisel grabbed “cat” and “hat” and was off to the blue-haired, red-suited races. In more than one interview, Dr. Seuss noted that he intended for the Cat in the Hat to represent a kind of revolutionary spirit and scholars have posited that Cat in the Hat represents Geisel himself. These are all interesting points and the book warrants a close-reading, but insight into Dr. Seuss’s motives won’t address the most problematic thing about The Cat in the Hat, namely that the Cat in the Hat is not a cat.

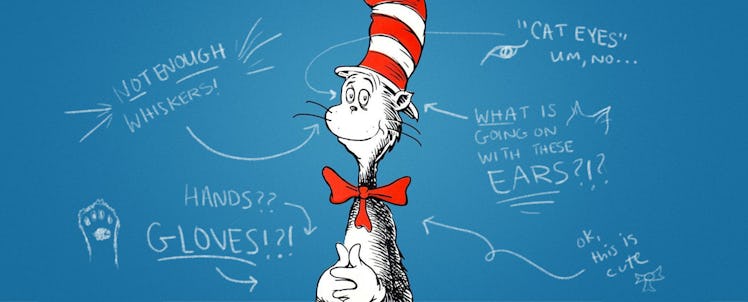

Anatomically, this should be obvious. The Whatever-It-Is in the Hat has small ears, round eyes, no snout to speak of, only a handful of whiskers, and long snaking tale. What seems clear is that Dr. Seuss chose the words cat and hat because he knew that toddlers could pronounce them and then just drew whatever he wanted to draw. I noticed this after my toddler quickly picked up on the narrative misdirection. She calls the book One and Two, referring to the Cat and the Hat’s partners in mayhem, Thing One and Thing Two. Personally, I think my daughter has stumbled onto a more appropriate title: Thing One and Thing Two Go Bump. It does not contain a lie. The un-Cat in the Hat, who’s feline nature is never revealed in the text or imagery, is not misidentified in this title.

Let’s dwell, just for a moment, on the C in the H’s behavior. He rides a vacuum cleaner and exhibits loyalty to two mutants. If he is a Cat, he’s a very strange sort of cat — perhaps a clone hybrid of some kind. Upright talking animal are a common literary trope (see: Jonathan Lethem’s Gun, With Occasional Music, Robert Repino’s Morte and Ringworld novelist Larry Niven’s Kzin, featuring an upright alien cat species at war with humans in space), but most writers have the courage to own it.

Cat-creatures in fantasy, sci-fi or cartoon narratives usually have some sort of feline habits, just so the reader/viewer knows this is still supposed to be a cat. Sylvester in Looney Toons licks his paws, and Tom from Tom and Jerry wants to eat mice. Even Catwoman — a human dressed as a cat — purrs. Eartha Kitt, a human, used to do a better impression of a cat than the Cat in the Hat has ever done.

Hanna and Barbera /MGM

The Cat in the Hat doesn’t even try to eat the fish. Instead, he dresses like a dandy and fucks up a suburban household (alright, that last bit is slightly cat-like). The broad conclusion that must be drawn from all these data points is simple: The Cat in the Hat is human. If you think about the physique, which is basically built on the common Seussian chassis, and the demeanor, it makes more sense that this character is a weirdo in a cat suit than that he is a very, very large cat. This is actually cooler anyway. It’s smart.

In Flannery O’Connor’s legendary novel Wise Blood, a depressed man in a gorilla costume is murdered by a man who tries on the gorilla costume himself, gambling about in the woods. Has something similar happened with the Cat in the Hat? Is the Lorax going to find a body among the Truffula trees? Or is The Cat in the Hat more like Mrs. Doubtfire. Is this a story about the children’s estranged father finding a way back into their lives. (I’d watch that movie if Dave Eggers adapted it.)

Here’s what we absolutely know: The Man in the Cat in the Hat Suit is a good dude. He cleans up after himself. He’s great with kids. His caregiving style is unorthodox, but he teaches lessons and brings the fun. Even if he is a human in a weird dandy suit, I say we give him the benefit of the doubt. Let’s just stop pretending he’s a cat.